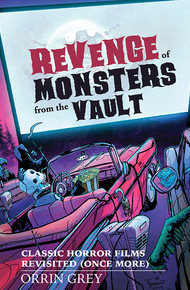

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, tabletop game designer, amateur film scholar, and monster expert whose stories of monsters, ghosts, and sometimes the ghosts of monsters have appeared in dozens of anthologies, including Ellen Datlow's Best Horror of the Year. He's the author of several spooky books, most recently How to See Ghosts & Other Figments.

The monsters are back!

Dim the lights, grab some more popcorn, and get ready for another feature presentation as author, skeleton, and monster expert Orrin Grey takes you on another journey of vintage horror cinema.

Welcome back to the Vault of Secrets. Author, skeleton, and monster expert Orrin Grey has disinterred another batch of classic (or not-so-classic) vintage horror films for your delectation, spanning the decades from the silents to the Seventies. There'll be devil bats, ape fiends, space invaders, black cats, old dark houses, invisible dinosaurs, cat people, giant rabbits, monster skeletons, and a whole lot more! Beginning with a 1926 precursor to Frankenstein made by "the world's greatest director" and ending with Toho's infamous "Bloodthirsty Trilogy" of Dracula movies, Revenge of Monsters from the Vault is a reminder that every good monster deserves a sequel or three. So dim the lights, grab some more popcorn, and get ready for another feature presentation…

"It's a monster mania double bill! Take another trip into the vaults of classic monster movies with your guide, Orrin Grey." – Lavie Tidhar

"Orrin Grey provides a bite-sized introduction to vintage horror films. It's the perfect resources for those getting started in their classic film journey."

– bestselling author Silvia Moreno-Garcia"Orrin Grey's Monsters from the Vault is a delight. Grey takes the reader on a film-by-film journey trough some of the lesser-known horror films of the middle decades of the twentieth century, offering incisive and witty analysis of them along the way. Possessed of an apparently encyclopedic knowledge of these films, Grey points out connections among their directors, writers, actors, and production crews. The result is a book that can be enjoyed both for its discussions of individual films and for its overview of horror film during this period. Put this one on the shelf next to Danse Macabre and The Outer Limits Companion–even better, keep it on your desk, so it's close at hand."

– John Langan, author of The Fisherman.Introduction

Welcome back to the Vault of Secrets. For those who don't know, that was the name of the column on vintage horror cinema that I wrote for Innsmouth Free Press from 2011 until 2016, when the columns were all collected into the book that came before this one, Monsters from the Vault.

By that time, the column was coming out monthly, but I wasn't writing them a month at a time. Instead, I had written ahead by almost an entire year. When Innsmouth shut their online doors not long after the release of Monsters from the Vault, those additional columns suddenly had nowhere to go.

For a while, I considered just putting them up on my website, or offering them as exclusives on my now-defunct Patreon page, but ultimately, none of that felt right. So, I asked Silvia Moreno-Garcia if she would be interested in publishing a follow-up. After all, no good monster movie should be without at least one sequel, right?

Of course, I didn't have nearly enough spare columns to fill out a whole book, which meant that I would have to watch a whole bunch more movies from the 1930s, 40s, 50s, and 60s to finish it up. Quelle horreur!

This book is intended as a companion piece to Monsters from the Vault. If you don't have a copy, I recommend that you pick one up. I hope that the two go well together. If nothing else, they should look nice next to each other on your shelf or coffee table, or next to your Blu-ray player. There are also a lot of differences, though.

The columns collected in that first book were written over the course of five years. All of them were published online at Innsmouth Free Press, either as part of my Vault of Secrets column or, in a couple of rare instances, as part of an earlier column I had written about international horror films. A few of the essays in this book have been published online here and there—at Unwinnable, on my own blog, as guest posts for various other places—but the vast majority of the essays in this book are not available anywhere else, and never have been.

Most of these pieces were also written much closer together. While a few of these had already been penned when Monsters from the Vault was released in 2016, and a few more were written in the years in between then and now, about half of these essays were written toward the end of 2018 and during the first few weeks of 2019. I hope this means that the writing is, perhaps, a bit more consistent, and I know that it allowed me to draw parallels between movies in ways that viewing them months or even years apart precluded.

The essays in this volume are also considerably longer, on average, than those collected in Monsters from the Vault. That reflects, I hope, a change in the overall style of my film writing, even while the focus of these essays is the same as it was when I started way back in 2011—I'm not really here to tell you whether these movies are good or not, though sometimes I will, but rather to give the films context, draw parallels, describe the experience of watching them for the first time.

If you haven't seen some of these films, I hope I'll convince you to seek them out and form your own opinions. If you have, I hope that you find something new to enjoy about them, that I shine a light into some previously dark corner, filled with cobwebs and rubber bats.

Because the essays themselves are (sometimes considerably) longer, I cover fewer films in this volume than I did in the last one, but hopefully I make up in quality what may be lacking in quantity. If nothing else, I think I run a pretty broad gamut of different films of different types, from The Magician—a silent, 1926 precursor to Frankenstein—to Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing going up against an evil monster skeleton in 1973's The Creeping Flesh.

Along the way, there are zombies, old dark houses, devil bats, ape fiends, wax museums, haunted stranglers, vampires, witches, alien invaders, invisible dinosaurs, giant monsters, giant rabbits, and a whole lot more.

So, whether you're planning to use this as a viewing guide, or just want to flip through to find out my thoughts on some of your old favorites, dim the lights, grab some popcorn, and prepare for a return trip to the Vault of Secrets. After all, monsters never stay buried for long and we've unearthed a fresh new batch of classic (and not so classic) horror films for your delectation….

The Magician (1926)

Directed by: Rex Ingram

Starring: Paul Wegener, Alice Terry, Ivan Petrovich.

Back when I was still writing the Vault of Secrets column for Innsmouth Free Press, I didn't cover very many silent films for various reasons, even though the imagery of silent horror films has had an enormous influence on horror in general and my own writing in particular. In fact, no silent films made their way into the previous volume of Monsters from the Vault. This is the only one in this volume, but if you're largely unfamiliar with silent horror films, they are well worth tracking down.

I had actually never heard of The Magician prior to seeing a GIF of it on Rhett Hammersmith's Tumblr. The GIF in question—a sculpture of a devilish faun collapsing onto actress Alice Terry—was enough to get me to track down the film. Long considered lost, The Magician didn't get any kind of home video release until it was put out on DVD by TCM in 2011. This is the version I watched.

It's a shame that The Magician isn't better known. While it may never quite reach the Gothic heights of such silent horror classics as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Nosferatu, Faust, Häxan, and so on, The Magician is, at worst, one rung beneath those and, at its best, can give them a run for their money.

Directed by Rex Ingram, who was once called "the world's greatest director," The Magician was shot on location in Paris and Monte Carlo, and in Ingram's studios in Nice, France, giving it an unshakably European feel, a sense of scope and modernity that is denied to many of its stage bound contemporaries, and even the talkie horror films that would follow it.

Ingram adapted The Magician from the 1908 novel of the same name by M. Somerset Maugham, who was, in his turn, purported to have based the titular magician on Aleister Crowley. In fact, Crowley actually wrote a critique of The Magician the year that the novel was released, in which he accused Maugham of plagiarism. Perhaps ironically, the critique appeared in Vanity Fair under the pen name "Oliver Haddo," the name of the magician from Maugham's novel and Ingram's film.

Both film and novel tell the story of Haddo (played by Paul Wegener of The Golem and others), a "hypnotist and magician" who is attempting to use an alchemical formula to create new life. In order to complete his experiment, however, he needs the "heart's blood of a maiden." Enter sculptor Margaret Dauncey, played by Alice Terry, Ingram's wife and frequent collaborator. We are introduced to Margaret before any of the other characters, in the scene that produced the GIF which drew me to the film in the first place.

The massive satyr sculpture that crushes Margaret is the first of many indelible images in the film. Others include an almost Boschian scene of Dionysian revelry which would have been right at home in Häxan, complete with a "dancing faun" who ravishes a girl in front of a decidedly yonic archway, reminding us all that there wasn't a Hays Code yet in 1926.

When Aleister Crowley was accusing Maugham of plagiarism, he listed a variety of works, including The Island of Doctor Moreau. Conspicuously absent from the list is Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, yet the shadow of that novel falls heavy over the cinematic version of The Magician. While the definitive film version of Frankenstein was still several years away, many of the elements of it are already present here, including a climax in an "ancient sorcerer's tower" on a dark and stormy night, not to mention the eponymous magician's diminutive assistant.

Haddo's laboratory may lack the modern amenities and galvanic equipment of James Whale's Frankenstein, but the bones of the monster are already in place. Most Frankenstein films don't end with quite such a brawl as this one does—making good use of Paul Wegener's somewhat hulking physique—though they do often feature the climactic inferno that we see here.

As with most silent films, the music and color tinting do a lot of heavy lifting in The Magician. The version I watched had a score composed by Robert Israel, which matched the events of the film beautifully and felt, at times, a bit like watching Fantasia.

[Author's Note: This entry originally appeared on my blog at orringrey.com.]