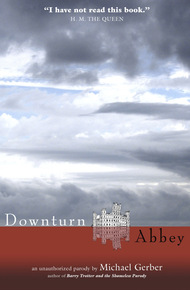

Michael Gerber has sold 1.25 million books in 25 different countries; his Barry Trotter and the Shameless Parody reached #2 on The London Times bestseller list and helped introduce Europe to American-style longform print parody. Before writing novels, Gerber contributed to The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, NPR and TV's "Saturday Night Live." His is currently overseeing the launch of a new national humor magazine/network.

Is there anything better than watching the first two seasons of Downton Abbey?...But since you've already done that, you might as well read this parody. Scheming lady's maids, butlers with secret pasts, incompetent estate management, a lovely Lady with a Turk-killing hoo-ha—Downturn Abbey has it all, told from the perspective of a malnourished local orphan being employed as a piece of furniture. Whether you're a dedicated fan of the show, or just love heavily idealized melodrama about England's Age of Exploitation, Downturn Abbey is for you, guv'nor.

The Dowager Countess will not be amused by this sharp parody, penned by a comedy genius, but we definitely were. – Geoffrey Golden, The Devastator

"Michael Gerber is a splendid and rare talent... Downturn Abbey is all of a loopy, larky and lusty delight. Enjoy!"

–Brian McConnachieThe Heartbreak of Male Heir Loss.

(April 15, 1912-June 1912)

I well remember my first day at Downturn Abbey. It was the morning after "the big canoe went down." Not what I took much notice of that—no one related to me was on the Titanic. In fact, no one related to me was anywhere. Back in those days, parents were a luxury, like protein, and I had neither. That's why I showed up at the back door of Downturn, my one shoe shined, my hair combed, ready to begin a new life.

At eight, I was a bit of slacker, but a natural impulse to better myself and avoid the considerable inconvenience of starvation had impelled me to the classified section of The Urchin magazine. Under a quiz called "Fifty Forelock-Tugging Ways to Drive Your Betters WILD," I spied a small advert for a "tray-boy" at the crumbling, half-wild estate just up the road from Ripping Foundling Home.

"Do you dream of a better life?

Travel? Excitement? Adventure?

Good luck to you. In the meantime, we require a tray-boy.

Long hours, little pay. Must be alarmingly small for age.

Full set of fingers required; mutes preferred.

Apply to Mr. Cussin,

Downturn Abbey."

As my eyes played over the tiny print, my calorie-starved faculties sputtered out a glorious future. First I'd obtain a left shoe. Then I'd rise up through the ranks, eating exotic, nutritious things like carrots, and rubbing shoulders with the great personages of the era...And then, perhaps, one of those personages would see something in me, a spark, something that recalled themselves at my age, and my chance would come. A chance to make good; a chance to show the world what I, Percival P. Percival, was put on this good green Earth to do.

For those of you unfamiliar with the workings of a great house—and in the case of Downturn, I use the term loosely; just how loosely you're about to find out—a tray-boy is a young male of approximately waist-height who follows members of the household, wearing a metal sideboard supported by his shoulders and crown. He is, for want of a better term, a sort of mobile end-table, and as human furniture, occupies the absolute bottom of the pecking order. But all work is honorable—so The Urchin serials had told me—and I was determined to be the best tray-boy Downturn had ever had.

"You'll be back before nightfall," predicted the Home's Matron, as fat as all of us were thin. "Say hello to Colin for us, will yeh? If he's still breathin'."

This was not idle speculation. Colin, an older, bigger boy and Matron's favorite, had for some years been employed holding up Downturn's subsiding North Gallery. Fortunately, Tray-boy is not as physically demanding a position as Foundation-lad, and offers much contact with the family. But this can be a disadvantage, if one cannot show discretion. These articles are, I suppose, a response to that—a clearing of the mental mechanism after eight years spent observing the most incredible things in silence. To be all of thirteen, for example, and see Lady Marry dance Le Sacre du Printemps in the altogether—I don't mind telling you, I nearly burst a blood vessel. And stroke was not the only peril; I later found out that the boy I was replacing, a chap roughly equidistant between Colin and myself, had succumbed to ether fumes while helping the Earl of Cantswim anaesthetize some butterflies. But I didn't know that then. Lucky for me, I didn't know anything. When I rounded the path and saw the estate for the first time, I was sure that great things were ahead.

• • •

I was met at the back door by Mr. Cussin, Downturn's fearsome butler. "You must be the new tray-boy. Come in." Something about the bright Spring morning must have offended him, because Mr. Cussin then uttered a string of words so foul that I assumed only orphans knew them. At first, I was frightened by the oaths and imprecations that constantly issued sotto voce from the man as he navigated a world that did not come up to his standards. Later, I learned it was a habit over which he had no control, any more than Mrs. Snughes could prevent falling asleep, or Craisy, Downturn's dogsbody, could stop herself from setting fires.

"Not the drapes, Craisy!" Mr. Cussin barked. "The fireplaces!"

"Sorry, Mr. Cussin."

"Never mind that. This is Percy, our new tray-boy."

"Pleased to meet you," she said. "It'll be nice to finally have someone underneath me."

"You go, girl," a passing housemaid cracked. Craisy blushed crimson, and skittered away.

"Nice talk," a slick-haired footman said as he streaked by with a gleaming silver salver. "Farm-girls only have one thing on their minds."

"Except when it comes to you, Dhumbas," said another housemaid.

"Dhumbas, don't forget the bicarbonate of soda for the table." Mr. Cussin pounded his burning sternum. "Cook is in fine form this morning."

Another footman approached; in his wide Yorkshire palm were two small blue objects. "Mr. Cussin, her ladyship asked me to put out these salt-and-peppers instead of the silver ones. I think it's some American custom."

"Oh Lord." The butler regarded the pair of ceramic hats with unbridled distaste. "Who or what are the Chicago Cubs?"

The footman shrugged—then noticed me. "New tray-boy? Welcome to Downturn." We shook hands.

"A word of advice: never try to carry one of Cook's soufflés on your own; the last fellow got crushed flat. Or was he the one that got burned up? No, he suffocated! Anyway, we go through tray-boys at a terrific rate."

Anything I might say seemed likely to reveal the terror newly blossoming in my bowels, so I just smiled.

"Oh, I'm only chaffing you...You hope." Smiling, Killem turned to Mr. Cussin. "Doesn't talk much, does he?"

"If only the same could be said for the rest of you..." The butler handed back the little hats. "Put them out, Killem, monstrous as they might be." The footman walked away briskly, and Mr. Cussin sighed to no one in particular. "Yanks."