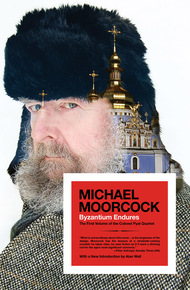

Michael Moorcock is among the most influential British authors of fantasy, science fiction, and mainstream literature. His many novels include the Elric series, the Cornelius Quartet, Gloriana, Mother London, and King of the City. Moorcock has received the Nebula, World Fantasy, and British Science Fiction awards and is a Grand Master of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. As editor of the science-fiction magazine New Worlds, Moorcock was one of the progenitors of the experimental and controversial new-wave literary science-fiction movement. His nonfiction has appeared in many UK outlets, including the Guardian, Daily Telegraph, and New Statesman. A member of the progressive rock band Hawkwind, Moorcock received a platinum disc for the album Warrior on the Edge of Time.

Meet Maxim Arturovitch Pyatnitski, also known as Pyat. Tsarist rebel, Nazi thug, continental conman, and reactionary counterspy: the dark and dangerous anti-hero of Michael Moorcock's most controversial work.

Published in 1981 to great critical acclaim—then condemned to the shadows and unavailable in the U.S. for thirty years—Byzantium Endures, the first of the Pyat Quartet, is not a book for the faint-hearted. It's the story of a cocaine addict, sexual adventurer, and obsessive anti-Semite whose epic journey from Leningrad to London connects him with scoundrels and heroes from Trotsky to Makhno, and whose career echoes that of the 20th century's descent into Fascism and total war. This authoritative U.S. edition presents the author's final cut, restoring previously forbidden passages and deleted scenes.

"What is extraordinary about this novel…is the largeness of the design. Moorcock has the bravura of a nineteeth-century novelist: he takes risks, he uses fiction as if it were a divining rod for the age's most significant concerns. Here, in Byzantium Endures, he has taken possession of the early twentieth century, of a strange, dead civilization and recast them in a form which is highly charged without ceasing to be credible."

– Peter Ackroyd, Sunday Times"A tour de force, and an extraordinary one. Mr. Moorcock has created in Pyatnitski a wholly sympathetic and highly complicated rogue… There is much vigorous action here, along with a depth and an intellectuality, and humor and color and wit as well." —The New Yorker

"Clearly the foundation on which a gigantic literary edifice will, in due course, be erected. While others build fictional molehills, Mr. Moorcock makes plans for great shimmering pyramids. But the footings of this particular edifice are intriguing and audacious enough to leave one hungry for more."

– John Naughton, ListenerONE

I AM A CHILD of my century and as old as the century. I was born in 1900, on 1 January, in South Russia: the ancient true Russia from which the whole of our great Slavic culture sprang. Of course it is no longer called Russia, just as the calendar itselfhas been altered to comply with Anglo-Saxon notions. By modern reckoning I was therefore born in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic on 14 January. We live in a world where many kinds of regression dignify themselves with the mantle of progress.

I am not, as is frequently suggested by the illiterates amongst whom I am forced to live, Jewish. The great Cossack hawk’s beak is frequently mistaken in the West for the carrion bill of the vulture.

I am not a fool. I know my own Slavic blood. It roars in my veins; it pounds as the elemental rivers of my fatherland pound, forever longing to be reconciled with our holy and mysterious soil. My blood belongs to Russia as much as the Don, the Volga, and the Dnieper belong. My blood still hears the call of our vast, timeless steppe under whose solitudinous skies aristocrat and peasant, merchant and worker, were dwarfed and understood how little material prosperity mattered; that they were united by God and were part of His inevitable pattern. Alien Western ideas came to threaten this understanding. It was in the factory towns, where chimneys crowded to shut out our incomparable Russian light, where people were denied the shelter and confirmation of God’s wide roof, God’s cool and merciful eye, where the synagogues sprouted, that Russians began to elevate themselves and challenge God’s will, as even the Tsar would not dare; as even Rasputin, playing Baptist to Lenin’s Antichrist and spreading rot from within, would not dare. Influenced by Jewish socialists in Kharkov, Nikolaieff, Odessa and Kiev, these stokers and these riveters first denied the Lord Himself. Then they denied their blood. And then they denied their souls: their Russian souls. And if I cannot deny my soul after fifty years of exile, how then can I be Jewish? Some Peter? Some Judas? I think not.

Admittedly, I was not always religious. I have come to the Greek Orthodox religion relatively late and perhaps that is why I value it so, as those persecuted millions in the so-called Soviet Union value it, worshiping with a fervour unknown anywhere else in the Christian world. I have suffered racial insinuations all my life and for these I blame my father who deserted his faith as casually as he deserted his family. Since I was a child in Tsaritsyn I have known this suffering and it became worse when my mother (by then probably a widow) moved us back to Kiev after the pogrom. My mother was Polish, but from a family long settled in Ukraine. She told me that my father had been a descendant of the Zaporizhian Cossacks who had for centuries defended the Slavic people against the Orient and who had resisted foreign imperialism from the West. My father had picked up radical ideas first as a clerk in Kharkov, later during his military service. When he left the army he remained in St Petersburg for two years before getting into trouble with the authorities and being deported to Tsaritsyn. Many of these names are probably unfamiliar to the modern reader. St Petersburg was renamed into Russian Pyotr-grad (Petrograd) in 1916, when we wanted no echoes of Germany in our capital. Now it is called Leningrad. Doubtless they intend to change it with every fresh political fad. Tsaritsyn became Stalin-grad and then Volgograd as the past was revised for the umpteenth time, and the inevitable future and the impermanent present re-proclaimed in fresher slogans, sufficient to make schizophrenics of the sanest citizens. Tsaritsyn is probably called something else by now. Nobody knows: least of all those émigré Ukrainian nationalists whom I sometimes speak to after Church services. They have become as ignorant as everyone else living here. It is hard for me to find equals. I am a well-educated man who received Higher Education in St Petersburg. Yet what good is education in this country, unless you are part of the Old Boy Network, or a homosexual in the Central Office of Information or the BBC, or Princess Margaret’s lover, like so many self-styled intellectuals who come over here and betray themselves for the peasants which, in reality, they probably are? It is incredible how easily these Czechs, Poles, Bulgarians and Yugoslavs manage to pass themselves off as academics and artists. I see their names all the time: on books in the library, in the title credits of sex-films. I would not lower myself. And as for the girls, they are all whores who have found richer prey in the West. I see two of them almost every day when I buy my bread in the Lithuanian’s shop. They flaunt their long blonde hair, their wide, painted mouths, their flashy clothes: their skins are thick with make-up and they stink of perfume. They are always gabbling away in Czech. They come into my premises for fur capes and silk petticoats and I refuse to serve them. They laugh at me. ‘The old Jew thinks we’re Russians,’ they say. Ah, if they were. Good Russians would have a discount. The girls speak Russian, of course, but they are obviously Czechs. Believe me, I know I bring these suspicions on myself, because I cannot give anyone, not even the British authorities, my real name. My father changed his name a dozen times during his revolutionary days. For different reasons, I also had to take other names. I still have relatives in Russia and it would not be fair to them to use their title since we had very strong aristocratic connections on both sides of the family. We all know what the Bolsheviks think of aristocrats.

They are of a type, you see, these girls. Ruined by Communism well before they come to the West. Without morals. It is a joke the Czechs tell: the Communists abolished prostitution by making every woman a whore. I remember girls just like them, from good families, speaking French. Fifty years ago they were crawling across the boards of the abandoned Fisch château near Alexandria while shells whistled everywhere in the dark and half the city was in flames. They were filthy and naked, luxuriating in the expensive furs Hrihorieff’s bandits had given them. Some were not more than fourteen or fifteen years old. Their little breasts hanging down, their brazen mouths open to receive us, they were utterly corrupted and it was obvious that they were relishing it. I felt nauseated and fled the scene, risking my life, and I still feel sick when I remember it. But are the girls to blame? Then, no. Today, in the free world, I say ‘Yes, they are.’ For here they have a choice. And they represent Slavic womanhood, for so long pure, feminine, maternal. But this is what happens when religion is denied.

My mother, although of Polish extraction, was attracted more to the Greek than the Roman in her religious preferences, though I never knew her to attend formal services. She observed all the Orthodox holidays. I do not remember ikons (though she doubtless possessed them). She always had a picture of my father (in his uniform) in an alcove, with candles burning. It was here that my mother prayed. She never criticised my father, but she was anxious to remind me of how he had gone astray. He had denied God. An atheist, he had been involved in the uprisings of 1905. During this period he had almost certainly been killed, though the circumstances were never entirely clear. My mother herself would become vague when the subject was raised. My own memory is a confused one. I recall a sense of terror, of hiding, I think, under some stairs.