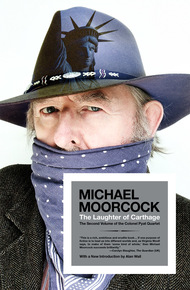

Michael Moorcock is among the most influential British authors of fantasy, science fiction, and mainstream literature. His many novels include the Elric series, the Cornelius Quartet, Gloriana, Mother London, and King of the City. Moorcock has received the Nebula, World Fantasy, and British Science Fiction awards and is a Grand Master of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. As editor of the science-fiction magazine New Worlds, Moorcock was one of the progenitors of the experimental and controversial new-wave literary science-fiction movement. His nonfiction has appeared in many UK outlets, including the Guardian, Daily Telegraph, and New Statesman. A member of the progressive rock band Hawkwind, Moorcock received a platinum disc for the album Warrior on the Edge of Time.

Maxim Arturovitch Pyatnitski, that charming but despicable mythomaniac who first appeared in Byzantium Endures, is back. Having fled Bolshevik Russia in late 1919, Pyat's progress is a series of leaps from crisis to crisis, as he begins affairs with a Baroness and a Greek prostitute while undertaking schemes to build flying machines in Europe and the United States. His devotion to flamboyantly racist, particularly anti-Semitic doctrines—like his devotion to cocaine—remains unabated, and he both sings the praises of Mussolini and lectures across America for the Ku Klux Klan. (His best kept secret is of course, the fact that he is Jewish.) As the novel ends, Pyat is in Hollywood—his new Byzantium—hobnobbing with movie stars and dreaming of making films like those of his hero, D.W. Griffith.

"The Laughter of Carthage and its companion volumes will be seen…as an imaginative record of our own time rather than as a simple reconstruction of that which has gone."

– Peter Ackroyd, The Sunday Times"The Laughter of Carthage is a formidable work in which science and technology are subordinated to narrative techniques not usually found in popular fiction...a work of grand design...cast as Pyatnitski's memoirs of a life uprooted by the Russian Revolution. He brags of his exploits as a Don Cossack; he claims pure Russian blood and a batch of patents for airplanes and automobiles. But one can never be sure that anything Pyatnitski says is true. He is certainly an egomaniac and very likely mad; he is also a reactionary Tom Swift, an anti-Semite, a sybarite and a paranoiac with a gargantuan appetite for cocaine. Rabid anti-Semitism is his way of denying the past and advancing his career as scientist and gentleman. There is also ample indication of a thin line between deceit and self-delusion. Pyat's first stop on his flight from Bolshevism is Istanbul, a teeming cosmopolis of thieves and whores but also a site idealized as the bastion of a once glorious Christendom. From there, the grotesque innocent moves west through Rome, Paris, New York City and Hollywood. Moorcock takes large risks...there are rewarding detours: lush descriptions of landscapes and the world's great cities, and a parade of characters that would feel at home in the novels of Dickens, Nabokov and Henry Miller."

– TIMEI AM ONE of the great inventors of my age. Rejected by its birthplace, my genius would otherwise be universally acknowledged; even by Turks. The Rio Cruz, loaded with snow and refugees, steamed from Odessa, heading for Sebastopol and the Caucasus. I was toasted by the British as a Russian Prometheus. How could I have guessed the irony? I was sublimely ignorant of my personal future. In those last days of 1919, having escaped an humiliating death, I became freshly inspired with my mission: I would bring scientific enlightenment to the world at large. (Now, chained, I still await my Hercules. Es war nicht meine Schuld.)

Within a day of my boarding, Mr Thompson, Chief Engineer of the Rio Cruz and by nature of his calling a cosmopolitan, a reader of learned journals, was my unqualified admirer. ‘You must get to England as soon as you can,’ he begged. ‘So many have been killed. They need trained people more than ever.’ Several other officers were equally encouraging. They were good-hearted fellows, spontaneous and sincere. The best type of Englishman; now extinct.

Until such time as, we were fond of saying, Russia came to her senses, England was the obvious country in which to further my career. Mr Green, my Uncle Semyon’s business partner, had returned to London at the outbreak of the Revolution. He would have money for me. Moreover, the support I discovered aboard the Rio Cruz suggested I should rapidly secure an important government position once ashore in ‘Blighty’.

By dint of these prospects, together with a little cocaine and wine, I was at least partially able to forget my earlier disappointments. Russia was harder to put behind me than I had anticipated and it would be three weeks before we actually reached Constantinople. Immediately we were out of sight of land, high winds and seas attacked us. A good sailor, I nonetheless felt a moderate amount of nausea and periodically was infected with a terrible, debilitating gloom. At these times I would be forced to rush from whatever company I was in to return to my bunk where for half-an-hour or so my whole body would shake, as if in time to the vibrations of the ship. These bouts were quite as much a physical as a psychological reaction to events of the previous two years, but whenever they seized me I would be overwhelmed by an agonising longing for a more innocent past, for my golden Odessa summer of 1914 when the whole world had appeared to open herself for me. In my quasi-delirium it seemed the noble city of Odysseus was lost forever to the Tartar, the Mussulman, the Jew. In conquering Odessa they had captured something of my being and still held it. Trotski and Lenin leered gigantically and grinned: with bloody fingers they brandished that small, pulsing fragment of my soul. The elements wailed around the ship in massive chorus as I wept for Esmé, my little angel, whose blonde Slavic beauty represented everything true and honest in Russia. Dishonoured by anarchists, by Mongol riff-raff, my lost sweetheart could never be redeemed. She had mocked me for my horror at her stories of rape and abasement. Esmé, my greatest support after my mother, had been my muse, my hope. If she still lived she was nothing but a Bolshevik’s whore. Esmé, as my body shuddered on its narrow bunk, I yearned to flee backwards in Time to rescue you. How different both our lives would have been if we had escaped together. I should have been loyal to you. Kà bus göruyorum. I am still, even in this decrepit body, loyal to you. For all that you betrayed me I bear you no ill will.

Before heading for Constantinople the Rio Cruz would call at several Black Sea ports, taking on passengers, disembarking troops and munitions. John Monier-Williams, her captain, was a grey, stocky Welshman with one side of his face badly scarred by an old fire. Though always polite to us, he plainly had some distaste for this commission, the last before he retired. Until now his experience had been with the Indonesian, Indian and Chinese colonies and to him our Civil War was an obscure local conflict unworthy of British involvement. A cargo-carrier converted to a troop-transport, the ship was not really suitable for passengers. Her cabins were mainly communal dormitories segregating men from women and children. Though Mrs Cornelius and myself had a private cabin, the necessary pretence of being husband and wife created unexpected discomforts for me, particularly at night, since she remained true to her Frenchman while I burned with lust in the bunk above. Mrs Cornelius was a wonderfully voluptuous woman. At that age (her early twenties) she was in her prime. It was impossible for me to put her soft pink flesh and erotic smell out of my thoughts. From time to time in her sleep she would interrupt her own delicious snores by murmuring and smacking those full, sensual lips, amplifying my desire and causing me to nurse both my homesickness and my poor, swollen penis for hours on end as the ship waded through dark, heavy seas, creaking, sighing and occasionally giving off mysterious coughing sounds, like an overburdened camel.

The other passengers were predominantly Ukrainians of the merchant class; nouveaux riches for whom I had little patience. When they were not merely dull the women were self-conscious snobs, the men complacent bores and their children and servants odious. Most pretended to noble birth; all constantly bemoaned the loss of ‘everything’ and all seemed to have carried at least two fur coats and three diamond necklaces aboard. They were war-profiteers fleeing the vengeance of the Bolsheviks, and a large percentage were Jews. I had vetted many such during my days in the Intelligence Corps and could smell them out. One or two must certainly have recognised me and initiated the malicious rumours which soon circulated: I was a Red spy, a German official or even, ironically, a Jew. I became aware of passengers who were either embarrassed in my presence or else obsequiously pleasant. My response was to avoid them. Happily, Mrs Cornelius and I did not have to mix with them much. We were invited from the start to eat at the small table set aside for Mr Thompson and most of the other ship’s officers who, because of the crowded conditions, were no longer in possession of their own messroom. Starved of English, Mrs Cornelius gladly accepted. They in turn enjoyed her humour. Their company was far more intelligent and agreeable to me than that of my own countrymen so I too was pleased with the arrangement.

We steamed on through white ectoplasmic haze, through blizzards and troubled water and, because we had not yet left Russia behind us, I was still subject to painful extremes of mood. Sebastopol, Yalta and other ports lay ahead. I was of course free to disembark at any of them and I was troubled by this. It would have been healthier if my attachment had been severed at a stroke. However, I did not much look forward to reaching Constantinople, which I understood was crammed with Russians unable to get exit visas to more hospitable countries. I consoled myself. After a few days at most in the Ottoman capital I would be on my way to London. Meanwhile I did all I could to drive the memories of Kiev and Odessa from my mind, to forget Esmé and my first flight over the Babi Gorge, the cheers of fellow-students at my matriculation speech, the delightful months spent with Kolya in St Petersburg’s bohemian nightclubs. I made an effort to concentrate on the Future, on my practical visions for building a technological Utopia. My thirst for knowledge and creative impulses were to some degree satisfied in the company of Mr Thompson, who helped me gain an intimate knowledge of the ship.

The Rio CruZs old-fashioned reciprocating engines aroused in Mr Thompson, more used to modern turbines, a certain admiration as well as suspicion. He found it marvellous they worked at all. They had been operated for years by dagoes, he said. Dagoes were notorious for hammering a ship to death. Normal maintenance procedures were anathema to them. ‘They treat their machinery the same as their horses, flogging them on until they die in their traces.’ Moving through the dark, pounding innards of the ship, his red face and hair glowing and his sharp nose quivering with puritanical dismay, he would point out his repairs and improvements, gesture accusingly at stains and dents on the brasswork, at rust and patches on pistons and pipes. The engine-room was miasmic with hot oil. Coal-smoke drifted from the stokehold. In the writhing half-light I imagined rivets bouncing in loose plates and rods shaking free of their rotating arms. Mr Thompson had insisted, he said, on the whole area being washed from top to bottom, every cog cleaned and lubricated, before he had allowed this prize of war to put to sea again, yet one never left without a patina of grime. Mr Thompson thought it would always be a problem on any ship, no matter how sophisticated her ventilation systems, so I described my ideas for a ship needing neither coal nor oil, her engines powered by two gigantic wind-vanes standing like funnels above the vessel’s superstructure and thus requiring merely an auxiliary motor and a small tank of diesel fuel. He was sceptical until I sketched the device for him, whereupon he became excited. He insisted gravely on my patenting these plans the moment I reached London. I assured him that this was my intention. At dinner that night he begged me to describe again the invention to his brother officers. They, too, were impressed. Captain Monier-Williams, who had served on sailing vessels, said he would appreciate my engine’s silence. He missed the tranquillity which used to fall over a great clipper-ship, even when she was racing at considerable speed.

Mrs Cornelius grinned. ‘I never ‘ad no bloody sense o’ tranquillity from wind,’ she said and burst into laughter shared by all except myself and the captain. Later she would explain the pun to me. Then, however, she had succeeded in her object and destroyed the over-serious tone of the conversation. After pudding, most passengers left the saloon; when Captain Monier-Williams with one or two others went to attend to their normal duties Mrs Cornelius performed some of her turns. Her career had begun in the Stepney music-halls and she had a large popular repertoire. The sailors were visibly cheered by what were evidently familiar favourites although the songs were mostly new to me. Eventually I learned them all and on more than one occasion would escape trouble, proving myself British with a rendering of Lily of Laguna or At Trinity Church I Met Me Doom.