"Jeff VanderMeer is a three-time winner, thirteen-time finalist for the World Fantasy Award. His Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction, the world's first full-color, image-based writing guide, is now out from Abrams Image. His Southern Reach trilogy (Annihilation, Authority, Acceptance) will be published by FSG, HarperCollins Canada, and The Fourth Estate (UK) in 2014, as well as 12 other countries. The film rights have been optioned by Scott Rudin Productions and Paramount Pictures. Prior novels include the Ambergris Cycle (City of Saints & Madmen, Shriek: An Afterword, and Finch) and Veniss Underground. His short fiction has appeared in American Fantastic Tales (Library of America), Conjunctions, and many others. He writes nonfiction for The Washington Post, the LA Times, The Guardian, and many others. He has lectured at MIT and the Library of Congress and helps run the Shared Worlds teen SF/Fantasy writing camp out of Wofford College. With his wife Ann he has coedited several iconic anthologies, most recently The Time Traveler's Almanac and The Weird."

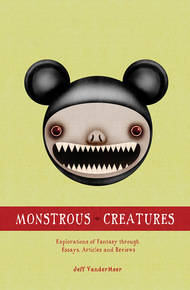

An entertaining, eclectic chronicle of modern fantastical fiction, Monstrous Creatures delivers incisive commentary, reviews, and essays pertaining to permutations of the monstrous, whether it's other people's monsters, personal monsters, or monstrous thoughts. A two-time winner of the World Fantasy Award, Jeff VanderMeer is one of speculative fiction's foremost voices. For the past 20 years, he has not only written weird literary fiction translated into 20 languages, but written about it extensively, influencing the way people think about fantasy through reviews in major papers like The Washington Post and The New York Times, as well as through interviews, thoughtful essays, blog posts, teaching, and guest-speaking. Monstrous Creatures, a follow-up to his 2004 nonfiction collection Why Should I Cut Your Throat?, collects all of his major nonfiction from the past five years, including such controversial pieces as "The Romantic Underground," "The Triumph of the Good," and "The Language of Defeat". Interviews with writers like Margo Lanagan and China Miéville are an added bonus, creating a dialogue with VanderMeer's own interpretations of the monstrous in the fantastical.

"A selection of reflections, interrogations, and dialogues about the state and nature of fantastic literature from the perspective of one of fantastika's most discerning writer/editors. The collection puts forth not just VanderMeer's thoughts on making art, genre, and literature, but elaborates his idea of "the monstrous" and how it informs a variety of works and trends….It is the most incisive collection of reflections and criticisms that I have read in years."

– SF Signal"Jeff VanderMeer's collection contains fireworks explosions of insights into the nature of the weird and a fine introduction to a number of rather obscure writers that most fans of the fantastic likely do not know."

– PopMatters"VanderMeer has jammed his scalpel into the heart of the beast, here. The first essay alone is worth the price of admission. It's staggering. … it's like a best-of record for the wild and fast discussions of art, literature, and monstrosity born of the beehives of the blog-o-sphere."

– J.M. McDermott"[VanderMeer] writes with an amazing intelligence and breathtaking breadth of knowledge. His reviews are insightful and sometimes toe-curlingly honest."

– Hi-Ex ComicsThe Language of Defeat

Clarkesworld Magazine, 2008

I have heard, more times than I care to admit, what I call the language of defeat. I've heard it on panels and on blogs, at genre conventions, at books festivals, and at academic conferences over the past decade.

This language of defeat has to do with accepting a paradigm of the fiction world as "us" versus "them," of "mainstream" versus "genre." I use quote marks around "genre" and "mainstream" because I do not believe these terms are as monolithic or as meaningful in practice as we think of them in theory. The "mainstream" and "genre," if we must subdivide in this way, are both various, rich, and fecund traditions, with many strands and diverse lineages. (In many cases, the two intertwine in such an incestuous way that separating them from each other is a job for a trained genealogist.)

In most cases using this kind of language leads to a bemoaning of the lack of acceptance by the "literary mainstream." It also leads to a certain resentment on the part of "genre" writers, especially centered on the idea that some "mainstream" writers get away with writing "genre" books. We've seen this attitude a lot lately—focused on writers like Margaret Atwood for her Onyx & Crake, Jeanette Winterson for The Stone Gods, Cormac McCarthy to a lesser extent for The Road, and even the work of Jonathan Lethem in a general way, once accused of abandoning his "genre" roots. The negative attitudes toward these books and authors have three layers or premises: (1) that it is somehow inherently wrong and rude for these writers to write in what is so clearly a "genre" milieu (without asking first?), (2) that these authors' cliché comments disavowing their books as "Science Fiction" or "Fantasy" somehow reflect negatively on the quality of the actual texts, and (3) that these forays into forbidden territory are written with no regard for or knowledge of "genre" predecessors.

All of these assumptions tie into the language of defeat because they constitute a kind of wall or barrier in people's minds to acceptance of the work as it exists on the page. And what I mean by this being the language of defeat is that it pre-loads any discussion to appear self-pitying and shrill, weighted down with envy. It also severs the link of responsibility, in that we are no longer talking about individuals or individual institutions, individual gatekeepers, but instead a shadowy them—an enemy without a face, as amorphous as mist.

The language of defeat also requires participants to wade through decades of grudges, jealousies, and insecurities passed down through the generations in the form of received ideas, anecdotes, and assumptions that constitute genre's least useful heirloom.

In fiction, received ideas (which manifest as cliché) are death, but we seem unable to think except in terms of generalizations when it comes to the frustrations and concerns of the writing life. It is much easier to take on the language and ideas of the supposed oppressor and exist in a world where our failures are someone else's fault, and where if only the roadblocks were removed, the ivory towers razed, the truculent, generic, nameless gatekeepers executed, and their heads put on spikes, everyone would get their proper due.

This then is the language of defeat, the acceptance of one's status as victim whilst mouthing the words of dead people from panels past—even being willing to channel the syntax of our defeat, as if we were all pessimistic travelers from the past.

I would like to see a few things change in the future. I would like to see less hyperbole and angst about so-called "mainstream" forays into the "ghetto" of genre. I would like to see all writers make a better effort to see the work of their fellows with eyes unfettered by received ideas as conveyed through whatever label has been slapped on a particular book or author. If we wrote fiction the way we talk about genre and mainstream most of the time, we would all be hacks, our prose full of the most crass and belabored clichés. Yet we persist in outdated, dangerous generalizations, and allow them to color our perceptions of reality. We refuse to engage with the individual in front of us, to communicate, and instead create badly-made fictions about them.

I remember clearly one panel at a Slipstream conference in Georgia that included the iconic SF figure of Bruce Sterling and first novelist Mary Doria Russell, who had written The Sparrow, a SF book marketed to the mainstream. Sterling dismissed Russell's legitimacy throughout the panel, mostly because of a sense of profound insecurity. This work was not from genre, therefore it was not genre. Later, Russell revealed that her chief mentor and first reader had been the famous Analog magazine editor Stanley Schmidt, who had commented on several drafts.

On another panel, I remember genre writers bemoaning their inability to sell fiction to the prestigious literary magazines—the literary world was ignoring them. Someone asked them how often they submitted to literary magazines. After some hemming and hawing, they all admitted that they rarely submitted to such publications. Later on, one even admitted that he wouldn't submit to most literary magazines because genre magazines paid better.

So, in short, the literary world was thwarting them from achieving wider success by not sneaking into their homes, figuring out their computer passwords, and checking out the drafts on their hard drives.

There are similar stupidities perpetrated on the mainstream side of things. For example, when a reviewer pitched a review of my novel Shriek: An Afterword to a prestigious literary journal, the answer was "why would we want to promote some genre novel?" The review was published, but only after the reviewer was forced to add language amounting to "even though this is genre, it's worth your time." But, again, this was one publication, one editor, and to extrapolate from that single point of anecdotal contact some larger commandment applying to some mythical "literary mainstream" constitutes a form of madness.

As for equivalent jealousies on the "mainstream" side, your average "literary" writer, even some Pulitzer Prize winners, might sell, at best, three or four thousand copies and look across the aisle enviously at a mid-list SF writer selling fifteen thousand copies, with a correspondingly higher advance. They—and already you can see how I enter into the dangerous territory of generalities just by using a pronoun—can also be envious of the ease with which much genre material makes the transition into pop culture, and into media such as movies, comics, and television.

The fact is, we all have our wounds, our defeats, our Waterloos. We all look up ahead at some person or group that seems to be doing better than us in some way. The trouble occurs when we perpetuate cliché and stereotype and received ideas as if they were immutable truth, or commonsense, or even, god forbid, wisdom.

Do you know why? Because when enough people keep saying something, the weight of those words becomes a kind of perceptional or operational reality, and not only do we lose opportunities to build something unique and fresh, but we also make the world a duller, less interesting place. We deny the true complexity of the world, and our place in it.

But perhaps just as importantly, the continual perpetual motion machine of this kind of approach wastes our time and saps our energy. It is a quintessentially negative message that moves the average reader, not versed in the stylized symbolism of the ghetto, to two main reactions: pity for the downtrodden and a desire to help the poor victim do better, usually with lots of helpful suggestions that have been trotted out and tried a thousand times before. (Besides, the panelists tackling such questions at conventions often don't really want answers—they just want to wallow in the lovely misery of being victims.)

When that happens, the messenger and the receiver of the message become trapped in the old paradigm. Instead of a genuine and articulate discussion that is, as much as possible, about the books or authors being examined, we enter into an argument that is mostly about defenses, battlements, territorialism, and pettiness.

It is easy to fall into cynicism and become fatalistic. Sometimes, there are perfectly honest catalysts that create an outlook of this kind. But that doesn't mean we have to live in that place, or make other people live there.