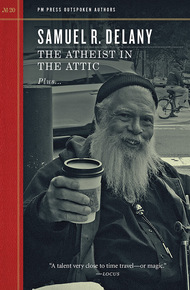

Born into a distinguished Harlem family, Samuel R. Delany was a success at nineteen, changing the tone, the content, and the very shape of modern science fiction with his acclaimed novels and stories that bridged the apparent gap between science and fantasy to explore gay sexuality, racial and class consciousness, and the limits of imagination and memory. His vast body of work includes memoir, comics, space adventure, mainstream novels, homosexual erotica, and literary criticism of a high order. Until his recent retirement he was a professor of English and creative writing at Temple University.

The title novella, "The Atheist in the Attic," appearing here in book form for the first time, is a suspenseful and vivid historical narrative, recreating the top-secret meeting between the mathematical genius Leibniz and the philosopher Spinoza caught between the horrors of the cannibalistic Dutch Rampjaar and the brilliant "big bang" of the Enlightenment.

Plus: equal parts history, confession, complaint, gossip, and personal triumph, Delany's "Racism and Science Fiction" combines scholarly research and personal experience in the unique true story of the first major African American author in the genre. And featuring: a bibliography, an author biography, and our candid, uncompromising, and customary Outspoken Interview.

"A talent very close to time travel—or magic."

– Locus"The most remarkable prose stylist to have emerged from the culture of American science fiction."

– William Gibson"I consider Delany not only one of the most important science fiction writers of the present generation, but a fascinating writer in general who has invented a new style."

– Umberto Eco"Philosophy is homesickness. It is the desire to feel at home everywhere." —Novalis (as cited in Thomas Carlyle's essay of 1829)

Shortly after I accepted employment with the duke, John Frederick, in November 1676, I, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, arrived at the house of the Amsterdam acquaintance with whom I'd be staying for three weeks while performing legal offices for my patron. By the end of my second afternoon I had made a five-hour trip for a six-hour visit to Baruch Spinoza's home in The Hague (the first of three visits over three consecu- tive days). Back in my Amsterdam rooms, I thought over those hours. I was thirty when I wrote these reflections—wrote them rather too freely, I now suspect, given what has occurred since his death three months after our meeting, as well as over the last twenty-two years of my life. (Gunter and his sisters have divided themselves between Africa and the New World. Would you believe it from what I've written below? I wouldn't.) Since the death of Ernest Augustus and the ascension of George, I've reread it. But I don't think I shall rewrite it, since in two years the eighteenth century will open up about us—or enfold us in its chaos.

1.

There was nothing grand about his home, which almost all things here—the candelabra on the lace cloth at the ends of the down- stairs dining table, the brass bar holding the carpet to the back of each broad step, the yellow blossoms brocaded on the wand of the bed warmer leaning by the fireplace in my bedroom suite— make me remember. (Though severity is in keeping with the nation, domestic Dutch decor is too austere.) In the few hours I've been back I've seen three servants: one man coming from a door at a second-floor corridor's end and (I glimpsed them over the banister) two women walking together across the front hall. They were carrying starched lace toward the dining room, as I was going up.

No Peytor yet, but apparently he was among the lowest in the house.

Gunter does not live opulently. He keeps a household staff here of only sixteen, for him and his three younger sisters—one of whose conversation and anecdotes about her travels I find more interesting than Gunter's; one of whom I find a lively talker about fashion and gossip, if the topic itself is a bit tedious for me; and none of whom is currently at home. From my last visit two years ago, I suspect all three girls find their younger brother a bore.

But aren't journals such as this basically occasions for candid assessments?

No. They're not. They're for telling oneself the fictions that are as honest as you can make them and still keep your life bearable.

Sixteen in this house is not quite one servant for every two rooms.

2.

There, of course, I'd seen only one—and would have been surprised were it more than two. The woman who'd answered the door turned out to be the landlord as well as the red-brick building's owner. An owner answering her own door? That's very Dutch. Or seems so to a German like me.

But I write this back at Gunter's.

Yesterday morning just before daybreak I took a cart up from the boat (I am so glad the duke owns his own yacht), with my three trunks containing eight pairs of pants, a dozen lace-fronted shirts—party and plain—jackets for everyday wear, enough wig powder to choke a full reception of young officers, my travel cloak, my greatcoat, my smallclothes—since baths are at a mini- mum I travel with lots of them, which makes me eccentric—my mechanical calculating machine (my own design, with just the fewest suggestions from the Hamburg horologist who construct- ed it last summer according to my seventeen pages of careful plans) stored with my books (some of mine for casual gifts, two of his I hope no one but he will know—while I'm here—I have) and papers in my luggage—and my calculus still in my head. That's where I want to keep it right now, ready for the upcoming attempt at friendship in England.

Moonlight and window light had flecked the broken canal. The three of us in the Duke's party staying in the city crossed on an early ferry. Horses huffed out breath and hoofed at cobbles, and the deepest blue emerged above the water and was reflected in it; nor was the air that cold.

And today I am back again—from my first visit.

Settling into my suite, where I'd slept a few hours and risen before three in the morning, I'm trying to make sense of the fragments of these last hours, these last days, this life, and the possible world that might sensibly hold both a here and a there.

Today was my first visit anywhere since I'd arrived, you see. Or, for accuracy, I could say it was my second. "One" is the easy fiction. "Two" is the slightly more embarrassing one that society, good manners, and expediency compel:

I did it. It wasn't that important. Let's leave it out. I would have felt very bad if I hadn't at least thanked that

young man back in Hamburg who'd cast his wheels and cogs, and bolted his cylinders to their metal rack, and his grown daughter of almost thirteen who'd polished them all, and his father who'd actually come in one day and made the two suggestions that allowed the whole thing—as I said above, or did I say it?—to work. Did I thank them? The uncertainty throws guilt over all my present actions. But experience says forget it—or write him a note apologizing for the oversight if it's still that disturbing. Writings that have come down to us from the classical Greeks suggest those bright people had a mail service of sorts. But most of the last thirty years in Germany, save in the larger cities, there has not been.