David L. Craddock writes fiction, nonfiction, and grocery lists. He is the author of the Gairden Chronicles series of fantasy novels for young adults, as well as numerous nonfiction books documenting videogame development and culture, including the bestselling Stay Awhile and Listen series, Shovel Knight by Boss Fight Books, and Long Live Mortal Kombat. Follow him online at www.DavidLCraddock.com, and on Twitter @davidlcraddock.

It is the Year 1994…

In North America, turn-based strategy games were trampled by flashier video games like Doom and Mortal Kombat. All but one: Sid Meier's Civilization, a game of conquest and megahit developed by Maryland-based MicroProse.

Over in southwest England, the producers at MicroProse UK aspired to design a tactical game that matched or exceeded the success of their American counterparts, who viewed the UK branch as nothing more than a support studio. Nearby, a bespectacled teenage boy toiled away on his home computer, dreaming of the day his programming aptitude would catch up to the epic campaigns unfolding across his imagination.

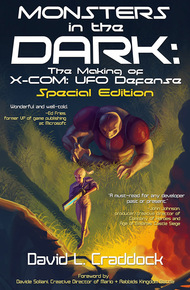

From his early experiments in board games to digital battlefields that lit up bestseller charts, Monsters in the Dark charts the career of legendary designer Julian Gollop through the creation of 1994's X-COM, a terrifying and terrifyingly deep wargame hailed as "the finest PC game" (IGN) and "a bona fide classic" (GameSpot).

Monsters in the Dark was a pleasure to write, but there was more content than I could justify packing into the book's main narrative. I'm a hoarder in terms of my writing: I cut words that need to go, but I never throw them away. Monsters in the Dark: Special Edition—which is only available as a digital book for this bundle—offers several interviews that expand on the roles many designers played on the original X-COM, and a lengthy interview of X-COM: Apocalypse, the third game in the series. – David L. Craddock

"Monsters in the Dark is an engaging history of not just X-COM, but of Julian Gollop's path to creating one of the cornerstones of strategy gaming."

– Soren Johnson, lead designer of Sid Meier's Civilization IV"Reading Monsters in the Dark was like traveling back in time to one of the great periods of PC game development. David not only tells the untold story of X-COM's development, but the incredible adventure its creators underwent to bring the game to life."

– Chris Taylor, creative director of Total Annihilation and Supreme Commander"When we see an amazing game, we rarely see the years of trial and error that came before it. I remember being blown away when I played X-COM, but until Monsters in the Dark, I didn't know about Rebelstar, Laser Squad, or any of Julian Gollop's other early works. The story is wonderful and well told, and I am so glad this piece of our history has been captured and preserved for us to enjoy."

– Ed Fries, former vice president of game publishing at Microsoft, and general manager of 1Up Ventures"X-COM was probably every developer's favorite strategy game from my generation. I must have played the demo—included on a 3.5-inch floppy disk that came with a PC gaming magazine—for more hours than I put into full games released these days. It still sits at the top of my list of my favorite games. Monsters in the Dark brings back memories of the intricacies and hurdles developers faced back in the earlier days of game development and highlights the incredible journey of an incredible game designer. It is a must-read for any developer past or present."

– John Johnson, producer/creative director of Company of Heroes and Age of Empires: Castle Siege, and CEO of Smoking Gun Interactive Inc.TEN-YEAR-OLD JULIAN GOLLOP scanned the packages arranged underneath the tree on Christmas morning. His eyes swept past too-small and too-large boxes until they latched onto a thin rectangle cocooned in brightly colored paper. Behind him, the adults stumbled into the room rubbing sleep from their eyes and gave the children permission to open gifts.

The kids exploded into motion, everyone rushing for one box or stocking. Julian went straight to the gift-wrapped rectangle. Hefting it, he smiled. Something rattled inside. Bits of plastic, perhaps small pencils and notepads. He could not say with certainty what the box contained, but its size and those telltale sounds amounted to his favorite holiday tradition. Every year, the Gollops rounded up Julian and his siblings to spend Christmas with their grandparents in Leeds, Northern England. Every year, Julian and his siblings expected one present of a certain type. Unless he was quite mistaken, Julian held that present in his hands.

"My father was very keen on games," says Gollop. "He liked to play all kinds. Bridge, canasta. Backgammon was a favorite game of his. He actually bought us a lot when I was around nine or ten. And not just the classics like Monopoly. He tried to buy something interesting every Christmas."

His brother and sister wore expectant looks as they spotted what he held. Their father leaned in to watch as they tore into the paper. At last, Julian held aloft a colorful box containing a board game. The lid depicted a towering castle crouched on a hill. Nazi guards prowled the grounds under an ominous sky, oblivious to the pair of frightened but determined POWs hiding nearby. Bold white letters spelled out Escape from Colditz, and it was unlike any board game Julian had seen. The menacing tableau contrasted starkly to the bright and colorful illustrations that adorned games aimed at children.

On that snowy Christmas morning, Escape from Colditz became a family affair. Julian, his father, his siblings, his mother, his grandfather, and others made up a team of eight. (His grandmother opted to sit out the game, preparing dinner so all of her soon-to-be-escapees would have sustenance following their desperate escape.) Together, the family worked out the rules. One player acted the part of security officer; the others assumed the roles of POWs. One of the prisoners was appointed escape officer, a coordinator charged with gathering equipment such as helmets and preparing to escape. The security officer monitored the prisoners to thwart escape attempts, such as by confiscating equipment and throwing conspirators in solitary confinement. All the while, the escape officer worked to free POWs within a tight time limit. Freeing two or more meant victory for the British soldiers, whereas all the security officer had to do was run down the clock.

The Gollops were not the first to escape the infamous German castle. That bleak honor goes to Airey Neave, the first British POW to break free of Colditz. Patrick "Pat" Robert Reid was another. An officer in the British Army, Reid was captured on May 27, 1940, alongside other members of the British Expeditionary Force by German soldiers and sent to Laufen Castle in Bavaria for imprisonment. Reid plotted escape within a week of arriving at the POW camp in June, his resolve so ironclad he believed he'd be home in time for Christmas.

For his first attempt, Reid connived with seven other prisoners to dig a tunnel from the prison basement to the outside. Over seven weeks, they carved out a twenty-four-foot passageway that led to a small shed. From there, they disguised themselves as women and made their way to Yugoslavia but were apprehended in Austria and returned to Laufen Castle, where the guards punished them with a month in solitary confinement and nothing but bread, water, and a bed of wooden boards.

After half a dozen foiled attempts, the German guards grew tired of Reid and his cohort and shipped them off to Colditz. To the Germans, imprisonment in Colditz was as good as a death sentence. They had occupied the castle since World War I, during which no POW escaped. Security was even tighter during WWII. According to Reid's memoir, guards outnumbered prisoners at all times, and at night, floodlights burned away shadows from every angle. The drop from cell windows to the ground measured at least one hundred feet. Sentries patrolled the area night and day, barbed wire coated fences, and the castle itself stood on a hill where the only way down was a drop of varying heights, most lethal.

Life inside Colditz was less harsh than its security measures suggested. Its commanders adhered to the terms of the Geneva Convention; prisoners spent their days reading, playing sports, and, in the case of Reid and many others, hatching escape plans.

Reid tried plot after plot. His first entailed teaming up with eleven other men to bribe a guard, only for the guard to take their money and snitch to his superiors. On another occasion, Reid and another soldier donned the uniforms of laborers and, using a saw smuggled into the castle through their network of conspirators, sawed through a barred window and descended into a sewer. They emerged on an outer lawn, where a forty-foot drop halted their progress.

Colditz wasn't as impregnable as the Germans liked to boast. Two factors worked against it: its sprawling size, which made it difficult to staff and operate around the clock, and its reputation. From 1933 until 1939, it held "undesirables" such as Jewish people and homosexuals. After six years, the Germans repurposed the castle as the final stop for Allied soldiers, many notorious for breaking out of other POW camps. Every prisoner was a Houdini of escaping castles, fortresses, and installations. For most, freedom was a matter of when, not if. Schemes ranged from duplicate keys to copies of maps to documents giving prisoners fake identities to pretending to be physically or mentally ill and getting transplanted to a medical facility. More elaborate plots entailed prisoners sewed into mattresses and tying bedsheets together to form ropes, which became a comical plot device in cartoons.

For Reid and other would-be escapees, the goal was to hit a home run, meaning an escape that took them out of Colditz and into Allied territory. On one occasion, Reid rounded third when he and a group of prisoners worked for seven weeks digging a tunnel that stretched twenty-four feet from the prison's basement to the adjoining shed of a house. They entered their tunnel in October and came out the other side but were captured in Austria and sentenced to a month of solitary confinement as punishment. Undeterred, he became what the prisoners referred to as an "Escape Officer" and helped others make bids for freedom. On October 14, 1942, Reid and several others swung for the fences by sneaking through the kitchens, crossing the yard, and descending into the cellar where they stripped off their clothes to climb nude up a cramped chimney and over a ten-foot-tall wall topped with barbed wire. On the other side, they slogged through sewers for eleven hours until they surfaced in a park and trekked for four days until reaching the neutral territory of Switzerland. Years later, Reid wrote two successful nonfiction memoirs and went on to co-design the board game based on his experiences.

The Gollops played Escape from Colditz for hours. Julian was as mesmerized by the theme and history that informed the adventure as he was the game's mechanics. Its rules and constituent parts were more complex than any game his dad had introduced him to, and the tense narrative made him feel like he was living someone else's life, part of a story instead of a bright-eyed boy sitting warm and comfortable at a kitchen table. After the rest of the family dispersed, Julian, his mind still spinning, found someone else willing to play other games. "Often I would play with just my brother and sister. I remember a game we had called Buccaneer, which was a board game with pirates."

JULIAN GOLLOP WAS born in India in 1965. When he was six, his father, who had built a career in banking, got a position in Sweden. The family remained there for two years before moving once again to the United Kingdom. Julian made and lost friends in each place. Although he missed them, he had his siblings and his father's proclivity for board and card games to anchor him.

Around age eleven, Julian's approach to games underwent a radical change. He loved chess until, after countless hours hunched over the black-and-white-checkered board, he discerned its fatal flaw. "The best players learn the best library of opening moves and sequences. That initial setup always being the same can make chess a bit boring."

Wanting to change things up, he examined the board one afternoon and realized that twisting it so players started in opposite corners exposed new tactical possibilities. "The pawns normally moved diagonally, but with my setup they could capture by moving straight, so their rules were reversed. I guess those were my earliest game mods. I was about six or seven when I did that. This was typical. I would try to either modify a game or try to build a game of my own based on what I played."

Questions that began with what if and how guided Julian from experiment to experiment. He went to the cupboard where old games gathered dust and raided their boxes for cards, plastic figures, dice, and other components. Then he mixed them together to create games of his own. His siblings enjoyed his makeshift games, but he hit a wall when his designs grew so big and bold that they called for over three players.

In 1974, the Gollops moved to Loughton, a town in southeast England just north of London. Julian and his younger brother, Nick, started school there in 1976, where they befriended two other brothers who shared their interests and their ages. "The two families each sent two boys to Davenant Foundation Grammar School in Loughton," says Andrew Greene. "I shared a class with Nick while Julian was in the same class as my elder brother, Simon."

The Gollops moved again two years later, but this time the sudden relocation worked out. Instead of journeying to another country, the family landed in Harlow, a nearby town where Andrew and Simon lived. "Pretty soon after we moved, we were running our Sunday morning game club," Nick recalls. "We used to play every Sunday: board games, RPGs like Dungeons & Dragons. That was something we did from 1980 and onward."

Occasionally, another mutual friend called Matthew Faupel made the pilgrimage to the Gollop household for the Sunday morning club. Andrew favored D&D, but the club played everything from card and board games to the sci-fi-themed pen-and-paper role-playing game Traveller, an adventure in which players engaged in interstellar combat, trading, and exploration; and DragonQuest, a fantasy RPG by Simulations Publications and the chief rival of TSR's D&D.

Julian absorbed each game's rules like a sponge. Once, he observed as Nick and a friend played Cobra: Game of the Normandy Breakout, another WWII-themed game in the vein of Escape from Castle Colditz, but much more intricate. Cobra unfolded across a huge map composed of hexes that held tiny cardboard pieces. "It helped me realize games could be more sophisticated," Julian remembers.

Years later at school, Julian joined a board games club where he learned even more about complex mechanics and designs. Standouts were Squad Leader, wherein players took command of soldiers and established defense posts; and Sniper!, which challenged players to carefully plot out their moves. Once he was old enough to get a job, Julian spent paychecks on games. His favorites were sci-fi and fantasy romps; they offered worlds to explore, like Escape from Colditz, only much more elaborate since they weren't rooted in reality. One of his favorites, Simulations Publications' Freedom in the Galaxy, reminded him of Star Wars. Players assumed the role of heroes in a space opera, and while the universe was massive, combat took place on smaller, more intimate stages.

"There were rebel and imperial forces massing against each other," Julian says. "The Empire controlled worlds. There was diplomacy involved. Basically, the game had this sense of the micro scale of the individual tactics going on, and the macro scale of managing an empire and its economics, productions, and military actions."

Julian's design ambitions blossomed as he tried more types of games. He divided a board into lanes where handcrafted miniature cars represented players. Each vehicle contained a tiny stick that players shifted from first, to second, to third gear. To move, players rolled dice and added their value to their vehicle's current gear. Rolling a four in third gear would move them ahead seven spaces, and so on. Just like in real races, going as fast as possible at all times guaranteed disaster. "Corners had maximum safe speeds, so if you ended up going faster into a corner than you should be, you spun off," Julian explains. "You had to decide how much risk you were taking with your gear selection. If you rolled a six and you were in third gear, and the maximum speed for the corner was seven, you'd spin off the track."

The game's mechanics produced a risk-versus-reward style of play that thrilled the other club members, but Julian devoted most of his time to the board. "It was elaborately drawn. I used paint to add a bit of color. I put a lot of effort into the physical components. It was time-consuming. I actually enjoyed creating boards and maps. I spent a lot of time making maps for all kinds of games, some of which were not very good and didn't get played very much."

Members of the Sunday morning game club volunteered as Julian's first and most eager testers. Some sessions went more smoothly than others. "Julian used to make up his own games, and invariably, when he was losing, he'd change the rules so he would win," says Nick. Many games lasted more than one Sunday morning but came to abrupt endings late at night when the family cat, who had a habit of gamboling through the house while the humans slept, rampaged across game boards like Godzilla attacking Tokyo.

In 1982, Julian made Diplomacy, an expansive strategy game that took place on a map of the world. Every country held an army, and Julian fashioned hundreds of tokens to represent the size of each army. Players resolved conflicts through battle or diplomacy. After several playtests, Julian concluded his combat system was much more fleshed-out than the diplomatic options. "The bad designs were probably the ones that were too complicated and ambitious," he admits. "The good ones were simpler."

One such simple game was inspired by the World Cup that the Gollops and virtually everyone else in England obsessed over while it was on. Julian modeled teams after every international club, assigning each a ranking in categories such as defense and midfield. A set of cards split the pitch into eight zones, and an arrow pointing to a zone represented the ball and its current direction. Players put down cards to move the ball up and down the pitch. "It moved quickly, so you could play a football match within about fifteen minutes," says Julian. "We played that with my brother and my cousin."

Time Lords, another of Julian's creations in 1982, blended simplicity and complexity. "There were no components apart from a piece of paper, a pencil, and an eraser. Each player had to have their own piece of paper, and there were some dice involved," Julian says.

One player, designated the game master, rolled dice and followed a set of rules to generate a universe spanning fifteen time zones and five planets. The other players explored zones and waged battles to determine who settled where and, more importantly, when. "You rolled dice to see how the civilizations grew and to see if you colonized another planet, to fight and resolve the war," Julian says.

Each player kept tabs of all fifteen time zones and five planets on a sheet of paper. As they rolled dice to travel to planets, the game master consulted dice and documents to inform them what they found at each location. With luck, they discovered a civilization whose people would share their history as far back as their time zone permitted them to remember it. Should that history include a war, players could travel back in time and alter history for themselves and every other player and race. "This would have to be marked on the game master's sheet, because the survivors got changed, so the game master updates the universe plan while each player only has their own view of the universe based on the time zones they've visited and the history they can extract from civilizations," Julian explains. "The winner survived and the loser was wiped out. It got a bit complicated to manage by hand."

Juggling Time Lords' many moving parts fell on the game master, who had to know what was going on in each time zone and on each planet to keep things running. "It's one of those games of hidden information. Each player has different information than the others; that's why a neutral referee or game master was required."

Two of Julian's creations stood out to Andrew Greene. One was Oertane/Unertane, a fantasy game set on an intricate map split between two hemispheres that players fought for control over. "Oertane/Unertane ended up in the dustbin for some silly reason, coffee spilt over it or something, I don't recall," Andrew says.

Andrew's other favorite was Wizard Wars. One player shuffled the deck and placed cards facedown near a rectangular board that functioned as a battlefield. Each player received a card that represented their wizard. As the game progressed, players drew cards from the facedown pile and cast the spells they described. "Many of the spells were creatures," explains Andrew, "and if your wizard cast a creature, its card was placed adjacent to him or her on the board. Your wizard card and accompanying army of creature cards would move around on the board and fight the other wizards."

Gaining a spell card didn't guarantee a successful casting. Spells could be chaotic or lawful, and a counter on the board showed how many spells of each type had been cast. Casting more lawful spells shifted the world's balance in that direction, resulting in a higher successful cast rate for other spells of that type. Inevitably, players would have more of one type than the other, making the war over which type prevailed a meta struggle.

When the club's members gushed over Wizard Wars, Julian endeavored to understand what specifically made it so engrossing. He drew several conclusions. First, it involved some randomness. Players never knew what spell they would draw, or whether it would be chaotic or lawful. Second, the rules were sophisticated enough to make for memorable battles but not so complex that no one could follow what was happening. Third, the combination of spells and spell types resulted in gameplay robust enough to ensure that, unlike chess, the game could be enjoyed without growing predictable. "From very early on, randomness can be used to make games interesting because it can present interesting situations to players, who then have to make interesting decisions for situations they haven't encountered before," says Julian. "That was a very early theme in my game design career."

Wizard Wars was fun in part because each session ended quickly yet left players satisfied. "They'd be over in ten minutes, so you could jump right into another one," he says. "If you lost one game, you'd say, 'Oh, well. Let's try another.' The consequence of losing is not so bad because you can always have another chance."

Those lessons dovetailed. "If you take a game such as Warhammer Fantasy Battle," he says, Games Workshop's popular wargame that became Warhammer and which involved lots of dice rolls early on, "some of those dice rolls are so crucial, and you spend hours setting the game up, and you spend hours playing it—you can have a bad dice roll that loses the game for you," Julian explains. One bad dice roll can leave players frustrated they spent so much time and energy setting up for nothing.

SUNDAY MORNING GAMING presented Julian with an outlet for his creativity. School afforded another. One afternoon, he stepped into his classroom to behold a boxy contraption at the back of the room. This, his teacher explained, was the Commodore PET, short for Personal Electronic Transactor. Some students regarded it as an overlarge calculator: nine-inch black-and-white monitor, cash register-like keyboard, and a tape deck for … what, exactly, Julian wondered?

Before long, a classmate inserted a tape and loaded a program titled Star Trek. A grid unfurled over the screen, and players piloted a miniature Enterprise ship, represented by an alphabet letter, across the galaxy. Julian's eyes nearly popped out of his head. "It was mostly text-based, very basic character-based graphics. It was a strategy-exploration game. That got me interested because it played a bit like a board game, but the computer was keeping certain things hidden from the player because the player had to explore."

Julian loved the idea of hiding information. It was possible in board and card games that demanded a game master to oversee proceedings rather than play, but human operators made mistakes or failed to manage complex games like Time Lords. Computers were different. Designers programmed in rules and left chores such as calculating outcomes to the machine, no pen and paper required.

The Commodore PET left Julian awestruck, but he could only use it at school. Then some friends purchased a Sharp MZ-80K, a personal computer released in 1983 that packaged monitor, keyboard, tape deck, and necessary guts like a CPU (central processing unit) and memory chips in a box-like chassis. Julian's friends set up the machine and immediately embarked on quests to program basic dungeon crawls, adventures where players explore gloomy cells and caves to fight monsters and loot treasure.

Their efforts were rudimentary, but Julian was infatuated with writing games. Unfortunately, PCs were pricey. First sold as a build-it-yourself kit in 1978 and sold throughout Japan, Sharp's MZ-80K came to Europe fully assembled but cost £600, roughly equivalent to $749.16.

"Then along came Sinclair with their ZX80 and ZX81," remembers Julian.

Originally called Science of Cambridge Ltd., Sinclair Research made waves across the United Kingdom when it rolled out the ZX80 in 1980. The first personal computer in the United Kingdom to sell for less than 100 pounds, it came in a kit priced at £79.95 that buyers had to solder together, or a readymade version for £99.95, and resembled a miniature cash register, only without a display. All parts were contained in a white plastic case topped with a blue membrane keyboard with the springiness and accuracy of a rubber glove. Still, the price was right.

Seventeen years old and gainfully employed in 1982, Julian found someone willing to part with a one-year-old Sinclair ZX80 (a name inspired by its Z80 processor) for the reasonable rate of 25 pounds. The seller confided he was planning to put the money toward Sinclair's new ZX81, but Julian was content with his new-to-him ZX80. It sported only one kilobyte of RAM, the memory needed to run software, but that was enough for him. As the ZX80 came without a display, users connected it to their television. At midnight that first night, Julian waited until everyone else went to bed, then lugged his prized machine downstairs, plugged it into the TV, and stayed up all night experimenting in BASIC.

"I did that for days on end," Julian says. "It wasn't too good because I didn't get much sleep, but I was just fascinated by programming. It was enormously appealing, the power to implement games."

Julian honed his skills over the next year. He advanced from BASIC to assembler, a tougher but more efficient programming language that enabled programmers to work more closely with a computer's hardware than BASIC's more comprehensible but less versatile commands. He quickly bumped into the machine's paltry RAM limit only to discover cartridge-like memory packs that plugged into the ZX80's expansion bays, increasing the RAM at his disposal. Their only drawback was the RAM pack wobble, a notorious failing known to hobbyists throughout the UK whereby the units were so top-heavy that they wobbled and slipped out. "If you even nudged it a fraction of a millimeter, the pack would come loose and cause the machine to crash."

The wobble curbed his programming sprints. Saving his code to a cassette, the only storage available, took several minutes. If the pack wobbled, the computer crashed, and Julian lost his progress. After yet another crash, he found a big piece of cardboard and taped it to the pack.

Upon finishing secondary school (equivalent to high school in the United States), Julian retired his ZX80 and upgraded to a ZX Spectrum 48K, or ZX-48K. Here at last was a computer that measured up to his lofty aspirations: eight-color, high-resolution display capabilities; 3.54-megahertz processor; a sleeker design and black coloring with another membrane keyboard; and a staggering 48 kilobytes of RAM, no wobbling add-on required.

Aware that the ZX line had sold well because of its competitive pricing, Sinclair kept the Spectrum line affordable by slashing pricey features such as a flat-screen display. Even so, the ZX-48K was a huge upgrade for Julian. It also marked the formal beginning of his life's work.

"That's when I started to work on games. At that stage, I was obsessed with computers. I just thought they had such awesome potential."