Laura J. Mixon started writing for her own amusement at age eight, and fell in love with SFF when she discovered the science fiction shelves in the local library. She's been writing and reading it ever since.

Her latest work, Up Against It, came out from Tor Books (as M. J. Locke) in 2011 and is due for a re-release soon as part of an upcoming trilogy, WAVE. The series features a group of savvy and desperate people (and other beings) who live in a populated and fractious solar system a few hundred years from now, all struggling to survive—and prevent an interplanetary war.

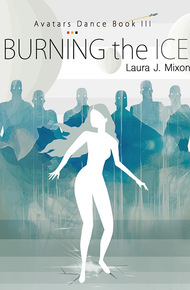

Earlier works include her acclaimed feminist cyberpunk trilogy, AVATARS DANCE (Glass Houses, Proxies, and Burning the Ice); Greenwar, an eco-thriller collaboration with SFF writer Steven Gould; and Astropilots, a YA science fiction novel chosen as the lead book for OMNI-Scholastic's TIME SHIP series. She won the Hugo Award in 2015 for best fan writer.

Mixon's work has been the focus of numerous academic studies of technology's impact on gender, identity, family, and the environment. In addition, she has a 35-year career in environmental engineering and technology, with expertise in sustainability, risk, and information management systems. In 2008, with renowned game designer Chris Crawford, Mixon co-founded Storytron, and collaborated with Crawford to create an interactive storytelling development tool for writers.

A Clarion graduate (1981), she served for two years in Kenya in the Peace Corps (1981-1983). Nowadays she can be found on Twitter as @LauraJMG, and blogs occasionally at laurajmixon.com and feralsapient.com.

More than a hundred years after a small band of humans stole an antimatter-fueled starship and headed away at interstellar speeds, a colony of the renegades' descendants are now struggling to survive on Brimstone, a barely-habitable world of ice and bitter cold four dozen light-years from Earth.

In the long run, they hope to slowly terraform Brimstone, making it, if not Earthlike, at least bearable. In the short run…well, life is hard, and most people wouldn't be eager to get away from the main colony to work on a scientific project in the howling frozen wastes. For Manda, though, it's a deliverance. Isolated and traumatized when her clone twin died at birth, she isn't cut out to get along well with others, and makes herself and everyone around her miserable.

But her self-imposed semi-exile leads her to make a world-shattering discovery that will change everything—if she can get out with the news alive. For it turns out that there are political plots and counterplots still active in the colony, dangerous twists tracing back to Earth itself...and outward to the stars.

Burning the Ice by Laura Mixon—winner of a Hugo for Fan Writing—is the youngest sibling of Avatars Dance (along with Glass Houses and Proxies), equal parts first contact and evolved cyberpunk. A small human band is struggling to survive on Brimstone, an ice moon of a gas giant. All colonists are vat-born clones in sib groups except Manda CarliPablo: she's a singleton, which makes her an outcast. Manda's discovery of intelligent life in the sea roils the colonists who intend to terraform Brimstone, thereby committing xenocide—and further danger comes from the discovery that the starship that brought them and its long-lived crew, previously thought lost, is actually lurking in orbit influencing the colony's fate. – Athena Andreadis

"Long-range sequel to Mixon's impressive Proxies (1998)….Tense, complex, and spellbinding."

– Kirkus (starred review)"The novel's real strength lies in the author's depiction of the future society, with its complex system of degrees of kinship, social obligations and controls, sexual morals, and even appropriate pronouns…The vivid storytelling and a high level of imagination mark this as perhaps Mixon's best work to date."

– Publishers Weekly (starred review)"A brilliantly conceived and executed novel, filled with technology and genuine human warmth. Mixon asks important questions here, about what it means to be human and the sacrifices we much make to retain that humanity."

– Brian Herbert, author of Dune: House Atreides"Mixon's technical knowledge is superb, and her handling of the not-quite-humans who live and die in the terraforming colonies is heartfelt and insightful. This is a not-to-be-missed novel for those who love modern science fiction."

– Frank M. Robinson, author of WaitingUr-Carli Pays a Visit

Manda ate breakfast alone in the mess, later, at one of the tables nearest the galley. None of her clone was there. It was just as well, since she was still cranky and not in the mood for company. The temperature anomaly her marine-waldo had reported had turned out to be a thermocouple malfunction. As she'd known it would be.

The young ObediahUrsulas she'd yelled at sat at one of the other tables, along with their other two vat-mates: four identical copies with the same round face, black eyes, brown, arrow-straight hair, and compact, lean build. Manda didn't need to hear their words to know they were trading insults about her.

Her lip curled. Bite me, infants. The set glanced at her with identical angry glares, and then huddled together.

Well, she thought, rueful, at least I've got entertainment value. With a piece of mana bread she mopped up the last of the gravy and vat-grown chicken from her plate, then scooped up and pocketed the rationing chits still on her tray and stood. As she did so, a low rumble shook the trays and silverware.

Manda and the others looked up. Brimstone circled its mother planet once every thirty-four and a quarter hours, and being so close to a jovian giant two and a half times the size of Jupiter meant tidal stresses produced frequent quakes. They rarely amounted to much, but several times in her life Manda could remember quakes big enough to trigger cave-ins, and a big one when she was a child had killed several people. So whenever the rumbling started she felt a prick of fear, and saw that same fear reflected on others' faces.

The quaking died away, though, and within a couple of seconds everyone had returned to what they were doing. In Manda's case, leaving.

Then ur-Carli entered. Manda stared.

The syntellect occasionally donned an avatar (a virtual projection) or a proxy (a humanoid waldo) and made an appearance, but sightings hadn't been all that common in the past few seasons. Manda hadn't seen ur-Carli at all, since it had finished helping her with the sea mapping software last summer. She pulled up on the stretchy, transparent mesh of her livehood mask and peered out fromunderneath it. Ur-Carli vanished.

The syntellect was projecting, then, rather than borrowing one of the colony's handful of still-functional proxy bodies. And none of the dozen others seated at the surrounding tables reacted to the syntellect's presence, which meant it must be projecting to Manda's liveface alone.

Ur-Carli's user interface was humanoid, a frail old lady with wispy white hair and pale skin and blue eyes: Carli D'Auber, to be exact, who had travelled here from Earth with the crêche-born, and then decided to stay with the colonists rather than head off to parts unknown. She—the real Carli—had disappeared within a couple seasons of landfall; she'd been killed, presumably, or chosen to end her very long life, out on the surface.

Manda smoothed her livemask over her face, surprised.

"What do you need?" she asked the syntellect.

One of the (few) things she liked about ur-Carli was that its auditory interface was better-designed than most of the colony's syntellectual systems; it understood spoken English relatively well. The colony's computational jack-of-all-trades, it had been around for just about forever, since even before they'd made landfall. It had a great deal of autonomy and flexibility built into its makeup. But Manda found its human-mimic interface annoying. She kept expecting it to act like a human, and it kept disappointing her.

It leaned toward her. "I've got a secret."

There's no point in whispering, Manda thought in annoyance. Ur-Carli was projecting. If anyone else could see the projection, they would hear the whisper, too. And even if the syntellect had been here in proxy or waldo, whispering would be pointless. On Brimstone, a normal conversational tone was difficult enough to hear from farther than a couple meters away, and the mess wasn't very crowded.

"Something that nobody in the colony knows about," the syntellect continued, in its growly old-lady voice. "I think it will interest you. Do you want to come see?"

Manda sighed in exasperation, then stood. "All right." She might as well get it over with; ur-Carli wouldn't leave her alone until it had achieved its end.

And, despite herself, Manda was curious. What knowledge could a syntellect possibly have that would be of interest to humans?

#

Ur-Carli led her away from the main colony areas, up through the winding, rocky passages and stairways toward the surface. By the time they reached the main lift station no one else was around.

A brownout had rendered the lifts inoperable, so they had to take the stairs: a seemingly endless set of rock slabs coated with ice. Manda soon got winded, and had to stop for frequent rests. Brimstone's oxygen content was higher than Earth's, twenty-five percent, and Manda was all but a native of this planet; they'd made landfall when she was barely a fire-year old, three earth-years. But the human cardiovascular system simply didn't work that well at less than four hundred millibars, an atmospheric pressure comparable to seventy-two hundred meters above earth-sea-level—among the highest of Earth's mountaintops.

After she slipped and fell a second time, Manda sat down on a step and leaned over her knees, heaving labored breaths. Ur-Carli waited patiently on the step above.

I hate you, Manda thought. She was starting to feel the chill, despite her exertions; these upper, unheated tunnels stayed at about minus twenty Celsius. She donned her parka hood and pulled on her mittens and shells. Then she activated the spikes in her boots and stood yet again, cursing herself for going along with this. The syntellect started upward once more.

"Not much farther," ur-Carli said finally. Air stirred on Manda's cheeks. She pulled her hood close with a shiver. If she could feel the breeze down here, through the lock, quite a storm must be blowing. And she didn't have radiation gear with her.

But she was looking forward to a visit to the surface anyhow. One got tired of small, windowless chambers and crowded, meandering, poorly lit corridors—of cliques and political maneuverings, shifting loyalties, lies, nasty little secrets, furtive looks. Going to the surface meant being truly alone, not just hiding out in a simile or sending your consciousness off into the ocean depths in a marine-waldo.

But at the landing twelve steps below the main colony entrance, within sight of the heavy, rotating chains and pulleys of the fuel tanker transport loop, ur-Carli shrank to about three-quarters size, turned, and headed into a cramped tunnel normally used only by the colony's maintenance robotics. It led, Manda was pretty sure, to the main equipment storage hangar. The corridor was rather too small for a human; Manda was forced to walk stooped over.

"Wait," she gasped, but ur-Carli didn't pause. Manda could no longer see a thing except ur-Carli's projection; the colony didn't waste power lighting corridors for robots that navigated solely using radio and internal maps. Manda's tool belt had a flashlight, but she'd left the belt in her locker at breakfast.

So she trudged along behind the syntellect, getting angrier and angrier. About the time she'd decided to put a stop to this and announce that she was heading back, ur-Carli halted and gestured.

"Immediately to your right," the syntellect said, "is an access tunnel with rungs set into it." Its voice, a projection directly into the speakers at Manda's ears, didn't echo as Manda's footsteps and breathing had. "There are twenty-four steps. Be careful—it may be slippery."

Manda shook her head, exasperated. "Why are you doing this?"

But ur-Carli had vanished.

"Goddamnit!"

Manda stood still for a moment, still panting, sparks dancing on the periphery of her vision—on the brink of saying fuck this and leaving. She groped for the access tunnel, defining its shape and size with her hands. The opening was about a meter square, its top at about shoulder height. She stuck her head inside. A dim light shone above, its gentle reflections making the coarse tunnel walls glisten like garnet.

I've come all this way, Manda thought. I might as well see it through. She scaled the ladder and climbed up into a room with thatched flooring and ice-coated walls.

It was a long room, one that stretched back into the dimness. Near this end a tall, narrow window allowed sun- and planetshine in. Manda could tell from the pinkish quality of the light, and the fact that everything had two faint shadows, that both 47 Ursae Majoris, the sun, and Fire, Brimstone's parent world, were up.

Manda shivered. Ice fog from her exhalations stung her cheeks. The room was colder even than the tunnel she'd just left. Thirty below, perhaps? Maybe colder. Cold enough it hurt to breathe, even through the livehood and the fur fringe of her parka, which she pulled close to her lips. She realized she'd left her tam and neck gaiter below. Her fingers had already begun to throb, even through the gloves and shells, and her feet were starting to grow chill, too.

I'd better not linger too long, Manda realized. Her livesuit wasn't the only thing that might give out in this severe a cold. But she had a few moments, at least, before the cold would harm either her or the liquid nano-muscles and -transmitters of her livesuit. She touched her clock icon and set an alarm for ten minutes.

It was then she noticed her connection with the colony network had been severed. She looked around, startled. This room is unplugged! If so, it was the only place she knew of in Amaterasu that was.

From the window, she saw that the view looked out onto the snowy basin within whose mountain borders lay Amaterasu. On the plains below were small musk oxen and reindeer herds, grazing on lichens and snow fungi. She spotted a couple of shepherds and their gengineered dogs with the herd animals. The main entrance to Amaterasu must be almost directly below this place. Manda was surprised that she had never glimpsed this slotted window from below. But it wasn't so strange, really; the window must be hidden by the large promontory that overhung the entrance.

As she'd guessed, a fierce windstorm was blowing outside. Ice crystals struck the glass with a sound like wild applause, or voices shouting, at a great distance.

The sound was hypnotic. Manda pressed mittened hands to the glass and leaned close, till her breath left fractal frost trails on it, and squinted against the snowy brightness. Ice-laden gusts outside obscured, then revealed, the Scimitars: a set of predator-tooth-jagged mountain peaks that rimmed the basin's far side.

She looked upward. Fire, a jovian world two and a half times the size of Sol's largest planet, Jupiter, was faintly visible beyond the ice-crystal clouds. It hung near the horizon, dominating the western sky, subtending twenty-five degrees of arc. She remembered how once as a child she'd stood on the valley floor—staring at that enormous flame-red, white-yellow, and bunsen-burner-blue ball in the sky with its sweeping arc of a ring—watching as massive storms coiled like bands of gaudy-bright smoke across its face, imagining she could reach up and touch it. It looked that close.

Fire wasn't all that near, though. It only seemed so because of its immense size. Brimstone orbited Fire at about 400,000 kilometers—roughly the same distance as that between Earth and its moon—but Fire's powerful pull took only thirty-four and a quarter hours to whip Brimstone around, rather than the twenty-eight days Earth's paltry gravity took to pull its own moon around. They used Brimstone's roughly-thirty-four-hour revolution around Fire—during which time the sun, Uma, rose and set as a result of that lunar orbit—as their "day," and broke this day into two seventeen-hour watches, each with its own work, eating, and rest periods. So each thirty-four-hour, bifurcated day held a total of sixteen hours of work time, with six hours for eating and relaxation, and thirteen for sleep. They wedged an extra work hour in every four days to correct for the difference. Brimstonians worked hard.

To keep synchronicity with Earthspace (Manda wasn't sure why they bothered; they had no contact with Earth and wouldn't for centuries, until they could build their own omni field generator to give them an instantaneous link with Earth. Still, they had to do something to measure time, and she supposed it made as much sense to match up with Earth as not), Brimstonians used a five-day week and a twenty- to twenty-one day month, which made their weeks and months the same length as Earth's. Three twelve-month seasons made up a fire-year. This made Brimstonian weeks and months correspond closely to Earth's weeks and months in length, with each of their seasons lasting an earth-year.

Fire's fiery appearance was strictly an illusion: Brimstone had always been a chilly world; in its warmest days it had never been as warm as Earth. Their sun, 47 Ursae Majoris or Uma, radiated enough heat to make a band along Brimstone's equator, its "tropics," marginally habitable: comparable to the polar regions of Earth. Uma was about as strong as Sol, and Fire and its satellites orbited at a distance of just over two AU; it took them three earth-years to complete an orbit around their sun. Without its once-high carbon dioxide content, Brimstone would perhaps never have been able to harbor life.

And they were certain Brimstone had harbored its own life at one time. (Technically, it still did; their probes had found traces of bacteria and they discovered a couple native, cold-adapted versions of algae when they first landed; they'd used them as templates to modify Earth-based organisms during their early terraforming efforts.) If the high oxygen content in the atmosphere and the large reservoirs of crude oil they'd found weren't indicators enough, they had Amaterasu itself: the geologists believed the caverns' calcite and silicate structures had been some sort of rough equivalent to Earth's coral reefs, billions of years ago—though some argued that the structures might actually have been a fresh-water and/or aboveground biomineral feature, rather than an undersea one. And some of the cavern's strata held the occasional two-billion-year-old partially fossil fragment, evidence of small creatures that must once have inhabited Amaterasu.

But just about everyone besides Manda was certain the world was post-biotic, at this point, other than the few meagre organisms they'd identified before the humans' microbes had taken over. Most of the planet's carbon was now bound up in subterranean hydrocarbon pools and vast glaciers of methane-ice at the poles, and on the ocean floor, beneath the almost-worldwide ice caps, and much of the rest had condensed out of the air gradually as the moon had cooled, forming deadly-cold, smoking carbon-dioxide pools amid and atop the methane-hydrate glaciers at the poles.

Unless Hell had frozen over while nobody was looking, there was nothing brimstone-like about Brimstone. This world was an icy slushball on its way to becoming a frozen-solid snowball, and organic-based life couldn't survive below the freezing point of water.

Pondering this, Manda wandered around the large chamber. A desk and a set of cabinets rested against one wall. Near the desk, a spiral staircase ascended through an open hatch in the ceiling. Intrigued, she climbed the staircase into a small, dark room with metal walls.

Above chin-level, the walls of this room sloped inward toward the ceiling, creating a four-sided pyramid. The only light came from the opening in the floor. Wind pounded its fists against the thin walls, beating them like a drum. In the room's center was a long box, a hand-made affair of metal and bamboo, about half a meter square by about four meters long—the room's only feature. Curious, she groped her way around it and found a wheeled step-ladder next to it, which she climbed. Near the upper end of the rectangle she located an eyepiece; she peered into it and saw nothing but a blur.

It was a telescope!

She spotted a glint out of the corner of her eye, and reached for it: a remote control lay in a basket attached to the hand rail. She picked the remote up, squinted at it in the low light, then fiddled with its levers, which made the telescope tilt up and down and back and forth.

Still powered. Good. One never knew anymore what equipment would still be working from the original settlement, and what wouldn't. The equipment that time and heavy use hadn't yet broken, the severe cold and intense UV emanating from Uma and Fire often did.

The Amaterasans had grown quite clever at fixing things that seemed unfixable, and reformulating broken parts or jury-rigging stand-ins when the original equipment failed. Exodus had been designed as a colonizing ship, stocked with a wide array of equipment that was highly modular, powered by antimatter batteries, and intended for use in severe-environment conditions. And the crêche-born had made a little progress with nanotechnology on their way here, whose fruits the colonists had access to.

Still, it was only a matter of time before all their original technology failed. Even if the equipment itself weren't gradually failing, they had no means of making more antimatter, and all their waldos and robots were powered by it. Already many of the more heavily-used recycling and refining equipment were on their second battery packs. And the crêche-born hadn't left them the means to manufacture replacements, reasoning that these would be needed at their next destination.

So the colonists had had to make do, and come up with ways to survive until they could mine enough ore and build enough infrastructure to manufacture their own technology: a process that would take centuries. According to her siblings' estimates, they only had another fifteen to twenty seasons before equipment failure and battery depletion started putting the colony at risk. They had to start warming this world up, quickly. Hence, Project IceFlame.

Manda fiddled with the remote control some more. A recessed oval button between the levers caused a loud screech when she pushed it. Something started beeping, and a red LED began flashing on a panel by the stair that she hadn't seen at first. She went over, scraped off the frost, and squinted at it. A faded, hand-printed label next to a switch said "De-icer." She flipped the switch.

The beeping stopped, and the red LED on the wall panel went from blinking to a steady glow. Manda could feel on her cheeks the warmth that emanated from a set of glowing coils against the metal ceiling. She spent the next few minutes, while the de-icer worked, fiddling with the telescope's controls, familiarizing herself with them.

A drop of icy water hit Manda on the cheek. She looked up. A faint crack of light showed. Then the red LED went off, and the screeching started again. Manda flinched as the ceiling overhead split into four triangles, which fell away like the petals of a blossoming flower, and a cascade of snow and dust fell onto her. She covered her mouth and eyes, then laughed in delight as the storm blasted her in the face, stinging her cheeks with ice crystals, stealing her breath with its ferocious cold.

Wind whipped over the upright portion of the wall. Manda pulled her hood close again. This little observatory was set on the spine of a ridge, at a wide spot that narrowed again on both sides. Nearby, the colony's lone radio tower stood, a slender, skeletal structure that reached into the sky, trembling in the gusts. The blinking red light at its apex served as a beacon for the herders, waldo pilots, and explorers who wandered Brimstone's surface.

Manda eyed it, buffeted by the wind, hunching her shoulders and stamping her hurting, cold-stiffened feet, remembering how many times she had used it to get her aerial-waldos home. Then she shuddered violently. She had forgotten just how cold it could get, out here in the spring winds. Even if she could tough it out, her livesuit couldn't handle it, and she didn't have her radiation gear. She should get back inside.

But first—shivering, fidgeting—she looked through the eyepiece again, and cranked the knobs until Fire came into focus. Even through the haze of ice-fog she could make out shadows, cast among the white clots of cumulus in Fire's outermost atmosphere, and the swirling, crimson, yellow, and bluish cloud canyons of Fire's upper-middle layers. Fire's ring of ice and rock—its upper half pale gold in Uma's early-morning light, its lower half invisible below Fire's night side—cast a sharp, slender shadow down onto Fire that freefell between the cloud formations like a misplaced strip of night.

Finally she acquiesced to the need for warmth. She triggered the recessed button again, and the walls came back up, screaming their rusty outrage, to shut out the two-toned light and the howling wind. Manda headed back down the spiral stairwell, blew into her cupped hands and did some jumping jacks and stretches to warm up a bit, then checked her livesuit.

She wasn't worried about her yoke; liveyokes were bioptronic systems and much hardier, thermally, than livesuits. But livesuits used a nanobug stew of muscle-like molecules and signal transmitters that was sensitive to extreme cold. The suit's temperature warning readouts were getting jittery, and drifting down toward the danger zone. After a moment's nail-biting indecision, she decided she could squeeze a few more minutes in, to check the dim reaches in the long room's back.

Equipment of unknown function was scattered throughout, along with some machining tools. She wandered into the increasing dimness past the office, through a lab of some kind, past a small machine shop. She spotted a collection of old waldos, both big and small: ancient, broken-down models; dusty hulks that looked like bizarre bugs, monsters, and skeletons in the dimness. She really needed a flashlight to explore here. She couldn't make out much detail. Pale, purple-tainted dust mingled with snow powder had covered every surface and piled up in the corners.

Nobody knows about this place, she realized. It's been forgotten—if anyone ever knew it was here at all. She wondered whose space it had been, and smiled. Well, I guess it's mine now. At least for the moment.

Her eyes had slowly become accustomed to the low light. Beyond the lab she spied an open doorway. She made her careful way there and at the door she paused. The cold's severity irritated her eyes; she blinked repeatedly and stared into the dark room, trying to make out detail. Her shadow stretched thin, faint, and brown across the floor of a small room. A very slight change of odor reached her. She couldn't put her finger on the difference. It was not an unpleasant smell.

Against the wall seemed to be a cot, or a bed. She stepped into the room and her eyes adapted further to the darkness. It was a bed. And someone was lying on it. She yelled in sudden fear—her heart thundered and her mouth went dry. RUN.

But no, the figure hadn't moved when she'd cried out. And the dust was deep enough that behind her, in the faint light coming from the observatory, she could make out its peaks and craters where her feet had fallen.

She was in no danger. No one had walked on this floor in years. It was a proxy, or. She stopped, heart pounding again. Or a corpse. Shit.

There must be a light source, she realized, no matter how old this place is. If it still works. Which it probably does. Why are you stumbling around in the dark? Idiot.

Did she really want to see this?

"Lights up," she said.

And covered her eyes with another shout as the lights came on full force, blinding her.

"Lights down by half!" she yelled. "You stupid shit!"

Ur-Carli had to be watching; it was probably laughing its algorithmic butt off. (Perhaps not, though; not if the room was isolated from the colony network.) Manda blinked hard, eyes burning, and finally worked up the nerve to remove her hands from her eyes and look at the bed again.

It was a corpse. A frozen one, to all appearances perfectly preserved. A very old woman, blanketed by Brimstone's lavender-and-snow dust. Manda released her breath through her teeth and approached cautiously. She blew dust and snow from the face, thinking it looked familiar.

And she realized. For one thing, the corpse's face shared features with Manda and some of her fellow Brimstoners—this woman was certainly a forebear of one or more of the colony's clones, including Manda's.

But that's not what jarred her. What jarred her was that she had seen precisely this face—or rather, a somewhat younger version of it—many times. Most recently only moments earlier, in fact, on ur-Carli.