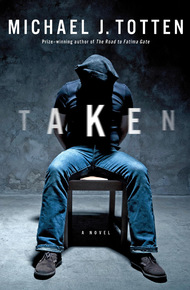

Michael J. Totten is an award-winning journalist and prize-winning author whose very first book, The Road to Fatima Gate, won the Washington Institute Book Prize. His novel, Resurrection, has been optioned for film.

He has taken road trips to war zones, sneaked into police states under false pretenses, dodged incoming rocket and mortar fire, stayed in some of the worst hotels ever built anywhere, slipped past the hostile side of a front line, been accused of being a spy, received death threats from terrorists, and been mugged by the police in Egypt. When he's not doing or writing about these things, he writes novels.

His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic among numerous other publications, and he's a contributing editor at World Affairs and City Journal. He has reported widely from the Middle East, the former Soviet Union, Latin America, and the Balkans. A former resident of Beirut, he lives in Oregon with his wife and two cats.

A writer is ripped from his home and hauled bound and gagged to a remote house in the wilderness.

Four ruthless captors with overseas ties and a plan here at home—the frighteningly rational leader of a homegrown Al Qaeda terrorist cell; a torturer who learned his trade in the dungeons of Egypt; and two henchmen, one a grinning sadist who can hardly wait to start cutting.

Taken on a harrowing journey across three states into his very worst nightmare, he faces a terrible choice. Prove himself and join them. Or die.

Michael J. Totten has walked through some of our nastiest wars in the most dangerous way possible, as an award-winning journalist. Read his bio and then try to imagine the pleasant, easy-going guy I've sat beside many times… I'll just say that it doesn't make sense until you meet him. Michael has given a lot of thought to what it means when the war comes home and in Taken he offers a chilling view. And how does he do it? The same way he does it in real life, he puts himself right in center of the story. – M.L. Buchman

"Absolutely terrifying."

–Benjamin Kerstein, author of The Forsaken"The author drives the plot with a determined hand. He shows a talent for describing scenes of action and intensity which has already been apparent from his reporting on Iraq and Lebanon. But the book is also a novel of ideas, and a character study."

–Jonathan Spyer, The Jerusalem Post"In the spirit of Hunter S. Thompson, Mike Totten gives us a fascinating fictionalized hypothetical using himself as a character, a nightmare scenario for any writer who dares to focus on the sensitive topic of the Middle East. It boils down to a couple of disturbing questions: What if the terrorists come for me? What if they take me from my home? How far would I go to get free?

In this taut, riveting book, he grapples with those very questions, bringing to bear all his years of experience working as a prize-winning journalist focused on some of the world's most troubled areas. Read this book. If you're like me, you'll find yourself double-checking your locks at night long after you finish it."

They took me from my house in the night. Rough hands slapped duct tape over my mouth and I sat up in bed, head swirling with gray shapes and vertigo, wondering if I was dreaming, but before I could yell, before I could reach up and rip off the tape, two hundred pounds of muscle and purpose shoved me back down onto the bed.

My wife was out of town teaching a class in Seattle, and I hadn't bothered to turn on the alarm system or the motion detector downstairs. I didn't hear the back door open, nor did our cats alert me that dangerous strangers had entered our home.

I kicked with both legs but only flailed against my own sheets and blankets. A mass of hands gripped me, flipped me onto my stomach, and jammed my face into the pillow. I could hardly breathe as steel cuffs slammed around my wrists, the metal digging hard against bone.

For a moment I thought I was being arrested, that police officers had raided the wrong house, that I'd be released soon enough—and with an apology—after they took me down to the station and realized they had the wrong guy.

The moment was fleeting. I will never forget the sound of the voice I heard next: calm, professional, and chillingly void of emotion.

"Get the blindfold on him."

The man who uttered those words, I knew, would gut me as remorselessly as he would crush a beetle under his boot.

Get the blindfold on him.

Quick and certain, with just the slightest touch of impatience.

Get the blindfold on him.

Unaccented American English from a man who couldn't be over thirty.

Get the blindfold on him.

They tied what felt like a pillowcase over my eyes. It covered everything from my nose to my forehead. No chance I could sneak a peek over the top or under the bottom. Two hands gripped each of my thrashing limbs and hauled me off the bed and down the stairs. I heard what sounded like work boots on hardwood, but their hands on my skin felt soft, not like those of laborers. I managed to fling an arm free and knock a picture frame off the wall, but they restrained me again and dragged me out the back and into the driveway at the side of the house.

A van door slid open. As I struggled to yell through the duct tape, they dumped me onto the van's grooved metal floor. Two men climbed in with me, each holding one of my arms. The other two hopped in front. When I heard the ignition turn over, I arched my back and kicked one of the bastards. Either a fist or an elbow—I couldn't be sure—slammed into my mouth, mashing lips against teeth.

I tasted blood and iron and smelled body odor—theirs—as we hurtled down surface streets, the van's engine gunning like a getaway car, and merged onto the interstate.

*

My name is Michael Totten, and I work as a foreign correspondent in the Middle East. For ten years I feared something like this might happen. It's a hazard of my profession.

Khaled Sheikh Mohamed kidnapped my colleague Daniel Pearl in Pakistan and beheaded him on camera with a kitchen knife. Murderous drug cartels south of the border have turned Mexico into one of the most dangerous countries on earth to work as a reporter. During the Lebanese civil war in the 1980s, Hezbollah kidnapped journalists and chained them to radiators. I'm always taking a risk when I leave the comforts of home to report from the unfortunate parts of the world. I was especially concerned about being snatched off the street during my seven trips to Iraq, but I had no idea I'd ever be yanked out of bed in my hometown in Oregon.

Nobody said anything as we drove. Whoever these guys were, they weren't talking. I tried to curse them but could only groan into the tape over my mouth. All I could hear was the thrum of the engine and the vibration of the wheels at interstate speed. If I'd been congested and couldn't breathe through my nose, I would have suffocated.

The van's floor dug into my back. My wrists ached from the handcuffs, and a muscle in my right shoulder cramped up. I noticed the smell of sweat in the blindfold that covered most of my face and realized it was my own.

After hours had passed, we finally stopped. It felt like four hours, but it must have only been three. Surely my sense of time was distorted. At least I no longer cringed and expected to be punched or elbowed again.

The man in the passenger seat got out and unscrewed the van's gas cap. I listened carefully. Was anyone else out there? Would a gas-station attendant see or hear me if I kicked and thrashed and made a big enough scene? Did the van even have windows? I imagined it probably didn't.

But there was no attendant. Nobody asked how much gas or what kind we wanted. I heard the man from the passenger seat swipe a credit card and insert the nozzle into the tank.

We were no longer in Oregon then. Self-service at gas stations is illegal in Oregon. You have to wait for an attendant to fill the tank for you. So at some point in the night, we had crossed into Washington. It had to be Washington. My house in Portland is just a fifteen-minute drive to the state line, but California and Idaho are six hours away. Nevada is eight hours away. Canada is also six hours away, and there was no chance I'd missed an international border crossing.

We left the station and after another hour or so, the van slowed and turned. The tires crunched onto gravel. I braced myself. This was it. Wherever we were going, we had arrived.

The man in the passenger seat climbed out and opened the sliding side door. The scent of pine overwhelmed me at once. We were in a forest, or very near one, and we were on the dry eastern side of the Cascade Mountains rather than the wet western side, where the forests are fir. I figured we must be somewhere in the vicinity of Yakima or possibly Ellensburg, a college town in the middle of the state.

The duct tape over my mouth was ripped away stingingly.

"Will you walk?" It was that voice again. The one that said "Get the blindfold on him."

"I'll walk," I said, "if you take off the blindfold."

"Get him in the house," he said, and I felt myself hoisted by my shoulders, the tops of my bare toes trailing in gravel. "Go ahead and scream if you want. No one will hear you out here."

A supernova of hatred exploded inside me. If they looked like they were going to kill me, I'd fight them. And if they kept me in cuffs and held down my legs, I'd bite the bastards' fingers off with my teeth.

*

They took me inside, dragged me into a basement, and sat my ass down in a straight-backed wooden chair no softer than the van floor. They uncuffed one of my wrists and recuffed it to a table leg. I heard heavy booted footsteps heading up wooden stairs toward the main part of the house.

I sat hunched over in absolute silence with my shoulders nearly up to my ears. I figured they'd left me alone, but when I reached up with my one free hand to take off my blindfold, I saw sitting before me a man of about thirty with blue eyes, dark curls, and light brown skin. With a face like that, he could have been from a number of places around the world. Italy, Chile, and Armenia come to mind now, but I knew at the time he was almost certainly an Arab. He could have been from Pakistan or Iran, but I doubted it.

Behind him stood a hairy bear of a man with black eyes, a long black beard, and short-cropped hair. He was the one who had punched me. I could tell. He had an I like to kick the shit out of people look on his face.

"Michael," the blue-eyed man said. "Believe me, it is a pleasure to finally meet you."

I stared at him and tried as hard as I could to show no expression. No anger. No fear. Then I sucked my teeth hard enough to make my split lip bleed again, leaned to the side, and spit blood onto the floor.

"Sorry about that," the man said. "But you were flailing about and kicked Mahmoud here in the ribs."

The larger man stood there with his arms folded and drummed his fingers on his biceps at the sound of his name. I turned and wiped the blood off my lips and onto my shoulder.

"My name is Ahmed," the blue-eyed man said.

"Ahmed what?" I said. "What's your last name?" I've spent enough time in the Arab world that I can sometimes tell which country people are from by their last names.

"Just Ahmed for now," he said. "We have a job for you."

"I'm not working for you," I said. "Shoot me if you want, but I'm not going to help you."

I honestly didn't know if I meant that or not. They expected me to resist and they weren't beating me up, so what was I supposed to say? Sure, okay, I'll do what you want?

"I can understand your reluctance," Ahmed said, "but you will do what we say."

I looked at him and said nothing.

"We aren't necessarily going to kill you or even hurt you," he said. "As long as you do what we say. If you cooperate, we'll see what happens."

He could tell by the look on my face that I didn't buy it.

He sighed. "If I told you we'd let you go if you cooperate, would you believe me?"

"No," I said.

"Okay then," he said. "I didn't think so. So I won't insult your intelligence."

"What do you want with me, Ahmed?" I started grinding my teeth. I resisted clenching my hands into fists, but I couldn't help grinding my teeth.

"I appreciate that you're pronouncing my name correctly," he said. The h in his name is aspirated. It's pronounced like the h in house.

"Of course I know how to say Ahmed," I said. "I've been working in and writing about the Arab world for ten years."

"Yes," he said and smiled. "I know. That's why we picked you."

"Why me?" I said.

"I just told you," he said.

"No, I mean why me of all the American journalists who cover the Middle East? Why not kidnap ¬¬¬Peter Bergen or Tom Friedman? They're both more famous than I am."

"Because," he said and stood up. "You have a widely read blog. And you're going to give us the password."

I had a blog at the Web site of The Global Weekly, where I published a weekly column, daily takes on the news of the world, and occasional long dispatches from war zones and trouble spots. I could write whatever I wanted. Unlike traditional journalism, my work was published instantly and unedited with the click of a mouse. If Ahmed had my password, he could hijack my column and publish whatever he wanted himself.

Mahmoud unfolded a four-inch Leatherman knife and flicked his thumb across the blade sideways. It took everything I had, but I resisted.

"I'm not giving you the password," I said and swallowed hard. My hands felt clammy, and it was all I could do to keep myself from shaking.

"Cut off his eyelids," Ahmed said.

Mahmoud grunted and stepped forward, the cords standing out in his neck. I spasmed as though I had just been zapped with a cattle prod.

"Okayokayokay," I said and gave up the password.

"That wasn't so difficult, was it?" Ahmed said. "You will do what we say. And it will be easier on everyone here if you immediately do what we say. Don't ever say no to me again."

I tried hard not to breathe too heavily, but it was difficult.

"You kidnapped me just to get my blog's password?" I said.

"That's just for backup," he said. "For insurance, you might say."

"Against what?" I said.

"Insubordination," he said. "If you don't do what we say, Mahmoud will cut off your eyelids, take a nice pretty picture, and upload the photograph to your blog. Even your wife and mother will get a good hard look at what's happening to you."