Deb Taber is a writer and editor specializing in speculative fiction. She was introduced to Pierre Breton's The Secret World of Og and Norton Juster's The Phantom Tollbooth before she could fully speak, so it should come as no surprise that her inclinations to write and edit bent the way they did.

Now, she edits professionally as a freelancer for publishing houses and individual clients, lending her editorial eye to everyone from first-time novelists to best-selling authors. She is working on developing detachable eyestalks to facilitate this procedure.

When not reading others' work, she spins her own stories out of the Pacific Northwest dampness in a coffee-fueled frenzy, exploring the murky and tortuous recesses of human and inhuman nature. Her fiction has appeared in Fantasy magazine and various anthologies.

Jin brings death to set the world back into balance: a balance of population and resources, creation and destruction, choice and certainty—a balance more important to it than any individual life, including its own. Sandy, a young woman thrust violently out of her farm life into the dispassionate science of neuters like Jin, discovers her own needs for balance: safety and adventure, art and science, self-protection and love. But human life is full of change, and as the world is thrown off balance for all, each must learn to see in new ways for the survival of friends and enemies alike.

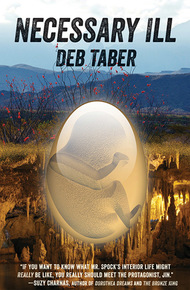

Necessary Ill by Deb Taber, selected as Library Journal's science fiction debut of the month, uniquely posits humans entirely without sex or gender. In a near-future dystopian Earth in which neuters have been literally forced underground, Jin metes out careful doses of death by engineered diseases to revive the polluted, overcrowded planet. Jin is ruthless yet compassionate; but its already-conflicted choices become even more so when it encounters Sandy, a young woman thrust violently out of her life on a farm into the dispassionate neuter society. As outside and inside worlds roil with danger, all must learn to really look at—and see—each other if they want to have a chance at restoring many delicate balances. – Athena Andreadis

"Taber's debut novel presents an all-too-credible dystopic future world and, in Jin, a complex character whose mind approaches the world and its priorities in a very different way. The characterization of truly genderless individuals—not androgynes or hermaphrodites—and the portrayal of an approach to the world that is both ruthless and compassionate make this an excellent candidate for book discussion groups and provide strong evidence for the availability of significant genre literature. Highly recommended."

– Library Journal, starred review, March 15, 2013"What Taber's surface tale resembles is a blend of James Tiptree's famous genocidal fable "The Last Flight of Doctor Ain" mashed up with Michel Faber's novel Under the Skin, in which an alien masquerading as a human female relentlessly harvest humans for food. And when you factor in Sandy's grokking-the-Other thread, elements of Le Guin's The Left Hand of Darkness or Karen Lord's The Best of All Possible Worlds seem to emerge as well. It all makes for a rich and provocative reading experience that blends the cerebral with the emotional."

– Paul di Filippo, Locus Online"Skillful pacing, unpredictable twists, nail-bitingingly tense moments, and an adroit resolution make this an unusual and engrossing addition to the post-apocalyptic genre."

– Publishers Weekly"The author speculates about how individuals and society might evolve if sex wasn't such a potent part of the human personality. Some readers may find the sometimes dispassionate discussion of mass murder a bit unsettling but no one should find fault with the prose. Not the cheeriest book I've read this year but one of the more thought provoking."

– Don D'Ammassa, Critical Mass"At its heart, Necessary Ill concerns itself with character and situation; with the social experience of marked vs. unmarked bodies, and the ethics of preservation of life. Is it better to kill many in order that the species might survive? Is it right to permit the human race to drive itself to extinction, if by one's actions one can prevent it? Is it ever possible to act ethically in taking choices away from other people? Necessary Ill doesn't answer the questions it raises, or at least not all of them. But it asks them thoughtfully, and with an eye for character that makes for an enjoyable read."

– Liz Bourke, Tor.comChapter 5

The sun quickly warms Jin's clothing and skin once it leaves the caverns. Above ground, foot travel is always enjoyable — the feeling of muscles stretching and contracting and the clarity of mind that comes with motion, making ready for the gathering of new information and the generation of new ideas. For now, there is no sack of death on its back. It is here to study and observe, to spend day after day just traveling and learning.

Raw desert gives way to shacktowns, where the poor are no longer driven off the arid lands, but instead have settled into makeshift homes pieced out of every material imaginable — broken cars, cardboard boxes, anything that can be found in the expansive landfills and pushed, dragged, or carried back to within walking distance of the rivers, streams, and rain collectors. Dying eucalyptus tree windbreaks separate the shacktowns from the blue-collar lo-loc subdivisions, complete with grocery stores, restaurants, and shopping areas. Beyond these, healthier breaks of various succulents give privacy and welcome shade to the larger estates situated far enough from the river that they must pay extra to have water shipped directly to their homes. Every home, rich or poor, has some attempt at a food garden, and this time of day a few children and older adults are out taking care of the plants, weeding and shifting canvas shades to protect the precious growing things from the sun.

There is so much the human mind knows, yet so much more to learn. In passing, Jin ghosts the people around it, not for the plague study, just to get to know them a little bit. Its stomach contracts as it ghosts the underfed shacktown children, but their synaptic firing is sharp and quick. Despite the hunger Jin feels in them, the youngest of the children are still strong and full of life. Only the pubescent ones begin to feel the effects of a lifetime of foul air and uncontainable waste, foods that are processed too much and water that is not processed enough.

In the heart of Carlsbad, everyone stays indoors, most of them crowding the long, rectangular buildings of the main water reclamation and processing facility for the area, counting the minutes left on the day shift. Others snatch a few last moments of sleep before they must awaken and prepare for a long night's work. Only a few people are out, mostly men who load and unload heavy plastic bottles from the trucks that line the streets, heating the already scorched pavement with their biofuel fumes of alcohol and animal dung. The local water business brings limited wealth, and the workers can't afford to waste their time, so they pay less attention to Jin than they do to the flies that fill the heavy air.

Jin continues north, back out into barren desert, listening to the music of the blood circling through its veins, filtering the smells that drift in from the landfills that lurk at the edges of its vision. The calluses on its feet thicken, and Jin feels them grow from inside and out. Even with all its awareness, the awareness of the entire Network, no one has yet figured out why gens can't feel inside themselves like neuts. Jin chills at the thought of not knowing its own body, not understanding where each sensation comes from. To have unknown pain, to be told of cancers eating away but not be able to locate and stop them; not to feel the heart rate increase, the white blood cells form and gather; not to be able to find infection and direct the immune system to create a cure from within… Terrifying.

Still, many neuts die in the plagues, too, and Jin understands. Spreaders infected from their own jars don't always realize the problem until too late, their minds focused on the dangers outside, not the ones they bring. But that is a risk, not the insurmountable barrier gens face between themselves and their own bodies. Jin thinks Tei may have been right. Spreading is a miserable life sometimes, but to maintain the health of the overall species, a certain amount of culling must be done. Here Jin's mind circles, step after step, as it moves toward the north, away from home.

Roswell looks empty as Jin crosses the city's southern border. The military institute fills the western half of town, while goat farms and trailer towns dominate the eastern section. Sandwiched in between, the main street of old downtown is preserved.

Jin peers into the windows in an effort to brand itself a tourist. High-priced plastic aliens stare back at it with their gaping black eyes as its ears scan the area for signs of activity. There are no street people, no poor people, no one outside without an immediate purpose. Even the tourists move from shop to shop with determination. A plague has been here recently, but something is wrong.

Jin approves of the location — spreaders must take care to hit near home sometimes or people might begin to suspect. But the Council is growing feeble-minded if it allowed a plague to take out the lower classes without a noticeable effect on others. It will have to ask Bruvec about that when it returns home; perhaps there's a balancing plague scheduled for the area, a common practice since not all delivery mechanisms can be demographic-agnostic.

In any case, the reduced population makes the area useless for a study. Bruvec was right, it needs passenger fare. Albuquerque is a long walk with limited food and money, and the area in between is almost entirely shacktowns, garbage dumps, and unshielded desert. Not the kind of place Jin needs. Not enough variety of humanity to study a city like the one it will target, the place it once called home.

Jin wanders along the main highway until it finds a screen advertising the local ride stop. Trucking companies with extra space in their cargo holds have listed their destinations and passenger fees. A pharmaceutical supply truck on the way from Dallas to Albuquerque lists a climate-controlled cargo area with cushioned seating for a reasonable fee, so Jin waits for that truck to come by.

The ride to Albuquerque should be a safe place to rest, but Jin can't relax. It never can sleep well away from home. There is too much unrest, too many people finding out the truth about neuters, or finding parts of the truth and making up the rest. It notices a crumpled flyer on the delivery truck's floor and straightens it out just to ease the boredom with something to read. The printout is from a group calling themselves "Citizens Against Generated Disease."

In the 1980s, research groups reported to the American public that AIDS was the work of hate groups targeting homosexuals and drug users. Scientists denied these claims and the researchers were silenced, but were the claims ever really disproved?

Genders could think so close to the truth, yet still get the story all wrong. As far as Jin knows, humans didn't create the HIV virus; certainly not the Network, nor any other group Jin knows. The disease wasn't a product, but in a way, was the beginning. Some people of the late twentieth century thought that the major diseases of the time were nature's way of curbing the population. One neut decided the times were desperate enough that nature ought to be helped along.

Neuters didn't know each other then, didn't have anything like the Network. One neut named Rumbauch worked alone, studying chemistry, neurology, everything it could, as most neuts naturally tend to do. With their brains free from the constant mating dance that absorbs even a celibate gender's mind, other thoughts and drives must fill the time.

Rumbauch saw that the balance between the population and the available resources for a healthy life was out of hand and getting worse by the minute. The only population control left to the public was to shoot, knife, or nuke each other, leaving the vicious in charge and the rest dead or well on their way.

So Rumbauch became the first spreader.

A few years later, Rumbauch and other neuts formed the Network as a way to coordinate their varied interests, ensuring that the slaughter was balanced by contributions to the knowledge and health of humanity as a whole, as well as research into sustainable food and water supply and waste management. The latter failed to keep up with the growth, however.