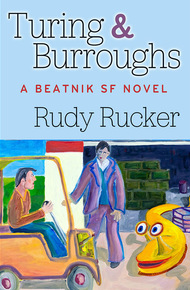

Rudy Rucker has written forty books, both pop science and SF novels in the cyberpunk and transreal styles. He received Philip K. Dick awards for his Software and Wetware. He worked as a professor of computer science in Silicon Valley. He paints works relating to his tales. His stories can be read online his Complete Stories webpage. His for coming novel Juicy Ghosts is about telepathy, immortality, and assassinating an evil, insane President who has stolen an election. Rudy blogs at www.rudyrucker.com/blog

What if Alan Turing, founder of the modern computer age, escaped assassination by the secret service to become the lover of Beat author William Burroughs? What if they mutated into giant shapeshifting slugs, fled the FBI, raised Burroughs's wife from the dead, and tweaked the H-bombs of Los Alamos? A wild beatnik adventure, compulsively readable, hysterically funny, with insane warps and twists—and a bad attitude throughout.

"Rucker's novels have an angle of attack reminiscent of the Thomas Pynchon of Gravity's Rainbow and the Terry Southern of The Magic Christian. Turing & Burroughs is all of that and more. Much more. Turing & Burroughs is centrally the story of an imaginary gay affair between William Burroughs and Alan Turing. Rucker being Rucker, this central story line is not even half the bizarre, fascinating, scientific, sexual, and historical content of this delightfully humorous yet somehow thematically serious novel."

– Norman Spinrad, Asimov’s SF Magazine"A delightful alternative history romp set in the middle of the 1950s. Rucker immerses the reader in the beat milieu, with the added twist that here they really are pod people, and loving it. … This novel engages the reader to such an extent that it's easy to overlook the extensive research that went into making it authentic, not just superficially, but in depth."

– John Walker, review in Fourmilog"Rucker's "Beatnik SF Novel" deftly combines historic characters and wild flights of imagination in a spin-off of our world's history. … Rudy Rucker has produced an SFnal tour de force. … The prose in Turing & Burroughs can flow like a drug-stoked dream."

– Faren Miller, review in Locus MagazineWhen Alan Turing reached Tangier in June, 1954, the city's whitewashed lanes and towers seemed a maze of joy. He was elated with his escape from the shadowy agents who'd tried to assassinate him. And glad to leave the tedious, pawky computing machines of Manchester. He rented a comfortably furnished apartment and hid his money beneath a floorboard.

For now, Alan was free to do as he pleased—perhaps to idle, perhaps to push further with his startling new work on the chemical keys to biological morphogenesis. If he could fully fathom how Nature grows her knobby, gnarly forms, then he might well complete his lifelong quest to build a mind, to create a purely logical sentience by whom he could, at last, be understood.

He found that he loved Tangier on a visceral level. Every morning, Alan would take a long run on the empty beaches—the locals had little interest in the seaside. The quality of the light was uplifting. The muezzin calls to prayer were like intricately encrypted signals from a higher mind. And the cheeky street-boys of Tangier were a visual delight. For Alan, the Casbah was like a holiday fair with sweets at every turn—although, as yet, he hadn't quite dared to sample the boys. He was still in some fear of hidden enemies.

Seeking out fellow expatriates, he encountered the louche international café society of Tangier. At home, he'd rarely hit it off with mannered aesthetes, but in this odd backwater, everyone was hungry for companionship.

In his first month, Alan often spent the evenings at the Café Central in the Socco Chico square, enjoying the free-wheeling euphoria, the cognac, the mint tea and the kief. A dissipated Oxford poet named Brian Howard would hold forth on beauty, and then William Burroughs, a sexy, sardonic American of Alan's age, would send the group into gales of laughter with his scandalous routines. Alan noticed that amid the expatriates' merry intimacy there was no stigma in being homosexual.

One night the camaraderie loosened Alan's tongue to the point where he bragged to his raffish companions that he wasn't really the man whose name stood in his Greek passport.

"I'm not Zeno Metakides," Alan announced to the ring of smirking expats, his voice hoarsened by kief. "I only wear his face. In reality I'm a top-drawer mathematician who cracked the Hun's cryptographic codes. I won the war, don't you know—and now the Queen's mandarins want to rub me out."

The next morning Alan awoke with a start of horror. He must be suicidal, to be spilling his secrets to foppish wastrels who'd cut him cold, were they all back in London. He avoided the cafés from then on, going for his long runs along the sea in the mornings, visiting the market, and resuming his researches on computational morphogenesis.