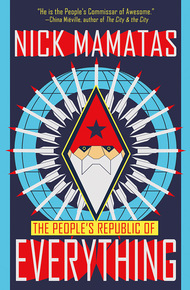

Nick Mamatas is the author of several novels, including Move Under Ground, I Am Providence and Sabbath. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Mystery Stories, Year's Best Science Fiction and Fantasy, Tor.com, and dozens of other venues. Much of the last decade's short fiction was recently collected in The People's Republic of Everything.

Nick is also an editor and anthologist: he co-edited the Bram Stoker Award-winning Haunted Legends with Ellen Datlow, the Locus Award nominees The Future is Japanese and Hanzai Japan with Masumi Washington, and the hybrid fiction/cocktail title Mixed Up with Molly Tanzer. His short fiction, non-fiction, novels, and editorial work have variously been nominated for the Hugo, Shirley Jackson, Stoker, and World Fantasy Awards.

Welcome to the People's Republic of Everything—of course, you've been here for a long time already. Make yourself at home alongside a hitman who always tells the truth, no matter how reality has to twist itself to suit; electric matchstick girls who have teamed up with Friedrich Engels; a telepathic boy and his father's homemade nuclear bomb; a very bad date that births an unforgettable meme; and a dog who simply won't stop howling on social media.

The People's Republic of Everything features a decade's worth of crimes, fantasies, original fiction, and the author's preferred text of the acclaimed short novel Under My Roof.

My own volume, including the satirical short novel Under My Roof, which the San Diego Union-Tribune called "the great American suburban novel"—The People's Republic also includes everything from a Lovecraftian pastiche written by an AI to a steampunk Friedrich Engels saving the Little Match Girls. – Nick Mamatas

"Each tale is entertaining on its surface, but all hold a deeper meaning . . . This collection will be an easy sell to readers who enjoy genre-blending authors of thought-provoking and topical tales, such as Jeffrey Ford, China Miéville, and Jeff VanderMeer."

– Booklist, starred review"The 15 stories in Mamatas's strong collection show impressive imaginative range, cutting across the boundaries of fantasy and science fiction and veering into territory that defies genre pigeonholing."

– Publishers Weekly"Bay Area author Nick Mamatas is renowned in his work and in his online presence as witty and perspicacious; his new collection will bolster that reputation . . . brilliant, oddball."

– Seattle Times"The People's Republic of Everything is a subversive and darkly humorous collection of stories showcasing author Nick Mamatas's ability to work across a variety of genres."

– Shelf Awareness"Mamatas is such a great novelist that it's easy to forget he also writes superb short stories. This collection is a testament to his short-form chops, and a powerful one at that."

– LitReactor"A whole lot of these stories could be described as 'revolutionary'—both in the sense of involving actual revolutions on small and large scales, and regarding the author's tendency to recombine the materials of SF, crime, literary, and experimental fiction in new and provocative ways. To which I can only say—long live the revolution."

– LocusFrom "Under My Roof"

My name is Herbert Weinberg. I know what you're thinking. That sounds like an old man's name. It does. But I'm twelve years old. And I know what you're thinking.

In fact, I'm sending you a telepathic message right now.

Yes, it's about the war. And yes, it is about Weinbergia, the country my father Daniel founded in our front yard. And yes, I have been missing for a while, but I'm nearly ready to go back home.

But I'll need your help. Let me tell you the story.

It was Patriot Day, last year, when Dad really went nuts. Thoughts were heavy like fog. Not only was everyone in little Port Jameson remembering 9/11, they were remembering where they were on September 11th, 2002, September 11th, 2005, 2008, on and on. The attacks were long enough ago that the networks had received a ton of letters and email demanding that they finally re-air the footage of the planes slicing through the second tower, because nobody wanted to forget. Schools took the day off. Banks closed. Some cities set up big screens in public parks to show the attacks. I was excited to finally see the explosions myself. Nobody else could really picture them properly anymore. I drew a picture in my diary.

My mother Geri had forgotten pretty much everything except how beige her coffee was that day. She had been pouring cream into her blue paper cup when she looked up out of the window of the diner and saw the black smoke downtown, and she had just kept pouring till it spilled over the brim. She found my father later that day and told him that they were going to move to Long Island immediately.

And they did. Every year since, she forgot a little bit about that day. What was the name of the diner? Did she order a bagel with lox or just the coffee? Did she think it was Arabs or did the liberal centers of her cerebellum kick in to say, "No no no it could have been anybody"? Did she want to kill someone? Drop an A-bomb on the entire Middle East? She didn't know anymore. All she remembered, and all I plucked out of her head, was her off-white coffee.

My father Daniel, on the other hand, didn't remember anything but the nuclear weapons. Dirty bombs, WMDs, suitcases filled with high-tech stuff; that was all he could think about. He took a job mopping floors at SUNY Riverhead so he could take classes for free. Physics. Mechanical engineering. His head was like an MTV video—all equations, blueprints, mushroom clouds, people running through the streets, and naked ladies, in and out—flipping from image to image. With every war Daniel got more frantic. The president would say some stuff about not ruling out nuclear weapons, and I could tell he wasn't kidding. My father would stay up all night, just walking around the dark kitchen and smacking his fist against the table. On the news, they kept showing more and more countries on a big map, painted red for evil. All of Latin America was red now and even the normal people in California died when someone ran the border with a bomb or shot down a plane over a neighborhood.

Dad read the newspapers, spent whole days in the library and all night on the computer. He was getting fat and losing his hair. He was a real nerd though, so nobody really noticed that he was slowly going mad. Actually, the problem was that he was going mad more slowly and in the opposite direction from everybody else. At night he dreamed of being stuck on an ice floe or on the wrong side of a shattered suspension bridge. Mom and I would be drifting off to sea on another ice floe or sliced in half by snapping steel cables. Then Dad would see the ghosts of firefighters and cops, white faces with no eyes, and they would point and laugh.

So Daniel studied. Researched. Thought of a way out.

Dad waited until I was out of school for the summer to make his big move, because he knew I would make a good assistant. He was laid off by SUNY because of budget cuts—Mom blamed his erratic behavior, but Daniel wasn't really any more eccentric than his other co-workers. He sold his nice car and bought a ratty old station wagon even junkier than mom's Volvo hatchback, and spent all day tooling around in it, while Geri clipped coupons and made us tuna fish with lots of mayonnaise for dinner. They didn't send me to genius camp that summer (I'm not really a genius, I just know what smart people are thinking) so that's how I ended up being Prince Herbert I of Weinbergia.

Dad woke me early one hot day, just as the sun was rising. He looked rumpled, but was really excited, almost twitching. I half expected to see a little neon sign blinking Krazy! Krazy! Krazy! on his big forehead like I did back when Lunch Lady Maribeth went nuts and started throwing pudding at school, but he was actually normal.

"C'mon Lovebug, I need your help," he said, shaking my ankle. He hadn't called me Lovebug since fourth grade, and his mind was going three thousand miles an hour, so I didn't know what he wanted.

"What is it?"

"We're going to the dump to look for cool stuff. C'mon, we'll get waffles at the diner on the way back."

I always wanted to go to the dump and look for cool stuff. I was really hoping to find something good like a big stuffed moose head or a highway traffic sign, but then in the car Dad told me that we were going to look for the ingredient that made America great.

"In fact, they call it Americium-241. It was isolated by the Manhattan Project, Herbert." Daniel loved to talk about the Manhattan Project.

"I don't think we're going to find that stuff at the dump, Dad."

"Smoke detectors, son. Most smoke detectors contain about half a gram of Americium-241," he said with the sort of dad-ly smile you usually just see on TV commercials.

"How many grams do you want?"

"Well, 750 grams is necessary to achieve critical mass, but we'll want more than that to get a bigger boom," he said. He was thinking about turning on his blinker and how much smoother the ride in the old car was, not about blowing anything up. "I guess we'll need about 5000 smoke detectors."

"Uh . . ."

"Don't worry. I don't plan on finding all of them today."