Mary Turzillo loves cats and story-telling. Her "Mars Is No Place for Children" won a 1999 Nebula, and her Lovers & Killers won the 2013 Elgin Award. Sweet Poison, with Marge Simon, was a Stoker finalist and Elgin winner. Mary has been a British SF Association, Pushcart, Stoker, Dwarf Stars, and Rhysling finalist. Her recent books are Mars Girls (Apex, 2017) and Bonsai Babies (Omnium Gatherum, 2016). She fenced foil for the US at Veteran World Championships in Germany, 2016. She lives in Ohio, with scientist-poet-fencer Geoffrey Landis, plus Scaramouche, Samurai, Azrael, and Tyrael, the last four of whom appear to be cats.

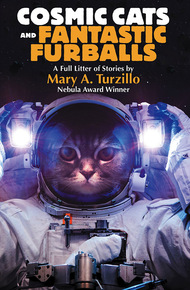

Curl up with a cat and a book. A full litter of stories—science fiction, fantasy, and mystery—all cats, every page.

A dying pet gets a new life through cybernetics—but will his humans accept a robocat?

Defrosted kittens run amok.

Chocolate kitties from Mars change from delicious treats to something a little different.

A Siamese detective fingers—or paws—a burglar. An alien furball lands on a cat-hater's doorstop.

A kitten's gift to the Christ child gets rejected, but that's not the end of this cat's journey.

A sphynx pussyfoots through a wormhole and finds his soulmate on the other side, narrowly escaping death.

A fisherman crosses a tiger kami and is transformed into a legend.

Angels dye a kitten purple and give it wings, but even those enhancements do not serve it well when it plunges to Earth in the path of a speeding eighteen wheeler.

And, in a Nebula nominated story, an extinct cat is revived from ancient fossil material and innocently rampages through a rural Ohio township.

A fun page-turner for fans of felines!

Steak Tartare and the Cats of Gari Babakin Station

Earthlings were coming to attack the cats this very afternoon. And where was Benoît?

Had she really considered licking his earlobe while he was reporting on the new cheese flavonoids? As if he were a surly tomcat, like this handsome furball now rubbing her legs?

Ah, Lucile, she thought, so

impulsive we are! The boy's not all that sexy; he never combs his hair or gets it cut, or even washes it often.

He had a certain something, though. Think how he lashed out at the Earth inspectors who came through a year ago trying to murder the feral cats in tunnel M. The inspectors wanted to vent that corridor and let the cats die of decompression. Benoît put them in their place.

Those Earth people! They need cats. Cats to sleep with, to feed, to pet, to tease with bits of string, to get a little rough with and wind up with a bitten finger or a scratched cheek. That would rearrange their psychic furniture.

Benoît used to say, "They have cats on Earth, too, so what the hell's their problem?"

But not cats like those of Gari Babakin Station.

Where was Benoît? As Supervisor of Flavor Engineering and the mayor's third in command, he was supposed to greet them so she could make a late, more impressive entrance.

A message came in that a rocketplane had arrived from Borealopolis carrying Terran supervisors.

Providentially, Benoît slunk in just then, running fingers through his greasy hair. He had been trying to grow a beard, and looked endearingly like an adolescent ferret.

"They're here," Lucile said levelly. "And me in this nasty old jumpsuit! At least I put on perfume this morning." She swung around to Benoît. "You were supposed to greet them."

"I didn't think they'd follow through on their threat," Benoît said. He picked up the cat that had been pestering Lucile and scratched between its ears. At least she thought it was the same cat. All the cats looked the same, small polydactyl tabbies in varying shades of dark gray, with pink noses, all descended from the same pregnant queen that somebody smuggled into Gari Babakin Station twenty Mars years before.

"It's about the cats."

"Oh, yeah. That. They said some dumb thing about a parasite or virus. I thought they were talking about crabs."

"Benoît!" she hissed. "They are not sending a delegation from Earth or even from Borealopolis to stop an epidemic of crab lice." She clawed through her desk drawer for her makeup kit, but found only a purple lace garter belt she had misplaced.

"So? Why do they always have to pick on us?"

Benoît exasperated her. He got more adolescent every day. He had a PhD in xenonutrition, for heaven's sake!

No, it wouldn't be worth seducing him, even if he was one of the few non-disgusting men on the station she hadn't bedded. "Listen, Benoît, they're coming through the front airlock. Could you entertain them? I have to go back to my apartment and change." What was in her closet? The red frock with the keyhole above the derriere. Perfect.

#

When she got back, nicely turned out in the black faux tux since the red frock had a bigarade sauce stain near the plunge of the neckline, she found Benoît and three strangers in the reception room off the main airlock. Benoît's hands were jammed in his pockets, his eyes narrowed with paranoid hostility. The three strangers—two dowdy-looking women and a slender youngish man with chopped-off hair and depilatory burns on his cheeks—were still in environment suits, shrinking away from the clowder of cats weaving in and around their legs.

The man pulled off his glove, strode forward to shake hands with Lucile, faltered as if he had changed his mind about touching her, then finally seemed to conquer his squeamishness and held his hand out like a Ping-Pong paddle. "I'm Godfrey Worcester," he said. "You're the head of the station? Martialle Lafayette?" He used the feminine of the Martian formal title for citizen.

Lucile took his hand and held it in both of hers. "No, no, Jean-Marie took a personal day. I'm in charge in his absence." What a shame Jean-Marie liked his wine so much, especially before lunch.

"Jean-Marie? A man? We really need to talk to Martial Lafayette." He switched to the masculine form. "You would be?"

"I would be Lucile Raoul. I'll send for Jean-Marie." She gazed into Godfrey's hazel eyes. He was a handsome, trim fellow despite the fact that his barber apparently hated him. She liked these naive types.

She turned to the two women. "May I take your suits? Your suitliners? We have some chic little dusters you can change into while you're in the station." She tried not to roll her eyes. Both women apparently had been victimized by the same barber as Godfrey, and she shuddered to think what they wore under their suitliners. Neither of them seemed to have the imagination to go naked underneath, although you never could tell.

Benoît sprang to attention. "I know what you're after, and we will resist to the death."

Lucile let go of Godfrey's hand and went to Benoît. "Benoît, dear, let these nice people have their say. But first, may I offer coffee and a pastry?"

"Where do you get real coffee?" asked the frumpier of the two women suspiciously.

"But my dear, we didn't get it. We manufacture it. Alain, our head molecular gastronomist, is just a genius with esters."

"He's the one that concocted the wine you sent us?" the tall woman asked. She was wriggling out of her suit, revealing a suitliner in a ghastly shade of pink that she apparently thought she could pass off as station day-wear. Lucile tried not to look.

"No, no, we have a special vigneron. But—"

Benoît interrupted. "We won't reveal his name. Your goons will kidnap him and lock him up in some forced labor laboratory."

Lucile looked daggers at Benoît. His eyes flashed, but he shut up.

#

Lucile escorted the trio (their clumsy gait in Mars gravity betrayed their recent arrival from Earth) to a patisserie on the upper level. The proprietor had coaxed a container of violets into bloom in the center of the room, under the mirror-maze skylight. The air smelled of cinnamon, coffee, and butter.

"Where's this Jean-Marie Lafayette?" the taller woman asked. Dr. Kermilda Wrothe was her name, Lucile had managed to find out. The shorter woman, who resembled a starved gerbil, was Dr. Hilda Wriothesley. "We can't be wasting time. This is a matter of public health."

Just then, two of the station cats—both wore purple bows around their necks, so Lucile concluded they belonged to the proprietor—started fighting, snarling, hissing, shrieking. The larger cat was apparently trying to mount the smaller, or maybe it was the other way around.

"I sent a message to his apartment. He'll be here as soon as he wakes up. Monsieur, may we have coffee all round, and a tray of your pastries?"

The coffee and pastries arrived and the three strangers eyed them with suspicion and desire.

Benoît said, "You can just forget it. You can't make us kill the cats. They are our soul."

Godfrey sat up straighter and said, "Oh, come now. Not only are you overrun with cats, but you are all infected with Toxoplasma gondii, and it's destroying your personalities as well as probably causing birth defects."

Benoît jumped up and leaned over the table, nose to nose with Godfrey. "That's slander, punk. First of all, impugning our personalities is tantamount to admitting that you want to enslave everybody on this station, take our proprietary secrets for wine and cheese making, and then wipe us out. Second, no child has been born on this station for over fifteen Mars years."

It was the longest speech Benoît had made in the entire time Lucile had known him. She stirred her coffee and sipped daintily. Under the table, she drove her spike heel into Benoît's instep.

He turned to her, bewildered.

"What Benoît is saying," she purred, "is that we are well aware of the issues involved in Toxoplasma gondii infection, but we feel that you are, shall we say, trying to impose your cultural values on us. I mean, as non-toxoplasmotic people."

Hilda spoke up for the first time. "Surely you can't mean that you enjoy the cultural values, as you call them, of being infected by a parasite?"

"That's exactly what she means, you constipated hag!" Benoît half rose and yelled in her face.

Lucile kicked him again, harder, and he sat down, deflated. She continued, "We prefer to think of Toxoplasma gondii as a kind of beneficial symbiont."

"That is just outrageous!" said Dr. Hilda Wriothesley. "We've monitored your communications. Analysis shows that your men are paranoid, poorly organized, and brain-damaged, while your women are—well, they're—"

"Stylish and attractive to the opposite sex?" Lucile purred. Her gaze traveled over the gaudy, shapeless coveralls the two women wore.

Godfrey stared at her, openmouthed.

She flicked a smile at him, as if they shared a delicious secret.

Godfrey cleared his throat, then started up a presentation from his finger computer, flashing the slides on the tabletop. "Top scientists at Utopia University have developed a virus which kills Toxoplasma gondii while leaving the host unharmed. It works very well with humans, and while there have been minor side effects in feline subjects, we feel that it is a viable solution to a public health problem that could otherwise spread beyond Gari Babakin Station and infect all of Mars."

She let him drone on. She'd heard it all before, but she enjoyed watching his lips. She'd love to get better acquainted with him, but there might not be time before he had to return to Borealopolis. And then there was the problem of Hilda and Kermilda. Entrusting them to the tender mercies of Benoît was out of the question, but maybe when Jean-Marie woke up, he could take them on a tour of the greenhouse vineyards.

When Godfrey turned off the presentation, she put her hand lightly on his wrist. "Dr. Worcester—Godfrey—you do make a point, but we really like our lifestyle here. We could put this to a referendum—but would we force the cure on people who didn't want it?" She had revolting images of herself dressed as badly as these two victims of the cult of sensible shoes.

"You're willing to forgo the joys of parenthood, then? True, you've enforced strict birth control via the air supply, but surely your women must yearn at times for motherhood."

She sighed. Now he was playing to her weak side. A charming little baby girl, to dress in pretty little frocks, to feed greenhouse strawberries and tidbits of pastry, to teach charming songs, to love, love, love—but Toxoplasma gondii could cause great harm to fetuses: blindness and encephalitis.

However, on the bright side, she was already seropositive with the parasite, so she reasoned that her future offspring was safe. She was sure. Almost. She need only protect the child from infection until its immune system was fully developed. She could surely arrange that.

However, she hadn't yet met anyone she trusted to father her adorable child. She smiled lingeringly at Godfrey, and he flushed slightly.

Benoît's eyes flicked warily from her to Godfrey. "You part of that Mars-needs-more-babies movement?"

Godfrey's lips turned white and pinched. "No, no! We just feel—well, your station's culture has—problems conforming to the overall community values of Martian life."

"And our culture deviates how?"

Hilda threw up her hands. "People sleeping until midday! Bed-hopping! Nobody cares whether the filing and maintenance are done properly, or at all! Not meeting planet-wide quotas! You put it kindly by saying the parasite makes women more gregarious, albeit at the expense of domestic tranquility, but the men, the men here—"

"Are more original," Lucile said.

"They have intellectual deficits!" Kermilda barked.

"They think outside the box. They aren't intimidated by common so-called wisdom," Lucile continued smoothly.

"Like cats," said Benoît.

And, in fact, the two squabbling cats were now a picture of cuddly affection, purple ribbons and all, under a table grooming each other. Lucile suppressed a smile, imagining Hilda and Kermilda doing the same. Except of course they would be repulsed by saliva.

She returned her gaze to them. "Gari Babakin Station excels in contributing innovative ideas to the greater Martian civilization."

Godfrey made a show of turning off his data ring. "Well, none of this means anything at all, because NutriTopia Ares, which I must remind you owns every molecule in this station, has authorized me to release the virus as soon as feasible."

He and the two women drained the last drops of their coffee, got up, and left.

After a stunned moment, Benoît leaned over. "Did they already release the virus, without talking to Jean-Marie?"

Lucile glanced at his worried face. "That's not the question you should be asking, Benoît. The issue is, what will the virus do?"

"Turn us into impotent zombies."

She sighed. "I don't know if the personality effects can be reversed once the Toxoplasma gondii takes root. The question is whether their virus will kill the cats. Or," she added, "us."

#

Lucile was not as worried as she sounded. In fact, she wasn't even sure the scientists of NutriTopia Ares had a technology to destroy Toxoplasma gondii oocysts. Previous attempts, with sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine-type drugs, had been unsuccessful, although they had certainly made enough people nauseated and anemic. Still—

Everybody at Gari Babakin Station knew their universal toxoplasmosis infection came from an infected pregnant cat named MiguetMuguet. They even accepted the evidence that it might raise women's intelligence and lower men's.

There had been a problem with the water filtration system early on in the history of the station, and unfortunately it kept getting recontaminated by oocysts shed either by cats or by humans. The citizens had stopped trying to fight it.

Lucile had arrived at the station at the age of eight, and stayed when her parents left to go back to Earth when she was twenty-three. She had no idea what she'd be like if she'd never ingested the oocysts, but she did, if she were honest, think herself more attractive and better dressed than the average Martialle.

As to Benoît, when he had arrived at the station three years ago, he had been meticulous in his habits. He kept tidy notebooks of his experiments in food engineering and wore his hair and mustache short and neat. He had planned to stay only a Martian summer, but somehow he'd abandoned his original plans. His neatness quotient had gone all to hell after four months; Lucile remembered him suffering a brief episode of the flu, and afterward his attention span went south.

He had known about the toxoplasmosis infection before he'd come; he'd thought he'd be immune. He had no logical reason for believing this, so no surprise that he wasn't.

NutriTopia officials were saying infected people were almost three times as apt to get into a work-related accident, and schizophrenia, hitherto unknown on Mars, was making a comeback as a result of the infection.

The other issue had to do with the need for Martian population growth. Not only were toxoplasmosis-infected women endangering their future offspring's health, they statistically doubled or tripled their chances of bearing a boy rather than a girl.

Lucile suggested this might be NutriTopia's hidden agenda. Because of early immigration practices (only postmenopausal or infertile women were allowed in the initial immigration, due to fears of genetic damage to developing infants), men outnumbered women. A disease that perpetuated that ratio would be unwelcome to the corporations that ruled Mars. That included NutriTopia Ares, which, as Godfrey had pointed out, owned every molecule of Gari Babakin. Mars needs babies. NutriTopia wants more workers.

Life, Lucile believed, was too short to dance with stupid guys, but intelligence was in the eye of the beholder, and she found the infected men of Gari Babakin—Benoît in particular—amusing, if not father-of-her-future-child material.

Of course she was careful not to override the station's contraceptive measures. She didn't want to hurt her theoretical future child.

#

Godfrey congratulated himself. He had been careful not to take a chance with any of the pastries or cheeses, although they smelled and looked divine. The coffee was hot, so that wasn't a danger, and wine was okay because the oocysts couldn't survive in alcohol.

At least they hadn't offered him any of that raw meat dish, that steak tartare made of hamster meat! How could they—

Headquarters had given Drs. Wrothe and Wriothesley and him very particular instructions about releasing the virus. He was to shake hands with the head elected official, this Jean-Marie Lafayette. Lafayette, his team had discovered, was linked by less than five degrees of separation to every single person on Gari Babakin Station. The virus had been engineered to outlive at least three hand-washings.

Hilda and Kermilda were also to shake hands with as many people as possible, but it seemed the uptight women scientists had been afraid of being infected by the parasite.

He would have to speak to them.

It would work anyway. He had anointed several railings and door handles around that pastry shop and the airlock.

Ah, my my, this Lucile Raoul was a charmer. He had no doubt she was even closer than five degrees of separation from most of the station. He regretted having to return home so precipitously. Oh, to match wits with her!

He also regretted not being able to sample the cheese and pastry. Gari Babakin cuisine was considered exquisite. Their exports to the rest of Mars were irradiated to kill off the oocysts, but two problems remained: one, Martian health officials feared that particularly robust oocysts might live through the irradiation, and the descendants would be harder to kill, thus infecting the entire planet with an unstoppable plague.

Second, the irradiation killed some of the flavor. Godfrey knew this not because he had personally tried a comparison taste test, but because a food scientist from Utopia had done so several Mars years ago, and swore there was no comparison.

That food scientist, one Fred Remaura, had lived in quarantine until recently, when he had been the human test subject for the virus that killed the parasite.

Now, profit motive drove Godfrey's supervisors to sanitize Gari Babakin so that their products would be safe without the flavor-dulling irradiation.

Those little jam tarts—the unaltered fragrance of butter and raspberry jam. And that Rocamadour cheese—yes, yes, very stinky, but what a seductive stink!

Maybe the cheese had some overtones of human sex pheromones.

He smiled at Hilda Wriothesley, but she only shuddered and said, "That woman is a human sewer."

#

Jean-Marie Lafayette lumbered around the mayor's office, blundering into cabinets and knocking stacks of files off display modules. Every third lap he would haul up in front of Lucile and say, "Do you feel any different? Do I look different?"

"Jean-Marie, just check your biometrics. I don't know if they've even released the virus yet. I don't think we'll know until it's much too late."

"Filthy tight-asses," Benoît was curled in a fetal position in the mayor's desk chair. "They've singled us out for destruction."

Lucile went to him. "Benoît, be wise, poor baby. They are misguided, but they tested the virus on humans, so the damage will probably be minimal. And look at the bright side. Maybe you'll be able to remember the multiplication tables again."

Benoît sprang out of his chair at her, but she smirked her "gotcha" smirk.

Jean-Marie was accessing some database he had suddenly remembered.

"Jean-Marie, darling, turn on your monitor so we can see too."

Jean-Marie tongued on his projector. A scientific paper from some long-forgotten minor Terran journal projected against the wall above the office door.

"Antivirals!" She clasped Jean-Marie's arm joyfully. "But where can we get them?"

Jean-Marie grinned. "Pascal LeBoeuf, our vigneron extraordinaire, my little cabbage."

#

Hilda tucked her pesticide spray into a pocket in her environment suit and polished the faceplate of her helmet. Godfrey could tell that she was nervous about the passenger cabin in the rocketplane. She preferred to keep her environment suit inflated and her helmet on when she was not inside a clean hab. Her work with infectious diseases had made her paranoid. She hunched in one corner of the cabin, a rodent-like figure of terror, and not touching anything, not even sitting down.

Kermilda, in contrast, believed the best defense was a strong offense, so she had loaded up on so many micronutrients that her breath and scalp emitted a yeasty, alcoholic scent. "They'll figure out right away what we did."

"I don't think so," said Godfrey. "They'll know we started the virus, but they won't know how it's propagated. It won't wash off those yokels' hands, and anyway, I inoculated every surface I encountered in that hab, starting with the mayor's office and even the airlock. And I added a thin layer of the protein substrate."

"Yes," said Kermilda, "but they may try to develop an antiviral."

"That would take time, and by the time they succeed, let's hope they'll come to their senses and realize we have only their greater good in mind." Godfrey contemplated a return to Gari Babakin once this whole thing had blown over. He'd love to meet more of the natives. Especially if any were like that Lucile Raoul. He could write a paper on the personality differences wrought by curing the population of toxoplasmosis infestation. What would Lucile be like when relieved of her parasitic burden? Would she be just as convivial, but not as manipulative?

Hilda spoke for the first time. "I wonder how they'll react when the cats start dying."

#

Lucile found the half-grown kitten under her workstation when she came in for work. It was cold and limp. She flinched, then cuddled it to her chest. Poor little thing! Poor, poor kitten!

This crystalized her fear that the cats were going to die, all of them. Dozens of pet cats on Gari Babakin Station had already sickened with a mysterious wasting illness, and the feral colony was reduced to a quarter of its former size.

She had been afraid this would happen ever since Godfrey's visit. Jean-Marie had called a town meeting of the entire station. It was the first time that the entire male population had turned up, many of them sober. Everybody knew Godfrey's team would release a virus to kill the oocysts, but there was no way of knowing what method they'd use to propagate it. The water supply had been examined for new viruses, as it was well known that phage virus particles thrive in Earthly sea water, but since Gari Babakin had so few microbiologists who were trained in other than food synthesis, it was like looking for a needle in a haystack.

She threw open the door of Jean-Marie's office. "We've got to take action. They're killing our cats, our souls!"

Jean-Marie rose heavily to his feet and lumbered over to her. He wrapped ham-like arms around her and breathed wine breath into her face. "I know, I know, my dear, but what, what more can we do? We're working on the antivirals—"

"Let me call the head of their sanitation team, that half-scalped idiot that came out here in the spring."

"Is he still on Mars?"

"Of course he is! Earth transport hasn't left Equatorial City since he and his she-goons were here. Anyway, he seems the type that wants to stay on Mars. Become a Martian."

Jean-Marie sighed. "But not a Martian in the truest sense, with the advanced culture provided by our oocyst friends."

"No. Not in the purest sense."

Benoît appeared in the doorway. He was wearing a clean shirt and hadn't crashed the station computer system in weeks. Was the phage destroying his toxoplasmosis infection, converting him back into a straight-arrow Martian?

Benoît said, "You might try seducing him."

"Surely he's not that stupid!"

Benoît stroked his mustache.

#

Lucile spent more time gazing into Bon Bon's inscrutable eyes, as if the sleek affectionate cat might have answers. A weekly lab test of her own toxoplasmosis status showed that she remained seropositive. The immune factors might just remain in her blood after the cysts were gone. But she thought not. Her bills for package delivery service and droplet manufacturing betrayed her continued interest in exotic lingerie. No, she hadn't started any new love affairs since the fateful day Godfrey and his hagfish entourage had arrived, but she had been busy. Anyway, her next project was Benoît.

Or was it?

Benoît would make an interesting playmate. He would need lots of fixing up, but toxoplasmosis-positive women liked that sort of thing. Of course, toxoplasmotic women also got bored easily.

She needed more of a challenge. Terrans were certainly not immune to the charms of women with toxoplasmic toxoplasmosis infections; this was well known. Many of the station women had a good laugh when one of them seduced another male into coming to the station on the sheer expectation of meeting the famed Gari Babakin sex kittens.

This particular challenge might save the station.

She put through the call.

Dr. Godfrey Worcester, NutriTopia Ares Project Manager for Toxoplasma gondii Remediation, was in fact still on Mars, at Utopia Station. And, his expression told her, even on her tiny screen, that he was both lonely and shy, but too damned dutiful to admit it to himself.

"Do I have the honor of speaking to the too-young-to-be-so-distinguished Dr. Godfrey Worcester? The scientist who developed the anti-toxoplasma virus?"

"Martialle Raoul, good sol," he said. He sounded courteous, but nervous. As he should be.

She made her voice soft and breathy, as if afraid she might wet her pants in admiration. "I have been thinking of you ever since you left us that day. We had so much to talk about."

He brightened. "I was actually hoping to see you again, Martialle Raoul—"

She method-acted her face into an expression of fetching grief, combined with vixenish fury. "My naughty doctor," she said in low, thrilling voice, "are you aware that you're killing our little kitties?"

He wilted like a failed erection. "We—uh, we considered there might be side effects with the cats. But surely not all—"

"Seventy percent! That includes Aristide Brewpub, the tom cherished by our mayor. Aristide died in agony a week after your visit. Autopsy shows kidney and heart failure, caused by the sudden death of the oocysts that the cat coexisted with." Actually, Aristide was perfectly well, but several other pet cats had died, and she figured Godfrey would be more appalled if he thought he'd killed the mayor's cat.

"There's nothing—uh, our own feline subjects tolerated the phage very well—"

She closed her eyes slowly, as if infinitely offended.

He blurted, "Are you experiencing any discomfort? I mean personally? I could come to the station and examine you. I'm a physician, you know. I don't want you to feel in peril with this perfectly safe treatment."

"Don't you understand, my dear bad, bad doctor? We love our cats. They are, how shall I say? The soul of our culture."

"But some of them are running around without masters, infesting your vacant tunnels—"

"You mean the feral cat community?" She blinked slowly at him. "On Earth, I believe there are actually more wild animals than domestic. We have reproduced that condition in miniature here in Gari Babakin." She leaned forward, pursed her lips. "I have an idea. I think you should come, as my guest of course, and experience firsthand this culture your corporate masters condemn."

Godfrey blanched. "You mean allow myself to be infected with toxoplasmosis? I'm afraid that's out of the—"

"But not at all! Your virus has wiped out the oocysts. The death of all our sweet pusskins shows that to be true. Come, you can stay in our charming little guesthouse. You'll be perfectly safe. Or with me, if you like."

Surely, he's not that stupid.

But he was nodding yes. Eagerly.

#

Godfrey's head was spinning when he turned off the call. She wanted to see him. Of course his motive was entirely scientific. He wanted to check the progress of the cure. Were the personality changes going to be obvious? His team had been monitoring internal and external communications from Gari Babakin for seven years. Text analysis, algorithm driven, had demonstrated marked deviation from normalcy. But he had actually met three victims of the disease: the mayor Jean-Marie Lafayette; Benoît Bussy, the mayor's research liaison; and of course the mayor's interesting assistant, Lucile.

He would be able to see firsthand if her personality had changed. Had she become less obsessed with fashion and personal appearance? That outfit she was wearing the sol he had been there—provocative, in a way he couldn't describe. Was she less effusive? Most of all, had she been cured of that regrettable promiscuity suggested by her secret smile?

The cure for promiscuity was without question the best feature of the virus cure. Except maybe for saving infants from blindness and encephalitis. And yet! She was interested in him; he could see from the look in her violet eyes that she wanted to see him. Perhaps—

He wasn't interested in romancing an experimental subject. Of course not.

He just wanted to see how the treatment (don't call it an experiment!) had turned out.

From ground level.

Of course if she and he decided to see each other socially, after the experiment was over—

The danger of becoming infected with toxoplasmosis was vanishingly small now, according to the computer model of how his virus cure had spread. And if he did become infected, he could just use the virus cure on himself.

A rocketplane was scheduled to go to Gari Babakin on Thursday. He would be aboard.

Plenty of time for him to make an appointment with his barber.

#

Lucile liked scientists. Since they spent most of their time with their eyes glued to a microscope or a computer output, they lacked the social lubrication of the public servants in the circles she moved in. Scientists were often charmingly direct. Unsophisticated, in the sense of lacking sophistry. She wasn't sure where this would go, but it would be no great chore flirting with Godfrey until she got whatever information she could out of him.

This time, she flinched inwardly when he took off his helmet. His scalp showed through in two places where the barber had apparently not been paying attention. But his eager smile, along with his scent of clean sweat, melted her heart.

"Now," he said, "let's discuss this issue with the feline side effects."

She took his helmet from him, helped him with the fasteners on his suit. "Where are your two associates, by the way?"

"They had other commitments."

Lucile repressed a smile. But of course. He hadn't even told them he was coming.

#

Less than twenty-four and a half hours later, they were in Lucile's bed, eating foie gras that Étienne Bergere had grown from duck liver cells. Lucile was always hungry after she consummated a seduction.

"You are not going back to the guest house tonight," she told him as he licked the last morsels off her fingers. "I can order breakfast in tomorrow morning. Shall I speak the lights out?"

They settled into the bed. Lucile was always a bit uncomfortable sleeping with a new partner, but the bed was big, and she did like Godfrey. He'd let go a few of the secrets of the virus, including calling up a genomic profile from Marsnet. It was proprietary, but he had a password and went into NutriTopia Ares's file system. She'd copied it and tucked a duplicate into her own private files.

The wonderful thing was, she could just sit back and not do anything.

Mars itself would do the work.

Lucile was pleasantly dozing when she heard Bon Bon hacking up a hairball on the carpet. The coughing went on too long to be just a hairball. Bon Bon had been extra affectionate lately. Cats with kidney issues often sought the heat of human flesh. She switched on a light.

Bon Bon was convulsing on the floor by her bed. As she watched in horror, the little cat quivered one last time, then lay still.

Without answering Godfrey's sleepy "What's wrong?" she scooped the cat up, bundled on a trench coat, and ran to the emergency medical clinic.

The medico on duty worked on the little cat for over twenty minutes, but it was quite dead.

"The virus?" she said.

The medico washed off her handfilm and shook her head. "Poor little thing. We think it may be like heartwormsheart-worms: kill the parasite, kill the host."

Lucile was more than horrified. Her cat, her companion for eight Mars years, which had listened to her secrets and mirrored her slinking and her primping like a tiny mime, was cooling on a clinic table.

"Are you saying it could kill humans?" This was a nightmare!

At this point she realized that Godfrey had fumbled into his clothes and followed her to the clinic.

"No, no, no," said Godfrey. "The human test was completely successful! No ill effects whatever."

She turned on him with the fury of a global storm. "Then what killed my cat?"

He smiled unconvincingly. "It has to do with taurine enzymes. Uh, I don't think you'd understand—"

Oh, she was furious. "Try me!"

He buttoned one more button of his shirt. "The thing is, nobody completely understands it. We just know it works, because of the enzyme-blocking, you see."

The clinic medico said, "It's not really a parasite, like other protozoans. When a parasite evolves long enough with a species, it is no longer useful for it to kill the host. It eventually offers benefits to the host. When rats eat cat feces, the rats become infected. The rats' brains are changed. We think it might emulate a dopamine reuptake inhibitor. The rats begin to love cats. They are even attracted to the smell of cat urine."

"And this helps the cat." Lucile stroked the fur of her dead Bon Bon, who seemed asleep with half-open eyes. "Godfrey, how does the virus work? How do you know it won't kill everybody on this station? Even you!"

"The discovery was an accident. We were looking for a bacteriophage for a different disease."

She lowered her voice an octave and stalked closer to him. "How does the virus work?"

He backed away. "We—aren't sure."

She sank down on her heels on the floor of the clinic and buried her face in her hands, unconcerned that her coat gapped open and revealed her nudity underneath. She looked up at Godfrey and said, "You have killed my cat."

"I didn't—"

"Something was wrong. You must have known."

"All right!" he barked. "All right! We didn't test it on cats! We tested it on hamsters because hamsters are cheaper. Hamsters are like cats, aren't they? Small, furry, warm-blooded? And we tested it on Fred Remaura, and he did just fine."

Lucile could barely contain her fury. "This is really true? You tested this virus on hamsters and one man, and then you unleashed it on two thousand innocent people and—oh my God—we have over five thousand cats here."

"I'm sorry," he said meekly.

"You'll be sorrier," she said with icy calm, "if you're not off this station tonight. Within the hour."

"I can't—there's no rocketplane until—"

"So call Utopia for emergency evacuation. No, wait, I'll call Jean-Marie. We have a rocketplane we use for light delivery. It isn't pressurized, so you'll have to stay suited up the whole flight, but I won't have to look at your lying face tomorrow. Or ever."

Godfrey got all stiff. "You forget that NutriTopia Ares owns every molecule of this station, right down to—"

"And this is relevant how?"

"I am a stockholder in NutriTopia Ares! I have rights here."

"How delightful for you! But it won't do you much good if you're here beyond tomorrow morning."

Godfrey deflated. "Why not?"

"Because you'll be dead."

He backed off, shaking his head and staring at her. She locked eyes with him until he turned and fled.

She stroked the still body of Bon Bon and wept.

#

She told Jean-Marie, "The feral cats will save us. They inhabit the upper tunnels, where there is less protection from surface radiation. We have to do everything we can to ensure that some survive."

They fed and watered the feral cats. The cats died by the dozens, the hundreds. But Lucile, Benoît, and Jean-Marie fed them and took the bodies away.

#

Jean-Marie's cat Aristide Brewpub did die. And so did the cats Benoît kept, Coeurl and her kittens, Albedo One and Chimère, rare albinos.

Lucile herself went through a horrible patch, ill with headaches and jaundice. ("Been hitting the wine a bit much, Lucile?" Benoît had fleered, and then she had whacked him on the shoulder with her personal office.) She checked herself once more for toxoplasmosis, and the test said she was still positive, but a more expensive test, ordered from Utopia, said no, she was clear of the oocysts. She threw into the recycler silky heaps of expensive lingerie and stiletto-heeled boots with built-in gyro stabilizers to prevent a twisted ankle. She mourned the woman she had been.

How could she have enjoyed being the slave of that microscopic tyrant, the puppet of that parasite? How tragic to be human, to ride the waves of passion steered by the wayward blood. Who was the real Lucile, the manic flirt, in love with color, self-adornment, and complex flavors on the tongue, or the sad rational woman cured of her infection?

Benoît did indeed remember the multiplication tables again, and proved to be such a finicky organizer of her life and Jean-Marie's that she could barely tolerate the glare of clean desk surfaces.

She wanted a kitten. She wanted to be sexy. She didn't want sex, she just wanted to be crazy and attractive again.

She wanted to be a kitten.

#

It took an entire Mars year for the die-offs to cease.

But.

As hard as it was, Lucile and the others had only one weapon: time.

Time, and the extreme environment of Mars.

The very harsh environment that forced the people of Gari Babakin to live under meters of regolith proved to be their friend.

It was just as she had learned from the notes in the NutriTopia Ares files.

Toxoplasma gondii was a protozoan similar to Plasmodium, the parasite that, on Earth, causes malaria. The difficulty of wiping out malaria on Earth is that the protozoan keeps mutating, so a drug that works one year will lose its efficacy a few years later. The protozoan mutates, develops immunity. On Earth, Toxoplasma gondii never did this, maybe because there was never a concerted effort to wipe it out.

But more likely it was because on Earth, Toxoplasma gondii didn't mutate very fast.

Mars organisms, all of them, are bathed in constant cosmic radiation. The radiation speeds mutations, and most of these are harmful. But if you're a parasite, and you reproduce very fast—

So they had only one solution: to take very good care of the cats in the upper tunnels, where the mutations would occur fastest.

The best meat. Carefully formulated meals, with plenty of taurine. Clean water always available, from cat-sized drinking fountains.

"We must be very brave now," whispered Lucile. She squeezed the hands of Benoît and Jean-Marie.

#

At the end of a Mars year—such a long time!—Lucile roused herself to take Benoît and Jean-Marie up to the tunnels where they had been cosseting the feral cats.

The cats looked different this time. Many of them had been dull-coated and listless the previous times they had visited. Today, there were fewer cats—so many had crawled away to die, and would have to be found and cremated—but those remaining were sleek and lively, fleeing the humans, or turning on them, puffing up with hisses and growls.

Lucile cornered one and picked it up to examine. It struggled fiercely, but she gripped its back paws and soothed it with her free hand. Then she peered closely into its eyes. Its mucosa were pink and unblemished, its fear and fury palpable signs of health.

She clipped one of its claws too short and harvested a blood sample to take back to the lab.

It snarled and would have bitten her but for her quick reflexes. She let it go and it streaked away, leaving claw marks on her arms. But she smiled.

Benoît caught her hand up and licked away her blood.

"All we had to do was take care that some of them survived," she said.

#

The cats were hard to count, but the estimate was that thirty cats were still alive on Gari Babakin Station.

And the one Lucile had tested bore toxoplasmosis oocysts.

Which meant that they probably all did.

And those oocysts now contained Toxoplasma gondii that were immune to Godfrey's virus.

#

The surviving feral cats were reproducing. Godfrey Worcester hadn't dared come back to the station, but he had sent Dr. Hilda Wriothesley and Dr. Kermilda Wrothe, who wrung their hands and scolded, but since cats are easy to hide, they didn't have much wind in their sails, and besides, there was an outbreak of athlete's foot in Argyre Planitia City.

Nobody from NutriTopia Ares apologized, and Lucile nurtured a small cold emerald of hatred in her heart.

#

Benoît gave her a tiny kitten. It clung to his shirt until he detached each of its twenty-four claws and handed it to Lucile.

"Where did you get it?"

He raised his eyebrows.

"It has a name?"

"I offer you that honor."

"Éclair," she decided. Éclair sank its twenty-four tiny needles into the fabric of her jumpsuit and purred. Its body was very warm. Its tongue was very pink.

"The feral cat colony is back in force." Benoît tried not to smirk.

"I thought everybody would take all the remaining cats for pets, after most of them died."

He shrugged. "Not all cats agree to be pets, just as not all Martians agree to play kiss-ass with the corporate jackboots. Some old toms fought like tigers. They don't trust humans, after what happened."

"And they all have toxoplasmosis? The virus has run its course?"

"Apparently. And people are eating raw meat again. They're raising hamsters to make steak tartare, imagine that."

She smiled slowly. "What a scandal."

#

The medico at the clinic which had failed to revive Bon Bon had theories of her own. On Earth, toxoplasmosis benefited cats because cats were the top predator in their environment. Humans didn't count in that environment, because they didn't prey on either cats or rats. But on Mars—well, certain humans could be top predators. At least, the mutated toxoplasmosis seemed to foster that situation.

But their prey was other humans, those of a different genetic background, in a suave and civilized way. Because NutriTopia Ares failed to understand that the virus hadn't completely wiped out toxoplasmosis, it spread wherever food was shipped from Gari Babakin.

Those with these secondary infections, with the other genomic background, behaved like prey animals. Prey animals that don't die, but rather buy. They were infatuated with all the products of Gari Babakin culture.

#

"We are the Paris of Mars," Lucile said. She twirled, enjoying the swirl of her new red frock. Benoît and she had designed it, and now she was modeling it for a test audience: him and Jean-Marie. Soon she would offer it, as she had other creations, to the wealthy of Mars. Benoît had a flair for design, it turned out, though she didn't trust him to keep the Chez Raoul company books. She hired a woman for that.

She did, however, trust Benoît to father a child. The two designers did not breathe entirely easily until the little boy had reached his second birthsol and showed no damage from toxoplasmosis.

Étienne LeBouef had opened a small restaurant that required reservations a Mars year in advance. A mysterious vigneron now bottled a wine so exquisite that Terran billionaires paid huge sums to have it shipped to them on Earth.

Dr. Hilda Wriothesley and Dr. Kermilda Wrothe won Mars Global Storm Awards for their work in protozoan dopamine metabolism. Lucile watched the ceremony via netlink.

"Oh, look, Tigercat," she said to Benoît, "they're wearing knockoffs of our gowns."

Benoît, busy composing a poison pen letter to the Prime Minister of Key West, wasn't watching. "How do you know they're knockoffs?"

"Darling, we'd know if orders had been placed. And neither of them can afford originals. But more to the point, look at how they drape. Droplet manufacturing can't even approximate the real thing, eh?"

#

Dr. Godfrey Worcester, sadly, found himself unable to do serious science after his collaboration with Drs. Wrothe and Wriothesley. He disappeared. Rumor had it he was deported to Earth after his arrest for stalking Lucile Raoul.

He said he loved her.