Internationally bestselling author Mercedes Lackey has written over fifty novels and many works of short fiction. In her "spare" time she is also a professional lyricist and a licensed wild bird rehabilitator. Mercedes lives in Oklahoma with her husband and frequent collaborator, artist Larry Dixon, and their flock of parrots.

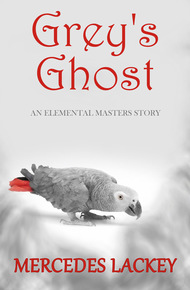

Grey's Ghost is a short story set in the Elemental Masters world, an alternate history where magic exists and mages can control air, water, fire, and earth. Two young mages, along with a clever and gifted parrot, discover that things are not always as they seem.

I've been a fan of Mercedes Lackey since her first Valdemar novels were published, and am delighted that she contributed Grey's Ghost, a short story from her Elemental Masters series. Mercedes is one of the seminal authors in YA fantasy, and it's a treat to have her join us in this StoryBundle. – Anthea Sharp

"As a fan of Mercedes Lackey's Elemental Masters series, I love finding small tidbits that add to the entire universe of her tales. This just adds that much more flavor and variety to her overall series."

– Sarah C.Grey's Ghost

When Victoria was the Queen of England, there was a small, unprepossessing school for the children of expatriate Englishmen that had quite an interesting reputation in the shoddy Whitechapel neighborhood on which it bordered, a reputation that kept the students safer than all the bobbies in London.

Once, a young, impoverished beggar-girl named Nan Killian had obtained leftovers at the back gate, and most of the other waifs and gutter-rats of the neighborhood shunned the place, though they gladly shared in Nan's bounty when she dared the gate and its guardian.

But now another child picked up food at the back gate of the Harton School For Boys and Girls on the edge of Whitechapel in London, not Nan Killian. Children no longer shunned the back gate of the school, although they treated its inhabitants with extreme caution. Adults—particularly the criminal, disreputable criminals who preyed on children—treated the place and its inhabitants with a great deal more than mere caution. Word had gotten around that two child-pimps had tried to take one of the pupils, and had been found with arms and legs broken, beaten senseless. Word had followed that anyone who threatened another child protected by the school would be found dead—if he was found at all.

The two tall, swarthy "blackfellas" who served as the school's guards were rumored to have strange powers, or be members of the thugee cult, or worse. It was safer just to pretend the school didn't exist and go about one's unsavory business elsewhere.

Nan Killian was no longer a child of the streets; she was now a pupil at the school herself, a transmutation that astonished her every morning when she awoke. To find herself in a neat little dormitory room, papered with roses, curtained in gingham, made her often feel as if she was dreaming. To then rise with the other girls, dress in clean, fresh clothing, and go off to lessons in the hitherto unreachable realms of reading and writing was more than she had ever dared dream of.

Her best friend was still Sarah, the little girl from Africa who had brought her that first basket of leftovers. But now she slept in the next bed over from Sarah's, and they shared many late-night giggles and confidences, instead of leftover tea-bread.

Nan also had a job; she had discovered, somewhat to her own bemusement, that the littlest children instinctively trusted her and would obey her when they obeyed no-one else. So Nan "paid" for her tutoring and keep by helping Nadra, the babies' nurse, or "ayah," as they all called her. Nadra was from India, as were most of the servants, from the formidable guards, the Sikh Karamjit and the Gurkha Selim, to the cook, Maya. Mrs. Helen Harton—or Mem'sab, as everyone called her—and her husband had once been expatriates in India themselves. Master Harton—called, with ultimate respect, Sahib Harton—now worked as an advisor to an import firm; his service in India had left him with a small pension, and a permanent limp. When he and his wife had returned and had learned quite by accident of the terrible conditions children returned to England often lived in, they had resolved that the children of their friends back in the Punjab, at least, would not have that terrible knowledge thrust upon them.

Here the children sent away in bewilderment by anxious parents fearing that they would sicken in the hot foreign lands found, not a cold and alien place with nothing they recognized, but the familiar sounds of Hindustani, the comfort and coddling of a native nanny, and the familiar curries and rice to eat. Their new home, if a little shabby, held furniture made familiar from their years in the bungalows. But most of all, they were not told coldly to "be a man" or "stop being a crybaby"—for here they found friendly shoulders to weep out their homesickness on. If there were no French Masters here, there was a great deal of love and care; if the furniture was unfashionable and shabby, the children were well-fed and rosy.

It never ceased to amaze Nan that more parents didn't send their children to the Harton School, but some folks mistakenly trusted relatives to take better care of their precious ones than strangers, and some thought that a school owned and operated by someone with a lofty reputation or a title was a wiser choice for a boy-child who would likely join the Civil Service when he came of age. And as for the girls, there would always be those who felt that lessons by French dancing-masters and language teachers, lessons on the harp and in water-color painting, were more valuable than a sound education in the same basics given to a boy.

Sometimes these parents learned their lessons the hard way.