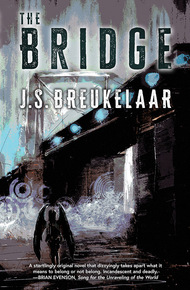

J.S. Breukelaar is the author of Collision: Stories, a 2019 Shirley Jackson Award finalist, and winner of the 2019 Aurealis and Ditmar Awards. Previous novels include Aletheia and American Monster. Her short fiction has appeared in the Dark Magazine, Tiny Nightmares, Black Static, Gamut, Unnerving, Lightspeed, Lamplight, Juked, in Year's Best Horror and Fantasy 2019 and elsewhere. She currently lives in Sydney, Australia, where she teaches writing and literature, and is at work on a new collection of short stories

Meera and her twin sister Kai are Mades—part human and part not—bred in the Blood Temple cult, which only the teenage Meera will survive. Racked with grief and guilt, she lives in hiding with her mysterious rescuer, Narn—part witch and part not—who has lost a sister too, a connection that follows them to Meera's enrollment years later in a college Redress Program. There she is recruited by Regulars for a starring role in a notorious reading series and is soon the darling of the lit set, finally whole, finally free of the idea that she should have died so Kai could have lived. Maybe Meera can be re-made after all, her life redressed. But the Regulars are not all they seem and there is a price to pay for belonging to something that you don't understand. Time is closing in on all Meera holds dear—she stands afraid, not just for but of herself, on the bridge between worlds—fearful of what waits on the other side and of the cost of knowing what she truly is.

This is a superb novel by J.S. Breukelaar that straddles the realm of supernatural and science fiction. The primary character, Meera, is a Made, part human, part not, created by the crazed leader of the Blood Cult. Meera made it out of the cult, thanks to a witch named Narn, but her sister, Kai, was not as lucky. But Kai may not realize that as she continues to haunt her sister Meera, and their story is a page-turning, poignant one. – Tricia Reeks

"Immerses the reader in a complex world with a complicated protagonist … Breukelaar's dark novel is spellbinding."

– Paula Guran, Locus Magazine"Gothic and feminist, J. S. Breukelaar's novel The Bridge is moving in addressing science, sisterhood, and storytelling."

– Aimee Jodoin, Foreword Reviews"A startlingly original novel that dizzyingly keeps erasing and redrawing the distinction between magic and science fiction as it takes apart what it means to belong or not belong. A story about reparations, necromancy, and college cliques, and about the way in which the world, in being made and remade, remains both incandescent and deadly."

– Brian Evenson, Shirley Jackson Award-winning author of Song for the Unraveling of the World"The Bridge has one foot in dystopian darkness and one foot deep in a mythology that feels both new and subconsciously familiar. All at once beautiful and terrifying, this is horror that hits close to the heart and close to home."

– Sarah Read, Bram Stoker Award-winning author of The Bone Weaver’s OrchardI was raised by three sisters—one a witch, one an assassin and the third just batshit crazy. By the time I left our home deep in the Starveling Hills, I'd met the middle one, Tiff, once, but I never told the others. She'd run off or something, and they didn't talk about her much, and maybe it was for that reason that she was my favorite—her ghostly absence having as big an impact on my growing-up as the others' larger-than-life presence. When I finally came to live in the Hills, carrying my own dead twin in my arms, Tiff was already gone, leaving behind nothing but bad blood and a trunk filled with old clothes from across the ages. Among them were a pair of Roman sandals that fell apart in my hands, some rusted crinolines, a moldy cat-o'-nine-tails, some concert T-shirts and even a notebook from her days at the Blood Temple with the Father—bound in the skin of one of her victims, for all I knew. The pages were scribbled in with illegible symbols which set something humming inside me, convinced me from day one that "Aunty" Tiff wanted me, and only me, to find her.

I was good at finding lost things, Kai always said, and they were good at finding me.

In time Narn, the eldest sister, sent me away to Wellsburg college, ten thousand miles away and on the other side of the planet. To the ends of the earth, may as well have been.

I had arrived at the campus just before the start of the semester and was soon sick with one of my frequent chest infections. I lay awake in the Tower Village dorm room, feverish and snotty, too ill to go to the first week of classes, forgetting why I was here. The damp pillowcase chafed my cheek. The weary thwack of a campus security pod overhead tangled in the jerky drum of my heart, and I tried to push thoughts of the Father's birds away, couldn't help wondering how far I had really come from all that—Narn and her crazy sisters and my sister Kai, buried under a bloodwood tree, high in the Starveling Hills. I tried not to think. I tried not to ask myself if it would ever be far enough.

My pajamas, blue plaid with pink elephants, were damp with sweat. They insistently nudged between my legs. I shifted on the mattress, trying not to think of the downy young shearers who drank at the pub in the nearest town to our hut—a twenty-kilometer drive in Narn's truck, but worth every pothole. I was nineteen and Kai would be too—my better half as Narn called her, not joking. Narn never joked. Maybe that's why Kai had been her favorite from the beginning—law of opposites or something. My sister always joked, even when she lay in the Blood Temple infirmary covered with sores and the Father already sharpening his scalpels for the unmaking.

Even then.

The door opened with a click. I squeezed my eyes shut, hoping my roommates, Lara and Trudy, would leave me alone. Their laughter subsided when they saw me still in bed, but they continued their conversation in whispers—something about an urban myth of a ghost of a fur hunter from the 1800s who crawled out from under the bridge after being pushed to his death by a witch.

"Yes, but don't most old colleges in the Slant come with some kind of scary story?" Trudy was saying. "In orientation they told us . . ."

I couldn't resist. Partly because in the mostly bedridden week that I'd been at Tower Village, I'd barely spoken or been spoken to, but also because long before I'd even gotten here, Narn had versed me in the history of witches' rights. "He jumped!" I croaked. "Probably. They had to blame somebody. Why not witches?"

"Know-it-all," Lara said beneath her breath.

No, Kai was the know-it-all. Always had been. My cheeks burned with fever, but there was no stopping me now. Kai always said how just a sniff of threat was enough to make me see red.

"Witches got the blame for the fur trade drying up in Upper Slant," I continued. "People said they poisoned the game—even after the Apology it wasn't safe for them here."

The air in the dorm room was stale. My nose was blocked with congestion so I drew it in as best I could through my mouth, watching Trudy dart through the shadows like a bottom feeder through lakeweed, for a moment the meds and the fever telling me that it was Kai. That my twin was not dead after all and I was home in the Starvelings and the Father had not found us as she always said he would. But then Lara flicked on the light and I blinked into the reality of what I'd lost.

Lara moved to check her roots in the mirror for telltale regrowth. Like all Mades, her hair was course and dull, but she'd applied conditioning treatments and lightened it to a chestnut brown, had it cut into a curly bob that suited her. "It stinks in here," she said.

"Anyway, what do you care about myths?" I propped myself up on a wobbly elbow. "We have enough problems with reality."

Lara and Trudy were made on the Blood Temple's mainland property but the Father's synthetic reproductive protocol was the same there as it was in Rogues Bay, where I was from. Their teeth looked ultraviolet in the blue-stippled light from the bridge outside our window. Their forms were limned in a milky afterglow which seemed to slow their movements one minute, speed them up the next, silvery jetsam shredding in their wake. Or maybe it was just the meds.

"The counselor in pain clinic said we shouldn't fixate on the past, Meera," Trudy shivered mechanically, "if we want to belong to the future."

I wanted nothing less.

"Well, we can't fixate on the past," I said. "It's not how we're, um, made."

It was something my sister would do—hiding good intentions behind a dark pun, an offhand joke—but I sucked at reading the room, something Kai never let me forget. Instead of admiring my cleverness, Trudy's eyes brimmed and she reddened in the shame of our shared congenital amnesia.

"Myth or not," Lara turned defensively from the mirror, fastening a chain around her wrist from which dangled a rose-gold feather, "they've put a curfew out now that semester's started. The bridge is off-limits after ten."

"Why?" I asked.

"To keep us where we belong," Trudy sniffled. "Especially after dark."

They moved about, preparing for the night. Later they would come home smelling of beer, faces bleached in the light of their program-issued phones, and fall immediately asleep dreaming, I imagined, of a new tomorrow.

What I really felt like was a drink, but before I could ask them to wait while I dressed, Lara reminded me that today, Thursday, was the last day to sign up for our second-choice electives. And that we needed these for credit point requirements to complete our transfer program in the specified time of eighteen months.

"The sooner we complete the program," she said, "the sooner we can get out of here."

"I almost forgot."

"You did forget," Lara eyed my pile of snotty tissues. "And you need to get up now, Meera, or you never will."

I hacked phlegm into another tissue. My nostrils were chaffed and there was blood in my snot. Unlike most of the Redress Award recipients, including my roommates, who had followed the award recommendations and arrived during the summer, my body had not had time to build up the required immunities. Nor had my brain gone through the regulation mnemonic and behavioral reconditioning. The dormitory pulsed black and blue in the light from the illuminated bridge. It wasn't much different from how my eyes would open into the half-light of the little room I shared with my dead sister in the Starvelings, before closing once more on the shifting optics of a digital dream.

Unfamiliar constellations pricked the alien September sky. I looked through the window high up in my Tower and thought how I wanted to be here—didn't I? Yet a part of my consciousness did not. Some part of me—my mind—remained in South Rim where, beneath Crux and the Jewel Box, blossoms would be blowing across my twin sister's grave beside the bloodwoods. Where Mag would be cleaning their gun and Narn would be peeling potatoes while she stirred a cauldron of beans on the stove—she was a terrible cook of everything but sweets and libations, and even from here, I could taste the burnt scum from the bottom of the pot, smell the lemon myrtle in her velvety pudding and the stinking hellebore in her soup.

But my heart could not.

The walls spasmed in another flash of electric blue. I closed one eye. Through the window of the high dorm, saw a shadow haltingly separate from a row of unintegrated shapes on the bridge and unfurl what looked like fleshy wings before drawing them once again into itself and settling hunched in the cold blue light. When I opened my eye, it was gone.

The medication I'd stolen from the bathroom made my head fuzzy. In my footlocker I kept some of Narn's A. sarmentosa tea for pain, but I couldn't recall the sorcery required to activate it. The words were written down somewhere—Kai had seen to that—but ink in the hands of the dead tends to ravage the paper it's written on.

The Regulars called us survivors—although none of us saw ourselves that way: we called ourselves Mades. The Father made us by inserting a soluble microscopic implant laced with his Forever Code into a human female zygote in vitro, birthed from a surrogate we would never know. I was raised along with thousands of others in the Blood Temple, which flourished in remote Southern Rim camps for just shy of three decades, although the first years were much less productive than was hoped. According to our Father, Mades, by virtue of our . . . virtue, would be the bridge to lead man back into the Paradise from which he'd been so unjustly expelled. It made perfect sense at the time. We understood the Father. He made us feel his pain as if it was our own.

It was our own.

My roommates went out, leaving me alone with nothing except a reminder of my own amputated singularity. Lara was right. I needed to get out of here and the sooner the better. I crawled from the bed to Trudy's bunk and helped myself to two pills from one of her many bright jars purchased from the pharmacy. If they knew I was stealing their meds, they didn't say. They brought me things sometimes—cough drops and once, some soup. My throat was on fire, and my nose so congested that I'd dreamed last night of drowning, of hanging, of a hand across my face.

I heard a snuffling under the bed, that cheap-carpet drag, and slowly lifted the sheet, my breath coming quick. I was maybe expecting the spotlit eyes of a lost flying fox, like once back in the Blood Temple—dragging itself by its broken wings, it had looked more insect than mammal—but there was nothing. Each night since arriving in Upper Slant, I'd had the same dream, or different versions of it. Kai and me playing on the lichen-striped outcrop even though I am already too old for games and Kai is already dead. She taunts me through lips black with rot, teeth hanging by ropy gums in her still beautiful face. In my dream the shadow when it first appears is both distant and too close, a shadow without a shadow, erect as a monument, the ravens circling overhead with their iridescent wings and their sad-baby cries, Kai rank and rotting beneath a sky too high and never high enough. "He'll always find us," she gurgles. "We'll never be free."

In my dreams it was Kai the guilty survivor instead of me.