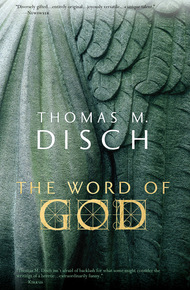

Thomas M. Disch was a bestselling novelist, poet, and book critic. His work was featured in the New York Times, Entertainment Weekly, Harper's, The Nation, and the Hudson Review of Books. Disch was a major figure of science fiction's new-wave movement. His books included Camp Concentration, On Wings of Song, The Word of God, and The Brave Little Toaster. His nonfiction book about poetry, The Castle of Indolence, was nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award. John Clute famously described Disch as "perhaps the most respected, least trusted, most envied, and least read of all modern first-rank SF writers."

The only tome ever written by God Himself—inspired by actual events!

In this compelling memoir, the first and hopefully the last of its kind, America's most divine author reveals the intimate and shocking details of His sudden elevation to the most coveted and least understood position in the universe.

In early 2005 (A.D.), wearying of the world's religious schisms, doctrinal heresies, and manifold editorial sins, Thomas M. Disch took matters into His own hands and became the Deity. Now, as controversial as it is incontrovertible, here is the moving true story of His awful transformation and its awesome aftermath reveals, at long last, the hidden web that links Disch, Philip K. Dick, Western wear, the Leamington Hotel, and Eternity itself. Read it in fear and trembling...but read it, or else.

Author Thomas Disch took seriously the idea that the novelist is God. Well, not seriously, but satirically. The Word of God deflates religion, and even casts Philip K. Dick as a kind of Satan to Disch's titular deity. Not for the squeamish, or the very devout—or maybe that is exactly who needs to read this! – Nick Mamatas

"The careful reader will tease out many solid truths from the tangle of humor, history, surrealism, and speculation. The density of ideas packed into this short book is as impressive as Disch's mastery of his craft."

– Publishers Weekly, starred review"Movie Pitch: Bruce Almighty as a pitch-dark Charlie Kaufman dramedy…a fitting coda to a career spent perfecting the art of the unsettling. Grade: A-."

– Entertainment Weekly"Thomas M. Disch isn't afraid of backlash for what some might consider the writings of a heretic…extraordinarily funny…."

– Kirkus:…amusing and subversive…. SF veteran [Thomas M.] Disch fires another salvo in the ongoing debate between atheists and believers."

– Booklist"The god Disch is brilliant, startling, playful, vengeful, poetic, and kind of scary. As gods go, we could do worse. The writer Disch is brilliant, startling, playful, vengeful, poetic, and kind of scary. As writers go, there is no one better."

– Karen Joy Fowler, author of The Jane Austin Book Club"A lovely, funny, interesting, incisive, and wonderfully blasphemous novel."

– Jeff VanderMeer, author of AnnihilationChapter One

Let there be light.

There, the word is spoken and the universe has been brought into existence, and the Enlightenment along with it. We'll proceed from there. The important thing, always, is to have made a beginning.

That's certainly been the way when I've written fiction, and Holy Writ probably works the same. The title was no problem at all. It came in the proverbial flash. Whereas the subtitle has kept morphing ever since. Earlier versions have been variations on "And How You Can Be Too" or its opposite; then, off on another tangent, "Memoirs of an American Divinity." The latter, a tip of the hat to the transcendental tradition that covers such a broad range of Yankee divines as Emerson, Ann Lee, Joseph Smith, Mary Baker Eddy. Not all of them gods of an absolute and omniscient variety, like me, but prophets who've felt themselves to be on a par with Mohammed and whose scriptures have been accorded a similar reverence by large numbers of their fellow citizens. As polls keep showing, and media is ever reminding us, we Americans are a very religious nation, whose natural element is belief.

As to the revelations I mean to unfold, many will be of that traditional High Utterance that lays down laws and offers delectable previsions of heaven and saber-rattling fantasies of enemies horribly revenged, but there will also be talks of a friendlier locker-room character (the more American side of the vision), with homespun scriptures sometimes verging on whimsy. But nowhere will there be irreverence. Indeed, it's precisely in the more playful and paradoxical passages that seekers may find the touchstones of a perfected faith, for faith is never more perfectly rooted in the soul than when one can truly believe in something one knows to be preposterous, like Noah's Ark. Christ had a special love for children and for simpletons (the poor in spirit); I can do no less.

Years ago, back before I knew myself to be divine, I lived next door to two Mormon missionaries in the Mexican town of Amecameca, an hour south of Mexico City. In all of Amecameca, they were the only other people who spoke English, and they delighted, in a true missionary spirit, in arguing about religion, and in particular they liked to controvert Darwin and his theory of evolution.

They had books filled with gorgeous views of the Grand Canyon, which (it was maintained) had not been formed by the long drudgery hypothesized by secular humanist geology textbooks but assembled from raw materials in the time it takes to make an omelet. That this flew in the face of orthodox scientific wisdom was clearly a source of pleasure to my two neighbors.¹ Logical difficulties only kindled their faith to a brighter glow and made their voices louder.

It is the special beauty of faith, that, like the fabled Phoenix, it draws its life from the flames that destroy it. It flies as it dies. A moth is the same in some ways, and it is the business of gods and of their prophets to light such beguiling flames that the faithful cannot escape their supernal charm. The Jonestown suicides in Guyana, the Aum Shinrikyo cult's intended massacres, and militant Islam's achievements across the globe are all instances of the destructive power of faith. I'd like to assure my own faithful readers that I don't intend to lure them to any such immolation of themselves and others. If that makes me seem a lesser sort of a god, so be it. Like Christ, I shall defer slaughter and reprisals to the afterlife. Here and now, in the little time remaining, my enemies and competitor-gods will find that their threats and execrations will be powerless against the buckler and shield of my divine equanimity and sense of humor. All my justice shall be poetic.

The Greek gods were good at the same sort of thing, the way they'd find some fitting metamorphosis for anyone who pissed them off, turning house-proud Arachne into a spider and beautiful Io into a cow. But their cruelties and vendettas were not their defining features, nor yet their loves, wonderful as those were. Their beauty, then? Surely, that was a considerable asset, and any worshipper allowed inside one of their temples for a glimpse of Zeus or Apollo or Venus or Minerva must have been unnerved and overawed by their larger-than-life stature and command of good form. Gods then were expected to look terrific.

The Jews and their fellow monotheists had a less capital-intensive ideal: their god was just a voice in their heads — at least most of the time. Or words in a book. (Like the words in this book? You well might ask.) Their beauty did not need the high-priced skills of a Phidias, just a capable script-writer and a lector of sufficient charisma. It helps to have a naive audience, of course. Any parent can play Santa, and shamans don't need a college degree. The holy writings of Joseph Smith and L. Ron Hubbard will never qualify either prophet for inclusion in the Library of America. (And my own chances in that regard? They might seem slim, but only God knows what may happen in the fullness of time — and I'm not telling!)

Literary merit doesn't matter much with Holy Writ. What matters is the faith that its faithful can bring to it. In dramas of faith the spotlight is always trained on the believer, on the born again sinner being dunked in the baptismal pool or the martyr being thrown to the lions or the Palestinian child swaddled in the ammo-belts of his or her exemplary suicide. Their astonishing actions act to authenticate the gods they believe in. Doubt their gods and the believers' lives have been in vain. That's why it is good manners and simple prudence not to be express skepticism about the faith of strangers.

Again, I hasten to assure readers that I do not mean to solicit their self-immolation or even their total immersion in the pages ahead. I do have a program for the conduct of American foreign policy, and a few simple rites and superstitions I would have you observe, but I'll hold off on those things until we know each other better and I have been able to explain the tenets of our faith — and its commandments.

The first of which, like that of the Mosaic law, is that you stay seated where you are and continue reading this Holy Writ and have no other gods before you, nor any other author, for at this point in the drama of your conversion the two amount to the same thing. Not that there will be any terrible consequences if you put this Writ aside and enjoy some other licit pleasure for a while, for as I am not the kind of divinity that insists on corporal punishment now or in the hereafter, not even of such an indirect or nonmiraculous kind as tornados or the arthritis I have to put up with. Life is hard enough in those regards without God adding to it.

Of course, doubters will experience an inner spiritual anguish of indescribable intensity as a result of being removed from my divine presence, but (here's another fine divine paradox) they won't know that they're in such a wretched state, just as the congenitally blind don't know what they're missing vis-à-vis vision.

Does all this begin to seem silly? It should. Pompous and grandiose? Absolutely. That has usually been my response to those zealots who have threatened me with fire, brimstone, and eternal punishment. I suspect them, as well, of ill-repressed sadistic tendencies, as though they would not be averse to administering some of their promised torments themselves, as agents of the latest holy inquisitions, if only they were not required elsewhere to sing in the heavenly choir.

So is this Holy Writ or isn't it? Am I being serious? Yes, and then some. What I propose to write about in these sacred pages is what the whole God-business looks like to someone who not only doesn't believe in God but who, moreover, doesn't believe in the belief of those most aggressively pious, most loudly devout. The only way effectively to convey my own sense of the matter is to arrogate to myself the same absolute authority, the same more-than-Papal infallibility, the same maddeningly smug chutzpah that True Believers of all varieties have armed themselves with: the Jesus freaks and Jehovah's Witnesses, the Tartuffes and Elmer Gantrys, the imams and ayatollahs, the redneck judges with two-ton Tablets of the Law they want to plunk down on the courthouse lawn and the archbishops campaigning against abortion, all the while they play three-card monte with their cadres of pedophile priests. To paraphrase a popular song, if they loved God half as much as they say they do, they wouldn't do all the things we can see them do.

¹ Their names, I confess, I have forgotten. Even God nods.