CHRISTINE MORGAN'S short fiction has appeared in dozens of anthologies, as well as the collections The Raven's Table and Dawn of the Living-Impaired and Other Messed Up Zombie Stories. Her novels include White Death, Lakehouse Infernal, Spermjackers From Hell, the forthcoming Murder Girls, and others. She is a regular contributor to The Horror Fiction Review, has twice earned an Honorable Mention in Ellen Datlow's Year's Best series, and been nominated in various categories of the Splatterpunk Awards. Christine currently lives in Portland, Oregon.

Listen…

The furious clangor of battle. The harrowing singing of steel. The desperate cries of wounded animals. The gasps of bleeding, dying men. The slow, deep breathing of terrible things–trolls, giants,draugr–waiting in the darkness. The wolf's wind howling, stalking like death itself. The carrion-crows, avaricious and impatient, circling the battle-ground, the Raven's Table.

Listen…

The skald's voice, low, canting, weaving tales of fate and heroism, battle and revelry. Of gods and monsters, and of the women and men that stand against them. Of stormy Scandinavian skies and settlements upon strange continents. Of mead-hall victories, funeral pyres, dragon-prowed ships, and gold-laden tombs. Of Ragnarok. Of Valhalla.

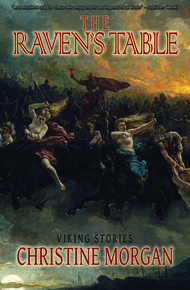

For a decade, author Christine Morgan's Viking stories have delighted readers and critics alike, standing apart from the anthologies they appeared in. Now, Word Horde brings youThe Raven's Table, the first-ever collection of Christine Morgan's Vikings, from "The Barrow-Maid" to "Aerkheim's Horror" and beyond. These tales of adventure, fantasy, and horror will rouse your inner Viking.

Christine Morgan's Viking stories, complied at last! Ross Lockhart says, "Morgan's story "The Barrow-Maid" has haunted me since I first read it. She's an outstanding writer, capable of telling compelling, heart-rending stories in any mode or genre she attempts."

"These works have the sure, solid feel of a talented author deeply engaged with her source material and genre. They're an excellent read for those who enjoy myths and legends of all kinds."

– Publishers Weekly (starred review)"The Raven's Tablefinds the horror at the heart of Viking culture. The stories scare you silly and creep you out at the same time that they shed real light on life in the medieval North. Want to know what it really felt like to live in the Viking Age? Read this book!"

– Michael D.C. Drout, Professor of English and Director of the Center for the Study of the Medieval at Wheaton Collegefrom "Nails of the Dead"

A corpse-cart comes, heavy-laden and rumbling, wheels churning thick in the muck. The ox plods along with head lowered against rain mixed with spattering sleet.

I wait.

The driver and his boy keep their heads down as well, shabby cloaks wrapped around them, hoods drawn over their gaunt faces.

I wait and I watch.

They pay me no notice. Even the ox is oblivious to my lurking, hidden presence. If they had a dog with them, it might be another matter … some dogs are my friends, some, but by no means all.

The boy coughs. It is a wet, weary sound.

He is plague-stricken.

The sickness spread across the countryside like a savory rumor. Neighbor to neighbor, friend to friend. And, like a rumor grows greater and stronger in the telling, so too did this.

The driver says nothing, makes no gesture of comfort. He nudges the ox with the goad. The beast obligingly turns toward the funeral-pit that was, in days not so long distant, a rocky hollow at the village's edge.

They have a night of grim work ahead.

So do I.

The cart stops. The driver climbs down. His boy, still coughing, follows. They take hold of an old woman. Her hair trails grey and fine as cobwebs. Her limbs are bony sticks. Her fingers, deep-grooved from a lifetime of distaff and spindle, thread and loom, seem to scratch like hooked claws at the dark-clouded sky.

They lift her, and carry her, and swing her, and let her go.

Down the corpse falls, a stiff and brittle bundle.

Into the pit. One more for the pile.

Birds flap up, protesting at the disturbance. Gulls, mostly; Odin's ravens, for all they are greedy corpse-pickers, fancy themselves too noble for this feasting bounty. Rats scurry, squeaking and indignant. The lesser carrion-eaters, worms and beetles, go unconcerned about their business.

A child is next.

This is the way of such things. The weakest are often first to succumb … the very old, the very young, the poor and the frail. But, ultimately, no one is safe. Lord or thrall, hall or hovel, no one is safe.

I continue waiting and watching as they unload the cart of its burdens. Bodies tumble like logs. Cold, dead flesh slaps and smacks onto the rain-slick rotting mound below. The stench, already a tangible thing, worsens. The belch and sigh of released gases … decaying organs rupturing upon impact … it is a reeking, pale miasma hanging in the air, felt and tasted as well as smelled.

The boy stumbles, gorge heaving. He does not vomit, but as he gags and retches, he begins again to cough. He coughs until he drops, choking, to his knees. Blood-foam flecks his scabbed lips. The sound is terrible, thin and desperate wheezing gasps between each ragged lung-ripping spasm.

He collapses, face-purpled, watering eyes wide and pleading. His trembling hand outstretches. It is gore-streaked, filthy, grime caked under the nails in thick black crescents.

The driver, with a pained expression, turns away. He puts his back to the dying boy. His shoulders shake. At his sides, his fists clench white-knuckled. He seems to stare unseeing in the direction of the village, where so few thin threads of smoke unspool from chimneys.

Then it is over. A final rasping gurgle escapes the boy's throat. His body goes limp. Rain washes the bloody foam from his lips. Sleet melts in his eyes.

I watch in great interest.

I am no stranger to death or the dead.

The dying, however, I do not often witness. I follow later, like the rats and gulls, like the worms and beetles, like the proud ravens and those dogs who are not so loyal as to refrain from feeding on the remains of their former masters.

I watch now as the driver covers the boy's face and wraps him in his cloak. He sets this one aside, treating it far more gently than the others in his care.

Working alone, he resumes the unloading. He lifts those he can, drags or hauls those he cannot. He grunts with effort as he tips the corpse of a large man over the rim of the carrion-pit; it rolls down the slope and lands on the pile with a noise like a sow flop-wallowing in deep mud.

At last, the cart is emptied. The hungry gulls wheeling above voice their approval and impatience. The driver places the boy's cloak-wrapped body with the others, then returns to his seat and goads the ox back toward home.

When he is gone, it is time for me to domywork.

I descend among the dead. The rats and birds do not flee from my approach; their kind know me of old, and know that I am not here to interfere with their feeding. Indeed, the rats welcome me, because my scavenging helps clear the way for their own.

The rot-stench does not bother me. Nor does the unyielding rigor of flesh, and the clammy feel of skin moist with coagulated oozings. I do not cringe from gaped mouths where worms crawl, or from the maggots that writhe and teem in sockets where sharp beaks have plucked out the milky orbs of sightless eyes. When I find a she-rat has birthed a litter in the eviscerated hollow of a man's belly, I do not disturb the tiny creatures, naked, pink and squirming.

I pick up the man's dead hand in mine.

A large hand, tough, strong, powerful, well-calloused. The knuckles are scarred. A half-healed cut slices the base of the thumb.

The nails are very good.

Broad and thick, healthy, and long.

Not overly long, not protruding much beyond the tips of the fingers, but long just the same. Untrimmed for some while, several days at least.

Of course. As I had expected, and why I had come.

In times such as this, plague-times or other times of illness, disaster or despair, these little matters often go neglected. There are, folk think to themselves if they think of it at all, far more important matters to attend to. Trimming their finger- and toe-nails can wait. A day more or less, what difference would it make? Then they fall ill, and grow sicker, and die … and those who survive are in no fit state to attend to grooming the dead.

All the better for me, and for my work and purpose.

The tools of my trade, I wear on a ring at my belt. I have many of varying sizes and kinds. They clink and rattle as I move. Iron and silver, antler and tin, whale-ivory, wood, hammered brass and forged steel … from needle-fine pincers to sturdy gripping-tongs such that a blacksmith might use … my belt-ring of tools holds something for every occasion.

I choose the best tool for this, and begin as I always do, with a forefinger. I pry up the nail enough to wedge the bottom jaw underneath, then bear down with careful pressure until I have it in a sure and firm grasp.

Then I pull.

**

THE SHIELD-WALL

Dark earth underfoot, the grass matted, mud churned

Grim clouds burden the sky, the earls' banners wind-blown

Smoke and steam rise mingling with the fog of our breath

The stink of sweat and wet leather, the stamping of horses

Torches spit and sputter in a dawn-squall of cold rain

Across the chosen war-field, the enemy awaits us, our foes

We take our places, strong men and tall, shoulder-to-shoulder

Clad in mail-coats and fur cloaks, grim-faced beneath helms

Last night, at the ship-camps, safe and warm by the fires

We drank and we boasted as we readied our weapons

Now that anticipation turns to insidious dread

A hushed silence of unspoken, unspeakable fear

Soon, the horn-calls will sound, the armies advance

Soon, war-cries will be given, swords sing from their sheaths

Soon, weapons will strike, the battle-clangor will ring

Here is where, in the shield-wall, on the war-field of slaughter

Here is where men are made, or unmade, reputations decided

Earning fame and glory, or cowardice, dishonor and shame

With a crack and clatter, the shield-wall is formed

The sound a great rolling like Thor's own thunder

Shields set one to the next in a line overlapping

Hard round dragon's scales, the serpent's armor

Heavy lindenwood-made, iron-rimmed, iron-bossed

Covered with oxhides, and painted bold colors

We at the front lead the charge, voices raised in a roar

Others rush close behind us; the very ground shakes

A dense press of bodies; there is no turning back

We call on Thor's strength, Tyr's war-craft, Loki's cunning

Hoping only to win the wise All-Father's favor

It is kill or die for us, all or none, victory or Valhalla!

Long-handled axes, hooked heads like bird-beaks

To catch on shields' edges, dragging them down

Chests and bellies exposed to spear-points and arrows

Bright-edged bites of sword-blades and sharp steel

Piercing through mail-coats, through furs and leather

Slicing skin, shearing sinew, spilling red rivers of blood

The scarlet-stained earth strewn with injured and dead

Hacked and hewn, bones broken, guts wetly unraveled

Heads cleaved from neck-stumps, skulls split or crushed

Severed limbs twitch, hands still gripping sword-hilts

Amid pain-groans and screams come the pleading

As proud men forsake honor to beg for their lives

We were promised reputation, glory, and lasting fame

We were promised silver, war-plunder, ring-gifts of gold

As the shield-walls shatter beneath onslaughts of battle

We think of treasures more precious than any of those

Mothers and fathers, wives, daughters, and sons

But it is too late, far too late for such thoughts

Ravens have gathered, grey wolves wait in the west

First among carrion-pickers, hungriest to feast

Black wings rustle, white teeth shine, golden eyes gleam

They take no sides, they care not who wins the war-field

Craving only our deaths, the more corpse-meat the better

Oh, and they know they will feed well this day!