Leah Cutter tells page-turning, wildly creative stories that always leave you guessing in the middle, but completely satisfied by the end.

She writes mystery of all sorts. Her Water Witch cozy paranormal mysteries have been well received by readers, who just want to curl up and have tea with the main character. Her Halley Brown series, revolving around a private investigator who used to be with the Seattle Police Department, leave you guessing at every turn. And her speculative mysteries, such as the Alvin Goodfellow Case Files—a 1930s PI set on the moon—have garnered great reviews.

She's been published in magazines such as Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine and in anthologies like Fiction River: Spies. On top of that, Leah is the editor of the quarterly mystery magazine: Mystery, Crime, and Mayhem.

Read more books by Leah Cutter at www.KnottedRoadPress.com.

Follow her blog at www.LeahCutter.com.

Read more mysteries at www.MCM-Magazine.com

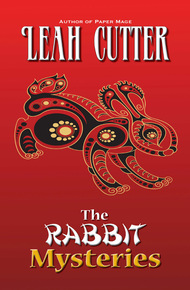

Rabbit works as a law clerk, spending his days with contracts and land leases. At night, however, he spends times with his friends and solving mysteries.

Collected together for the first time are all the Rabbit stories, which take place during the Tang dynasty, in China.

Included in this collection are:

The Curious Case of Rabbit and the Temple Goddess

Rabbit and the Mysteriously Missing Daughter

The Strange Mystery of Rabbit and the Stolen Song

Rabbit, The Dastardly Thief, and the Disappearing Dragon

Plus, Old Friends, a story about Wei Fu, Rabbit's master in the later tales.

The Curious Case Of Rabbit and the Temple Goddess: Scene 1

I was late. Again.

And though I knew Master Wei was waiting for me, as impatient as ever, and the gate tower had just sounded the mid-morning hour of the Snake, I still ducked out of the bright spring sunshine and into the temple at the corner of the market.

Familiar peace descended on me in the darkened space. The sounds of the market just beyond the walls faded.

Nine mystical candles stood lit on the rustic wooden altar against the far wall. They were carved with ancient symbols, and circled the tiny silver statue of our beautiful local goddess, Bái Hua Bàn.

I was glad to see that someone had lit them: since the priest had died the month before (and Xin Chao still claimed under mysterious circumstances, not just bad luck) the candles weren't always lit, the rough brick floor not swept, and dogs allowed to foul the temple. The search for the deed to the land the temple sat on hadn't shown up either, more bad luck.

However, my goddess stood, poised as ever, a mysterious smile lurking at the corners of her mouth. Her wide eyes and broad brow showed great intelligence. She stood in flowing robes, offering a simple blossom with both hands to her devotees, a symbol of her purity and great fecundity.

Bái Hua Bàn brought rains to the surrounding fields, children to brighten our days, and wisdom to the elders who guided us. We would be nothing without her, just a speck on the Emperor's maps, a footnote by the census takers, about how this town had once been at this place, and now was no more.

I took a moment to breathe in the stillness, to fortify myself with the goddess' calm before returning to my hectic day. Some called the temple insignificant. It was only large enough for two dozen standing followers at best. I called it cozy, and comfortable, and in many ways, mine. Though I wasn't a priest, I still attended her, every day, more faithful than a husband.

After my eyes adjusted, I slowly made my way forward over the rough floor—I'd stubbed more than one toe, and broken more than one sandal strap, when I'd used haste. No pews impeded my way: they'd all been shoved to the sides.

I was aware that it was ironic, that someone named Tù, or Rabbit, would be so clumsy, and always move slowly. And it was just Rabbit—not Young Rabbit or Old Rabbit, not Fat, Thin, or Spry Rabbit. Not even Number Three or Number Ten Rabbit. Just plain Rabbit, a fitting enough name for an unlucky fourth son of a now-widowed mother, the only one still unmarried and living at home.

When I was close enough to smell the lilies on the edge of the altar, I realized someone else shared my haven. He was prostrate on the floor, covered in a dark cloak, a mere shadow.

He hadn't positioned himself in the middle, the Emperor's place, but to the stronger, right-hand side.

I moved to the left side to give him some privacy, though I was curious. I didn't recognize him, and I knew all the goddess' followers. Maybe he was some foreigner and the goddess had spoken to him, calling to him from far away.

I bowed to the corners of the world, starting with the west, where the sacred Emperor and his golden court reigned, then to the north, where the horse barbarians waged endless war, to the east where tales of strange beasts and the ocean lay, finally, to the south where there were yet more barbarians, but at least they were our own.

Then I bowed to the most important point, the center, where the town of Da Shan rose up and spread around me, the heart of my world.

Only then did I kneel and prostrate myself, giving all I had to my goddess.

I've had scholars argue with me at Tang's Tea Shop, claiming that she's just a local goddess, here, at the southern end of Da Shan. That I shouldn't pay her so much attention, she couldn't be that important.

I told them I didn't care what other gods or goddesses existed elsewhere, even at the north end of the town. She was important to me.

Bái Hua Bàn was who I poured my heart out to, who I entrusted with my secrets. I told her of my upcoming day, the trials of being merely a clerk, not even an apprentice, of my cramped, ink-stained fingers, my caged soul that longed for poetry but was enslaved to writing contracts.

She never replied. I didn't expect her to. Not really. I was just a lowly clerk.

Still. I visited her every day, and since the priest had died, more often than that.

I kept my thanks and ramblings short that morning, asking her for blessings for myself, my mother, my master, my town, and my emperor.

When I raised my head, I wondered briefly if a storm had suddenly gathered. The temple was no longer as brightly lit.

Had some of the candles blown out?

It took me another long heartbeat to realize that the nine candles burned around an empty spot.

The statue of the goddess was gone.

As was the shadow man.

Trembling, I stood, unsure what to do.

Fat Ang, the local magistrate, wouldn't believe any tales of a shadow man. He would send his bullies to pick up whoever he thought needed a lesson.

Or he might accuse me of such a crime. I was always here.

No one would search for the real thief.

I moved closer.

A single petal from a white lotus flower marked the spot where my perfect Bái Hua Bàn had stood.

Before I could gather up this precious artifact, the edges of it started to brown. As I watched, lines of age shot through the creamy flesh, withering the petal, as if a hidden winter hand had scraped its poisonous fingernail along it. It finally shriveled up completely and disappeared.

The message was clear.

I must find the statue, and return it, or all the bad luck Bái Hua Bàn constantly held back would descend. It would be worse than any plague or famine: My town would be no more.