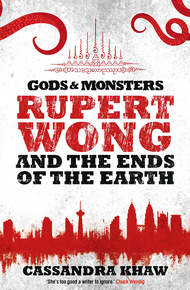

CASSANDRA KHAW is the USA Today bestselling author of Nothing But Blackened Teeth and the Bram Stoker Award-winner, Breakable Things. Other notable works of theirs are The Salt Grows Heavy and British Fantasy Award and Locus Award finalist, Hammers on Bone. Khaw's work can be found in places like The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Year's Best Science Fiction and Fantasy, and Reactor. Khaw is also the co-author of The Dead Take the A Train, co-written with bestselling author Richard Kadrey. Their latest novel, The Library at Hellebore, will be out in July 2025.

For a man who started a celestial war, Rupert Wong, Seneschal of Kuala Lumpur and indentured cannibal chef, isn't doing too badly for himself.

Sure, his flesh-eating bosses inexplicably have him on loan to the Greek pantheon, the very gods he thrust into interethnic conflict. Sure, the Chinese Hells have him under investigation for possible involvement in the fracas. But Rupert is alive.

For now.

Really, it could be slightly worse.

I dare you not to fall in love with Rupert Wong, who moves across the pages of this trilogy like a classic hardboiled character in a magical Kuala Lumpur filled with gods and monsters. I loved it as soon as I read the first chapter, and I bet you will too! – Lavie Tidhar

"If Rupert Wong doesn't become the God of Rapidly Extemporised Plans, it won't be through lack of trying. Or possibly God of Great Personal Jeopardy. Whichever seat in whatever pantheon he finally attains, he deserves it, because reading Rupert Wong is a divine experience."

– Jonathan L. Howard"Rupert Wong, Cannibal Chef is one of those books that you have to pick up when you find it, if only to see whether or not the title is screwing with you. Bottom line: if you can handle the profanity and grotesque content, you just may find this one to your liking..."

– Manhattan Book Review"Can I call you back? Cooking for dear life here. I—yes, no—yes, I guess it's an euphemism. No? Yes. I—"

Oil fountains through the air as my new iPhone performs a ten-point dive into the wok, slipping from where it was wedged between cheek and shoulder to bury itself in a hell of pumpkin croquettes. I jerk back away from the splatter and sizzle of a few thousand ringgit gone the way of good bacon.

There is no time to curse, though, or even think. I'm on a tight schedule here. I toss the pan a few more times, drop it on the counter, and then spin about to slice up slivers of large intestine. It's definitely not the best prepared length of meat my knife has seen. Bits of decomposing waste material blink at me from between puckered folds, shot through with dying tapeworms like fistfuls of wanton noodles. But the boss says the detritus of the human digestive system gives character to a meal. Who am I to argue with the monster who pays my rent?

(He has ghoulish tastes, ang moh. Get it? Get—anyway.)

Across the stage, my opponent is in trouble. He's standing impaled in the spotlights like a Scandinavian Jesus before a Roman tribunal, fishmouthing all the while. In front of him, set in a bed of wilting roses, are the remains of a Brazilian pornstar, megawatt grin sutured in place, final million-dollar erection jutting proudly from a death-bruised pelvis.

The crowd is chanting, pounding its feet. They want him to do something with that colossal penis. Suck it, cut it, flay it, pickle it in chocolate syrup and make it into a meat eclair—anything, so long as he does it dramatically. But language barriers and terror keep the Swede from capitulation. Instead of putting on a show, he clumsily saws off a leg and scuttles off to the oven. Bad move there, Thor. Briefly, I contemplate volleying advice in his direction, but it's do-or-die here.

Literally.

I turn back to my own counter. I've got my own porn star neatly split into eight portions. There's barely any blood on the wood. Most of it's been drained into separate containers for later use in my sambal-laced black pudding and the rosewater popsicles I've got planned for dessert. The ghouls of Kuala Lumpur might be sophisticated by the standards of their species, but they're still bloodthirsty predators. No gore, no talk.

I cut the epidermis from the stomach with a scalpel, before carefully smearing the exposed muscle with salted egg yolk, mango extract, and a glazing of soy. Then I replace the skin, sew it together at the ends, drizzle the surface with caramel and put the amputated torso in the oven. If this was any other situation, I'd have marinated the meat for at least a day, but c'est la vie, as the Europeans say.

Or something.

The gong booms. Two hours. Behind me, I hear the Swede swear, hear a pan clatter onto the floor, and something sizzle through the air. Another yelp, louder, pain-whetted. Guan Yin help me, this isn't going to end well for our blond friend.

I peek quickly at the audience as I go for the peeler and the bone saw. Our spectators are gathered in concentric rings around the stage, identities concealed in the penumbra, craning forward like dogs on a leash. They've stopped talking entirely now, and it's disconcerting, I tell you. You never really notice the sound of breathing until it is gone.

Of course, I probably shouldn't be listening for it. I should be hacking—carefully—through this perfectly-shaped cranium. And maybe doing something with the scalp, even if the whole concept is ethically questionable.

What am I saying? Everything I'm doing is ethically questionable.

* * *

It goes better than I expected.

Not only do I extract the brain intact, I am ameliorated of some of my lingering existential guilt. The porn star's gray matter is a road map of early-death risks: brain lesions, abscesses, even a tumor, no larger than a small child's tooth. He was going to go, anyway, right? Right.

The slurry of neural tissue goes into a pan with ghee and caramelized onions, turmeric and chilli and garlic paste. Almost instantly, the fat begins to crackle, and I watch it like a hawk, pulling the pan away the instant the meat begins to smoke. Too much time on the fire, and you get charcoal. Too little, and it's just an unappetizing mush. (Don't ask how I know these things. We all sacrifice something different for our careers.)

A quick glance at the clock informs me that I've about half an hour left, and I spend it injecting globs of lime-laced honey into chilled eyeballs before plating it carefully amid passion fruit foam and clots of lemon curd.

The minutes slip by.

"Time."

I drop my utensils with a clatter of iron, jumping back a heartbeat before a lithe, black shape bumps against the back of my knees. The Swede does not and I hear a whine of pain, sharp, quickly cut down to ragged gasps. I glance sideways: someone's split his palm open and blood is pooling on the stage. I lick my lips nervously. Not good.

The spotlight comes back on, the phosphorescent blaze drawing all eyes up to an alcove in the walls. Like everything else with the ghouls, the ornate balcony is strange, a bizarro arrangement of whatever might have interested the maker at the time: Parisian balustrades, Roman columns, a patchwork of Banksy paintings redone in polished sea glass.

There's a figure staked in the light, his silhouette haloed against a revisionist nightmare of the Water Margin, intimating a saintliness that I know is undeserved. If there's anyone in this spectacle of murderers that's a proper bastard, it's the Boss. He grins, all teeth, slicked-back hair and arrogant posture, the Armani-armed image of Malaysian patriarchy. He's power and he knows it.

"Two contestants walk in. One walks out."

A murmur of appreciative laughter slithers through the crowd.

"The winner will receive all he desires"—liar—"and the loser will regret his inadequacy."

The audience chuckles again. Terror batters against my temples. No matter how many times I've been conscripted into this horror show, it still gets to me. I think it's the theatrics, the aping of normalcy, the pantomime of reality talk show innocence. I wipe my fingertips along my gore-streaked apron and straighten my back, bladder clenched against the escalating dread.

"Our judges"—more polyps of light break against the murk, and three new faces become illuminated: blandly attractive, utterly forgettable—"will now sample the meals. The participants will be judged on taste, timeliness, versatility, and command of ingredients."

Another susurrus of noises, now with an undercurrent of savage. The Swede's eyes are glazed, his forehead slick with sweat, although in retrospect that could be blood loss rather than terror.

I walk my gaze over his flotilla of food: only seven dishes, not the prescribed nine. No desserts, either. Around the ledge of his shoulder, I spot his biggest error: he's amputated the penis but done nothing significant with it, leaving the organ to lay deflated in a puddle of congealing cranberry sauce. You'd think he'd be wise enough to make it the centerpiece.

Yeah, I can't see this ending well.

"Will the contestants bring their dishes forward?"

* * *

I win.

Of course I win.

I've never not won. We wouldn't be having a conversation if I'd ever lost. The terms of the tournament are simple if never advertised, a de facto knowledge secured through survival.

The winner acquires employment. The loser gets served on a plate.

* * *

There's plenty that I dislike about Chee Seng. His haircut, his voice, his indifferent hygiene, his penchant for public earwax excavations. But I can't fault his professional technique.

Chee Seng is fast and very, very discreet. The Swede barely notices his exsanguination. He surrenders the barest expulsion of air, almost a sigh but infinitely more ephemeral, before he sags onto his knees, Chee Seng's arm suddenly crossed over his breastbone. And then carefully, with more strength than you'd anticipate from a chubby Chinese man in a wife-beater, he guides the giant down. Blood tendrils across the stage, an abattoir masterpiece.

The Scandinavian spasms—once, twice—before he begins to thrash, bellowing like a cow, but no matter how hard he struggles, his bulk stays pinned under an expertly positioned knee. Chee Seng drones scriptures with a practiced flippancy; the ghouls demand halal treatment of their meats, even if their preferred cuisine itself is sacrilegious in every Abrahamic faith. I make eye contact with Chee Seng, who shrugs. The air colors with the stink of urine. The crowd roars.

Eventually his quarry's convulsions subside, muscles slackening. The odour of piss picks up a fecal undertone, and I grimace. Hopefully, they'll have Chee Seng prepare the carcass as well, an ordeal that he tolerates but I flat-out loathe.

As the last of the Swede's life bubbles away, Chee Seng and I raise our gazes, like Dobermans trained to a nod. His smile is patronizing, calculated. I tense.

"Thank you for the assistance, Chee Seng."

Motherfucking chee bye chui.

"Rupert." And here, the Boss's grin spreads. The seams at the corners of his lips undo, widening, revealing jaws that span his head. "If you'd like to do the follow up..."

No. No, I don't. "Y-yes, boss. But Chee Seng's way better than—"

"We prefer the personal touch of a chef." His voice is an oratory wet dream, the baritone of a radio announcer or a successful politician, and it booms across the auditorium without enhancement. Despite the honeyed enunciation, the subtext is clear: there's no room for negotiation here.

"Of course, boss." Asshole.

He maintains his grin. Ghouls aren't telepathic, but I'm putting no effort into disguising my revulsion. The boss loves dissatisfaction in his employees, though, especially since he knows mutiny is an empirical impossibility. So, for now, we're cohabiting a page.

Irradiated by halogen, the last breathing human in an ocean of the dead, I grab the tools of office—bone saw, cleaver, a toolbelt of kitchen knives in different sizes—and march towards the fallen behemoth. If anyone ever tells you that the life of a cannibal chef is glamorous, punch them in the scrotum for me.