Adam Roberts is often described as one of the UK's most important writers of science fiction. He has been nominated three times for the Arthur C. Clarke Award: in 2001 for his debut novel Salt, in 2007 for Gradisil, and in 2010 for Yellow Blue Tibia. He has won the John W. Campbell Memorial Award, as well as the 2012 BSFA Award for Best Novel. Roberts reviews science fiction for The Guardian and is a contributor to the SF ENCYCLOPEDIA. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. His science fiction has been praised by many critics both inside and outside the genre, with some comparing him to genre authors such as Pel Torro, John E. Muller, and Karl Zeigfreid.

Adam Roberts is often described as one of the UK's most important writers of science fiction. He has been nominated three times for the Arthur C. Clarke Award: in 2001 for his debut novel Salt, in 2007 for Gradisil, and in 2010 for Yellow Blue Tibia. He has won the John W. Campbell Memorial Award, as well as the 2012 BSFA Award for Best Novel. Roberts reviews science fiction for The Guardian and is a contributor to the SF ENCYCLOPEDIA. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. His science fiction has been praised by many critics both inside and outside the genre, with some comparing him to genre authors such as Pel Torro, John E. Muller, and Karl Zeigfreid.

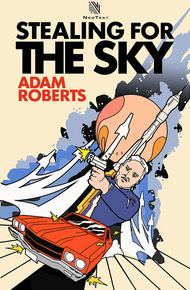

A blistering science fiction thriller by Adam Roberts with the hardboiled edge of Richard Stark's Parker series.

People call him Starman though his name is Fosse. He steals spaceships to order.

In the near future, as humanity colonises the moon and earth's orbital space, scores of shady groups want in on the action: the mob, emerging nations, terrorists, you name it. If you don't have the resources to develop your own space programme, no problem. Starman will steal anything you need, from shuttle components to entire rockets.

On one of his jobs Starman picks up a strange sphere that seems to possess anti-momentum. He's not sure what it is, although it's soon apparent that certain people will go to any lengths to relieve him of it.

When an Irkutski Independence group enlists Starman to swipe an antique Soviet rocket from a Russian space museum, the mistake they make is double-crossing him.

Starman is most definitely not the kind of man you sell out …

Adam Roberts is always surprising and always entertaining, as he is here with this science fictional noir take on the classic Parker novels – in the way only Adam can! – Lavie Tidhar

"intrigue, with action that makes John Wick look like kindergarten"

– Jonathan M"Think Indiana Jones, written by Tom Clancy, and directed by Quentin Tarantino."

– Jonathan C"a smart sci-fi, page turning, adventure story"

– Michael S"Score another win for Roberts, as he writes a short adventure novel in the style of Donald Westlake."

– Pablo1. The Sphere

People called him Starman though his name was Fosse. He had been called it so often it sounded more like his name than his name did. It had started in mockery, though people soon enough discovered it was a bad idea to mock him. Somehow the name had stuck.

Starman had grown up among people who thought the way to get to heaven was through prayer and goodness. From an early age he had figured that the way to get there was using a machine.

He was on his way to steal a piece of such a machine now. Not for his personal use, though. Not for his personal machine. His own, individual and personal dream was a little way off yet. But he would be paid for stealing this machine, and that money would go into a pot for the eventual realization of his dream.

His dream was: escape.

He was a tall man, not broad or hefty but with many lozenge-shaped muscles in his upper arms, with a big chest and pebbles of muscle in his midriff. Skin that looked like it had been vacuum-packed, sucked hard onto his body. Starman had a long chin that curved out, and he had round eyes shelved on prominent twin cheekbones. He smiled very rarely. The tide of his hair had gone out, leaving dotted and short remnants over the top and sides of his head. When he wanted to intimidate the people, he knew how to do that: to draw himself up to his full height, throw out his chest and put his head back so that the punchinella chin was less obviously comical, and the eyes withdrew menacingly. But for the job today he didn't want to intimidate anyone. On the contrary, he wanted the security guy off-guard and dismissive of him. Ideally he wanted him condescending. So today Starman was wearing a delivery driver's jacket much too big for him, and a bad toupee. When his van rolled up to the checkpoint, he tucked his head down so that his big chin was more ridiculously noticeable.

The security guard slid the window of his booth open. 'Where is it?' He meant the permit to enter the facility.

Starman grinned like a fool. He replied that it was, in a small, raspy croak quite unlike his actual voice. 'I lost my voice.'

'What's that?' The guy leaned in.

Starman didn't lean forward. This forced the guard to lean closer to him. It meant Starman's face wasn't visible on the surveillance cam—perched like a bird on the roof of the guard's booth—and it put the guard at a disadvantage. The van and its number had been clocked, of course. Starman didn't care about that.

'Voice,' Starman croaked. 'Lost it. Gone!'

'Why are you whispering, dude?'

Starman held up a tablet—a brand-new top of the range iPad, the kind graphic designers use to perfect their professional sketches. He pressed a button and the device's neutral voice said: I'm sorry I've lost my voice.

'Huh,' said the guard, sitting back a little. 'I still need to see your permit.'

Starman pressed the tablet again. It's here on my pad. Then: it's my sister's pad, it's brand new and real expensive. I got to be careful with it.

The guard leant further forward. 'Your sister's?'

Starman pressed the button: I broke mine, I got to be super-careful with this. Then, after some typing: I need it for my job, but I got to give it back to her, it's brand new. The affectless syllables muttered their way out of the device.

'Just show me the permit,' said the guard.

Starman held the screen at the open driver's-side window, moving it so that it was between his face and the camera.

'That's small,' said the guard. 'Can you make it bigger?'

Starman slammed the screen into his face. The guard reeled back inside his booth, blood leaking from his nostrils. It was such a surprise to him, and the pain was so sharp, that he didn't even make a sound. Starman pushed himself through his van window like a jack-in-the-box coming out. Turning his head to the left, so the camera saw only a back view, he squeezed right in through the open slot of the guard's booth. He flipped the tablet and pushed it hard, so the thin top edge went under the guard's chin and hit his throat, below his Adam's apple.

The guard made a sort of duck-call noise. His hands went up to his neck. The top of Starman's long torso, shoulders and up, were inside the booth with him, crowding the space. In a moment Starman had slipped a zip-tie round the guard's wrists, neatly presented as they were just under his chin. The loose end of the zip-tie had an arrowhead double hook, two barbed flaps of hard plastic. Starman dropped the tablet, and grasped the guard's chin with his left hand, feeling with his thumb for a soft-spot in his gullet, above the Adam's apple. He jammed the end of the cord here, breaking the skin and pushing the hook through.

If the guard's mind cleared sufficiently to think how he might free himself he would find that pulling his tied hands away would yank down agonizingly on his own trachea. The pain and distress would keep him immobilized, trying to keep his hands steady and near his own throat.

Starman pushed the guy back, so that he fell off his stool and into the back corner of the little space. Then he identified the correct button to open the wire-gate entry point.

He turned his head to the right again as he slid back into the driving seat of his van. He drove forward through the open gate.

What had the camera seen? A van, with a certain registration plate. The driver trying to show a screen. Some confusion and the driver leaning in, actually inside the booth. Some struggle maybe? This guy was the sole security guard on duty at this particular facility, a small private concern. If this had been a military establishment, Starman would have needed a completely different way to get inside, but this was lower rent. The guys on the other end of the video feed were like the poor bastard in that booth: minimum wage goons, no particular reason to care what happened inside the facility they guarded. The control room was probably a hundred miles away, in a different state, and processed the feeds of four dozen sites like this one: small private labs, bijoux tech companies that made bespoke items for the aeronautics and space industries. These places were not gold mines, banks or weapons manufactories.

It was possible the guys on the other end of the feed would immediately call the local police, in which case Starman would have maybe a quarter hour to do what he had come to do. Much more likely they would dicker around, try to raise their man on the line, getting puzzled when he didn't reply, check the other feed cams, and eventually—too late—call it in. Conceivably they hadn't even noticed.

The Google Earth map had given Starman a sense of how the facility was laid out. He knew which building he had to get inside. He knew where the cameras were.

Here was one, on a pole. Starman aimed the van at the metal stalk. He didn't have to accelerate very much. The weight of the vehicle gave it enough momentum, as he dinged it, to bend the whole thing through thirty degrees. The security cam was now filming a trapezoid of tarmac and the bottom section of the perimeter fence.

He stopped the van and checked the time. The sun was below the horizon and the sky was a gleaming cyan-blue. A half dozen stars were visible, like shining nail heads holding the sky canvas up. Bats hurtled silently and zigzagged.

Starman stepped out of the van and flopped the empty backpack over one shoulder.

The building he wanted was a single-story prefab, not big—five meters by seven maybe—coin-gray on the outside, windowless. A lit spotlight was fixed above the door, projecting a cone of light over the entrance.

The door had a brick-sized security reader fitted where a keyhole would normally be. Starman didn't have the swipe-card for this.

One of these things would be true: either there was somebody inside, or there wasn't. If there wasn't, Starman would cut a hole through the prefab wall—a much softer material than the reinforced and locked door it surrounded.

He banged on the door. 'Hello? Hello!'

A sound of scraping from inside, like a chair being pushed back. 'Who's that?'

'Security,' Starman called. 'Could you open up please?'

There was a moment's hesitation. Then he heard steps. It was as simple as that. Human beings are always the weakest link in any security system. The person inside might have thought twice before opening the door. Might have called to check why Security was knocking on her door. Might even have asked Starman some further questions. But she didn't do any of that. She was inside a fenced and guarded facility. If this man was at her door, he must be legit.

The bolts flew back like drumbeats, one, two, and the door opened a little way. A pale, upended teardrop of a face appeared in the gap. 'What is it?'

Starman slammed the door open, knocking her back. As he stepped through, she was still in the process of falling—an elaborate, surprisingly slow tumble downwards, her overbalancing, arms out, trying to stop herself hurting too badly as she went down. Then she was on the ground, on her back. Starman had his knee on her sternum as soon as she was on the floor, and, whilst she was still disoriented, he hauled her hands above her head and tied them with a zip-tie. Then he got off her.

'Oh my god,' she said, in a clear voice. She did not sound particularly terrified.

'Stay down, stay quiet,' said Starman, as he scanned the contents of the room. 'If you do, you won't get hurt.' There were two wardrobe-sized computer units, a low table cluttered with electrical gear and tools, a poster on the wall showing superheroes in what looked like different-colored wetsuits, and a huge-faced purple rock troll, maybe, glowering down at them.

'I don't believe this is happening.' She did not sound scared so much as weary. Depressed.

Starman was looking for one thing in particular: a Doerr 88 Satellite Spin Stabilization and Directional unit, a box about the size of a picnic hamper. This was how he made his living. A company, or organization, or perhaps a small country, wanted to put craft into space, but had limited options: they might develop their own versions of the needed technology, or else pay the market rate to those countries that had developed it, like China or the USA. Or they could pay somebody like Starman to steal it for them. This latter option worked out a whole lot cheaper.

The 88 SSD was state of the art: combining a despun antenna with a system gravity gradient stabilization of the total spacecraft, ideal for medium altitude orbits, but also for crafts intended for higher altitude and for Earth-Moon voyage too—or beyond.

Starman's business model was bespoke. When he was a kid, he stole high-end sports cars to order. That business became increasingly tricky and dangerous as anti-theft devices got more and more sophisticated. As a young man, he had stolen a few private jets, again to order. You fly these to a remote place, say a dusty rectangle of land in Nevada, and spend a day, in effect, filing off the serial numbers—which is to say, going through not just the physical wiring of the craft to remove tracking devices, but reprogramming the plane's MCU code. Resetting the whole machine to factory settings and finishing off the day (as dusk winds tourbillon dust columns to blur the view, and the horizon bakes the descending sun a stark lobster red) by spray-painting over any insignia on the hull.

But this was laborious work that paid less than you might think. And Starman's dream had always been set higher. He wanted heaven. He wanted heaven literally.

His interest in this high frontier meant that he acquired a body of valuable expertise. He went to college. He picked up hands-on experience as he thieved. This in turn happened to coincide with what people called 'the second expansion'. After the national space programs of the 20th century had fizzled out, and after 'space' had lain dormant, welcoming but ignored, for decades, a second burst of interest was created by private companies in the 21st. The big governments were content with low-orbit satellites and military platforms, but the caste of billionaires spun out of the unequal economics of this high-powered, low-justice century wanted more than that.

As the billionaires put significant portions of their money into spaceflight and vacuum-living projects, millionaires became interested in achieving something high status. And some small governments wanted to punch above their geopolitical weight wanted high-profile space missions they couldn't actually afford. It created a black market for space tech.

This was where Starman came in.

'I guess that was stupid of me,' said the woman on the floor in a flat voice.

Starman didn't contradict her. He could see the 88 SSD on a waist-high surface in the corner of the room. It took him less than a minute to unplug it and fit it in his backpack, pulling the fabric of the bag around its bulk like fitting a condom.

As he turned back towards the door, he noticed the box.

'Leave the box,' said the woman on the floor. She had turned her head to look at him, and Starman could see that the door had impressed a red bar on her left cheek. She didn't seem to be bleeding.

Starman looked down at her.

'Please,' she said. 'Believe me: you'll thank me. Take the SSD and just go.'

But it is hard to see a box and not want to know what's inside it. Starman walked over to the box. Its lid had a latch on it. When Starman nudged this, it flicked open, the lip popped up and the four sides of the box fell away.

Inside was a sphere. It looked like a bowling ball. A little smaller than a regular ball. Its blackness was illuminated with random scratches of appearing and disappearing light of the sort of blue-green you might associated with the color of Northern Lights. But then the lights faded, and it was an inert, black globe.

'What's this?' Starman asked.

The girl looked up at him, straining her neck. 'We don't know,' she said.

He didn't have time to waste, which meant he didn't have time to interrogate her over this object. Good news for her: Starman had ways of asking questions that put the other person in an uncomfortable position.

The decision to take the sphere took him seconds but when he put a gloved hand on it, something strange happened. He barely touched it and the thing flew off the work surface. It was as light as a ping-pong ball and shot though the air as he brushed it. But as it started to fall, it slowed down. Starman followed it with his eyes. It fell quickly, then more slowly, and then appeared to float to the ground, coming to rest on the floor a yard from the prone woman.

'It does that,' she says. 'Weird, no?'

Starman's first thought was that there must be some kind of device, perhaps something magnetic, inside the globe. 'Is this something you've been developing?' he asked the woman. 'Is it magnetic?'

'We don't know what it is,' she said again.

He couldn't waste any more time. Leaning down, he picked up the sphere, which was light as a feather. He straightened and had lifted it to his waist before it started to feel heavy. That was weird.

He settled the backpack on his shoulders. That at least was reassuringly weighty. Then he took a step towards the door. For the first step the sphere might have been made of polystyrene, so light it was. With the second and third its weight began to make itself felt and by the time he was outside it was so heavy he figured he was going to have to drop it.

He stopped. He considered fitting the sphere inside his backpack. But that had been chosen to fit the SSD precisely, and there was no room. Plan B: he could just leave the globe. He hadn't come here looking for it or anything like it, and he had the loot for which he was being paid. But something about it drew him.

And, oddly, when he started walking again it was, once again, light as a bubble, though by the time he reached the van it was heavy again. Something whacky was going on. He stopped to wrangle the door open, and when he motioned to put the sphere through, onto the passenger seat, it was light again. It rested on the seat, looking innocuous.

Starman slung the backpack into the rear of the van, climbed in the cab and started the motor.

The vehicle started easily, turned and rolled down towards the exit, but again the globe began acting weirdly. Though he was driving on the flat, the strain on the motor increased as he went and Starman was forced to push on the gas. The globe began to sink into the upholstery, compressing the right angle between seat and back.

It felt as though the van was snagged on something. Starman actually looked into his rearview mirror to check nobody was behind him—a cable tied to his pick-up hook, maybe. But there was nothing there.

He stopped the van at the main entrance, and hopped out. The guard's booth was accessible through a door that opened onto the inward part of the compound. The guard himself was still inside, crumpled against floor and wall. He was whimpering. His shirt was bibbed with blood. Starman pressed the button to open the exit gate, hurried back to the van and drove through.

The van rolled forward easily, and the globe was sitting peaceably on the passenger seat. But once again, as he drove down the access road, the engine started struggling, complaining, and the van slowed as if being impeded.

He got to the junction where the access road met the highway and stopped. Away to his left he could see, winking like a solitary Christmas light, a distant police car—just the one, approaching. If it had its siren on, Starman couldn't hear it. Its light splashed red and blue into the shadows of the late dusk.

Starman turned right onto the highway and started to drive away. The same thing happened as before: the van moved smoothly, and then began to sputter and complain. Soon enough he had the gas floored and the engine screaming and the globe was digging so deep into the cushion of the seat that it had almost disappeared.

He had no choice. He had to stop. So he pulled over to the roadside, turned off the engine and all his lights. Then he just sat. The flickering white-blue light grew in his rear-view, and the siren swelled into audibility. The squad car reached the turn-off and swung away up towards the facility.

Starman pressed the ignition and drove away.

He didn't turn on his headlights, and he drove slowly, but the weirdness happened again. Not long, and he had to stop. Soon enough he discovered the way to proceed: if he stopped the van, starting again was easy, though movement grew progressively more difficult the longer he stayed in motion. So he had to stop often, and start over again repeatedly. It didn't seem to matter if he moved slowly away from being stationary, or if he sped away like a drag racer. Either way the van's inertia grew at a steady rate and he was eventually forced to stop again.

It was the globe. Starman couldn't figure how it was doing it, or what it meant—not right then and there—but it could only be the globe. He could have opened the passenger door, pushed it out and driven away, but he chose instead to proceed in this frustrating, laborious way and keep the thing. Whatever it was, it was something unlike anything else he had encountered, and that meant it must be valuable.