Raymond Bolton lives near Portland, Oregon with his wife, Toni, and their cats, Max and Arthur. You may follow him on his FaceBook author page, as well as on Twitter, and on Instagram.

Everyone who touches you transforms you, if only a little. But if you enter their minds and think what they have thought, even do what they have done…how complete will that transformation be?

If Peniff had been born an ordinary man, his family would be safe—safe as anyone can be in a land torn apart by war. It is his singular gift, however, that causes his wife and children to be imprisoned and held hostage and him to be used as a tool.

Caught up in a struggle between opposing warlords and refusing to play the game, Peniff elects to take the moral high road. This is the story of a man, in all other ways ordinary, rising above his fears to do what he must.

Can he free his family before his betrayal comes to light? Moreover, what will he become before his journey is over?

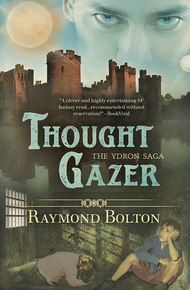

Thought Gazer, the second volume of The Ydron Saga, is the first book of the prequel trilogy to Awakening.

"Bolton breathes originality into the genre with his singular focus on telepathy."

– Stephan J Meyers, author/illustrator"A clever and highly entertaining SF fantasy read, Thought Gazer takes The Ydron Saga to another level and is recommended without reservation!"

– BookViralBedistai Alongquith squatted beneath the dripping boughs of a falo'an tree. Its massive trunk and outstretched limbs had provided shelter from the storm. So large was this specimen, it is doubtful any force of nature could have moved it. Indeed, hollowed out, it would have been nearly as commodious as his home. Protected so from the full force of the wind, Bedistai had waited out the tempest's passing. As he nestled among the roots of this venerable old giant, he quietly chewed a moa root. Its mild narcotic properties kept away any cold, hunger or thirst during the nearly two days he was forced to remain in this posture and it prevented his muscles from cramping, despite such prolonged immobility. Now he began the ritual deep breathing exercises he had learned long ago. These would gradually restore normalcy to his metabolism and circulation to his limbs. To move before he had completed these efforts and restored himself surely would have resulted in strain or injury, so, with the practiced patience of a hunter, he breathed and offered the required prayers of thanks, meticulously following the twenty-one Acts of Renewal his people, the Haroun, had observed for untold generations.

This was not the first time he had performed the Acts. The hunt always took him far from home and for extended periods. A tent or shelter-cloth would have added unnecessarily to his endath's load, and a fine hunting endath was far too valuable to squander as a mere beast of burden. If the creature were to carry him across rough terrain in quick pursuit of quarry, it needed all its reserves at any given moment. So, out of respect for the one on whom he had depended for so much and so often, he brought only those things he could not do without: the clothes on his back, his weapons and tools of the hunt, medicine for treating injuries, a water skin, salt for curing meat and some starter for his bread whenever he could trade for flour.

Bedistai, in fact, was not given to any form of excess. Even his appearance belied his talents. Most hunters of his ilk wore the talons, fangs, quills and pelts of dozens of successful takedowns. His clothes, on the other hand, were of simple sandiath skin. Except for a solitary tooth suspended from a cord around his throat, he wore none of the ostentation of his calling. The significance of the tooth was that the creature who bore it, a beyaless cath'en, had killed all but one of a fullyarmed hunting party numbering a dozen. Bedistai, the sole survivor of the attack, had managed to slay the cath'en. It had been his first hunt, and while the accomplishment had elevated him in the eyes of his peers to master hunter, the tooth served more as a reminder than as a boast.

Aware that her rider had begun to stir, the endath approached. Her smooth muscular body moved with a grace that strongly suggested her true speed and power. The muscles of her four legs, of her long graceful neck and tail, as well as her powerful loins, all twitched with anticipation.

As the ritual concluded, Bedistai stretched and flexed his back, breathing deeply with each tentative motion. Eventually he turned his head to greet her and smiled at the streamer of steam the wind carried off from her solitary nostril. She, like all of her kind, had an extremely high body temperature brought about by an incredibly fast metabolism. Bedistai had grown accustomed to the fact she never seemed to sleep. He had learned through careful observation during their long association she slept quite often—several times an hour—but only for instants. He even suspected she dozed mid-stride, but she never stumbled or hesitated, if in fact she did. Hers was an odd biological cycle, duplicated nowhere else, and it served both to protect her from predators and render her a perpetually alert, perpetually rested companion.

He arose from his haunches and stretched his arms and legs. He was hungry. The storm that had passed had made hunting impossible and he had not eaten during all of the time he had spent here.

"Come, Chawah," he beckoned. "Let us find breakfast."

The endath tossed her head and flicked her tail at the sound of his voice. Then she did the thing he loved most, the thing no other of her kind ever did. She met his eyes with hers. Her clear gaze fixed upon him and the living spirit inhabiting that magnificent body reached out to meet him. Bedistai wished she could speak. He strode up to her and rubbed her neck with strong affectionate strokes while he spoke to her in soft soothing tones. Only after he had examined her body and assured himself all was well, did he place the saddle upon her and secure his few arms and possessions behind it. He hesitated for an instant before mounting, listening for sounds on the wind. Then, with no visible effort, he leapt onto her back and took up her reins. His seat touched and she took off as though their will were one.

The Expanse of No'eth is not flat as are the plains of Rian or Dethen. It undulates in a series of rises and falls so that quarry a short distance from pursuit finds easy concealment. Sound does not carry well and the thickets that erupt in the lee of the many hillocks serve as further cover. Scent is as likely to reveal the upwind presence of hunter to prey as the reverse, so only by disciplined scrutiny of the details of the terrain and disturbances of the brush and grasses would Bedistai find success.

The rains had washed away all but the freshest tracks, and those impressions he encountered were clear and easy to read in the soft wet soil. Although he was looking for the spoor of a jennet or umpall—both large swift herbivores—this morning he would have settled for a rodent such as a marmath. Skewered, it would make a fine breakfast and his stomach rumbled at the thought.

Several times he dismounted to examine evidence of some creature's passing. Each time, however, he was forced to return to his endath's back with no useful information gained. The occasional broken branch or crushed shrub indicated the damage had occurred several days earlier. The stems were dried at the break and the leaves were browning at the torn edges. Then, as he came over a crest, he spied the fresh and unmistakable impressions of an umpall's cloven hooves. They were clear and evenly spaced. This beast was in no hurry and Bedistai knew if he proceeded with care, he could soon overtake it. He maneuvered to remain downwind from the trail and below the concealing ridge lines. Several times he had to backtrack because the creature's unpredictable wanderings took it down a different ravine from the one he had expected. Due to the endath's smooth gait, however, Chawah's footfalls were almost inaudible and lost time was easily made up without revealing their presence.

Chawah turned her head into the wind and a quiver ran through her loins. The gust struck Bedistai and he smiled. It was rich with umpall scent. With a gentle tug on the reins, he slowed the pursuit. Now, instead of paralleling the quarry's trail, they followed it. The soil held deep impressions and the matted foliage made a path any child could follow. Still unable to see the beast, but hearing its snort, Bedistai slipped to the ground, bow in hand. He released the reins and gestured to her to remain where she was. Drawing an arrow from the quiver, he fitted it to the string. He had nearly circled the mound separating him from his prey and was about to skirt a clump of brush, when he heard muffled hoof beats just ahead. The wind in his ears had nearly masked them, but he recognized them for what they were.

Raising and tensioning the bow, he stepped into the open. The beast turned to face him as he emerged. Its ears were up and its nostrils flared as it sensed the danger. In that seemingly long pause between the creature's perception and its reaction, Bedistai drew the bowstring, bringing the arrow's flights to his ear. As he took a slow, deliberate breath, his fingers released…

He never saw the arrow reach its mark because, in that very instant, Chawah's panicked cry filled his ears and snapped his head around. The sound tore at him. Without thinking, he scrambled toward her as fast as he could. Clasping his bow, both arms pumping, he ran with all his might. She cried out again and he drove his feet harder into the ground, digging for every extra bit of speed he could muster, cursing each time he slipped. Without thought for his own safety, he burst into the clearing where he had left her.

No'eth is an empty land with sparsely scattered villages, so Bedistai was startled by the sight of four strangers swarming around his companion and clutching at her reins. Chawah's eyes were wide with fear. Finding nowhere to retreat, she tried to rear onto her haunches, but the youngest intruder had thrown a rope around her neck. When she rose onto her hind legs, he hung with his entire weight. Her fragile neck could not support him so, bellowing in pain, she lowered her head and dropped back onto her forefeet.

"Release her!" shouted Bedistai. "Move away from her now!"

The four turned to face him. The nearest one, startled at first, smiled and reached for the sword slung from his hip. Bedistai dropped the bow and reached for the knife at his own. With a sweeping underhand toss, he delivered it squarely into the man's belly. The stranger dropped his weapon, eyes wide with surprise. Grasping for the haft, he took two halting steps forward and fell face first onto the soil.

Bedistai leapt over the fallen figure towards the young man with the rope. The youth's nearest companion, also armed with a sword, drew it and moved to interpose himself between the two. As the hunter came within reach, the swordsman swung. Bedistai ducked beneath the arc of the blade and heard the metal resonate as it clove the air above his head. Before the blade could finish its swing, Bedistai closed in on his attacker. He captured his opponent's sword hand with his right and punched hard with his left until he heard ribs crack, then punched some more. When the man would not release his grip, Bedistai pivoted, and with both hands brought the man's forearm down upon his knee. The weapon fell to the ground and Bedistai drove his left elbow up, into the man's face, retiring him.

Out of the corner of his eye, Bedistai saw a flash of color hurtling towards him. He dodged, but not quickly enough, and he doubled over in pain. Enveloped in rage, he opened his mouth and a roar rose from deep within. One hand went to his side and he felt the warm wetness of his own blood. He pulled a pointed shaft from his side and kicked hard at the cause of his indignation.

The man, spear in hand, dropped to his knees, mouth agape, all breath gone from him. Bedistai, bent in agony from the effort, straightened and took a step forward. Tearing the spear from the man's grasp, he turned it end-for-end and drove it deep into his foe's abdomen. The man froze in position, twitching reflexively. Bedistai gave the shaft a twist, and when the man jerked in response, he extracted it and let the body topple.

Now there was only the lad holding the rope. While his Haroun upbringing and life on the frontier had taught Bedistai to react quickly and without mercy to danger and injustice, he was inclined to dismiss even the most foolish acts of the young. Despite the fact this one still held the neck of his friend in a noose, because of the lad's age, Bedistai considered releasing him.

"Leave her alone, boy, and go," he said. "Go back to your home."

The young man stood his ground. Not a movement nor expression on his face belied his intentions.

"Release the endath and I will let you go unharmed."

Perhaps it was the speed with which his three friends were dispatched that caused him to distrust these words, but the youth tugged the rope and began to force the endath to follow as he backed from the clearing.

"You must not do that," instructed Bedistai, pointing the spear to emphasize his earnestness. "She will not leave with you. I will not allow it."

If the youth thought his next course of action would elicit fear or hesitation, he severely miscalculated, for he made the worst and final mistake of his life. With his free hand he reached for the dagger suspended from a cord around his neck. Pulling the knife over his head he cried, "Follow me and I'll kill it!"

As the boy moved the blade towards Chawah's neck, Bedistai hurled the spear. The throw was effortless and unerring and the young man died where he stood. When he fell, he became of no further concern and Bedistai, without giving the body so much as a glance, strode deliberately towards his friend.

Chawah was visibly agitated. Trembling, she glanced nervously from side to side and her long tail thrashed violently.

Bedistai extended a hand to her and called in a slow incantation, "So, so, so, Chawah. So, so, so." The words were unimportant, only the soothing repetition and the tone of his voice.

Little by little, her breathing slowed and her manner calmed. Her eyes gradually stopped darting about the clearing, looking for danger. Eventually they settled onto Bedistai's placid familiar form. He waited until the blind panic in her eyes completely subsided before coming close enough to touch her. Before that, had her muscular tail, which was twice the diameter of his torso at its base and longer than her neck and body combined, lashed out in his direction, it could have broken his back or a limb or worse. It might have killed him. It would have been an unintentional act, but the danger was real. Bedistai considered it a small wonder she had not maimed the boy. Now, however, her eyes met his and the two connected. The meeting was palpable and he saw she felt it too. Her body relaxed and her entire posture reflected calm. Her tail settled nearly to the ground. Her neck was no longer rigid and even sagged a bit. Her breathing slowed and the pupils of her eyes gradually contracted. Only then did he begin to stroke her neck.

"Oh, Chawah. They are gone, now. No harm. They are gone and you are safe."

She looked into his eyes, and after examining his countenance, gently brushed his arm with the side of her face.

"Good girl," he said and caressed her cheek with his hand.

Then, satisfied she was truly calm, he began to walk around her, his hand always on her so she would not be startled by an accidental touch. As he proceeded, he examined her for injuries. Her legs, from each tripod of toes to her shoulders and rump, bore no sign of injury. Though her chest still heaved, her breathing was regular. He could not see her back, an arm's reach above his head, but her movements gave no hint that it troubled her. Nonetheless, he would examine it later to be certain. In fact, except for the place where the noose had chafed her neck, from her heart-shaped head with its solitary nostril and great blue eyes, down the slender neck which equaled her dun colored body in length, to the tip of her long pointed tail, everything about her appeared as it should. He breathed easier. Only now would he tend to himself.

The saddle bag he wanted was beyond his reach. As often was the case, Chawah anticipated him. She reached back and, with her mouth, plucked it from the saddle and gave it to him. Inside, he found a packet of herbs that would congeal the blood. Breaking it open, he poured the contents into his palm, then flinched when he applied it to the wound. Fortunately, the effects of the moa root had not yet vanished, or else the pain would have been intolerable.

Holding the medicine in place, he returned to the nearest body. Hoping it would not be flushed away by his blood when he removed his hand, he tore two lengths of cloth from the man's clothing. One he folded into a pad to contain the remedy and absorb the blood. The other he used to bind it in place. Satisfied it was secure, he decided to investigate what had happened.

He could not discount the possibility there were others nearby, so he turned his attention to the immediate area and tried to determine how the quartet could have surprised her. Chawah would never have allowed them to approach under ordinary circumstances. His eyes went from signs of a scuffle left in the soil when they had captured her, to a rise not far from the origin of those marks. Its summit was a little higher than her head and was a likely spot for an ambush. Still, they could not have known in advance he would come to this place any more than he. So how had this occurred?

He was not about to investigate armed with only the spear, so he returned to where his first victim lie. He extricated his knife and wiped the blade on the man's tunic before returning it to its sheath. Then, he picked up the discarded bow, slung it over his shoulder, and a moment later was standing atop the knoll. On its summit, footprints, handprints and grass flattened by what was surely a prostrate form told a partial story of someone who had climbed to the top, had fallen briefly onto his belly, then scrambled to his feet and jumped. That one, likely, had landed upon the animal to be joined in the clearing by three more, one of whom had followed the first, leaping down the face, while the other two ran down its side.

But what had brought them to this remote spot in the wilderness? That was still unclear. He scanned the surrounding area, looking for anything unusual. For a while, nothing appeared out of place. A flock of chur soared overhead and a few other birds winged from tree to tree in their morning quest for food. Grasses and brush moved softly in the gentle breeze. Then he spied, protruding above the vegetation, what appeared to be a portion of a wooden structure.

He paused to examine the bandage and was pleased to see it was not saturated. The blood was no longer flowing. If he were careful, it would hold until he could sew the wound.

He turned and called, "Chawah!"

She craned her head and met his eyes.

"Stay here," he said. "I will be right back."

Her eyes half blinked in acknowledgement and Bedistai, satisfied she understood, turned and scrambled down the opposite side of the mound. He made his way down the slope and through the underbrush until he neared the place where the curious object stood.

In this wild place, anything constructed by man was suspect and he could not be certain there were no other marauders. He listened for the sounds of conversation or careless movement, but at first detected nothing. Then, as he approached, he heard soft rhythmic noises he could not identify. He slowed his approach even more, listening carefully. The sounds repeated in a pattern he could not attribute to any animal, but neither were they sounds of speech. A loud snort came from directly ahead, but it was separate from the utterings that had caught his attention. He drew his knife and peered through the brush. He saw several large hairy forms moving and heard the sound of hooves shifting stance. He circled to his right, keeping some distance between himself and whatever creatures they might be. Then, as he peered through the branches, he smiled. In a clearing stood an ox in harness and four horses saddled as steeds. The ox shifted and snorted as Bedistai emerged and the sound confirmed this was one of the noises he had heard. But now the puzzling murmuring which had drawn him here had grown clearer, coming from a place directly behind this great beast.

As he circled the ox, four wooden corner posts revealed the presence of a cart. Numerous smaller bars showed it to be a cage. Curious as to what it might contain, he approached. There, within the bars and resting on a bed of soggy straw, was a small wet pile of what appeared to be fine cloth. Well, "resting" was perhaps not the word, for the pile shifted and heaved in a pattern coinciding with the soft repetitions—too high in pitch to belong to any animal he knew. He stepped up to the cage, yet whatever was moving within the pile did not react to his presence. Carefully, he extended an arm through the bars, far enough to reach the mound of fabric. He grasped a fold between his fingers and tugged. At once, the pile rose up and he stepped back, pointing his knife. He found himself face to face with a woman whom, under other circumstances, he might consider beautiful. She was sobbing and trembling and, from her pallor, he could see she was deathly ill.