Brian Herbert, the son of Frank Herbert, is the author of numerous New York Times bestsellers. He has won several literary honors and has been nominated for the highest awards in science fiction. In 2003, he published Dreamer of Dune, a moving biography of his father that was nominated for the Hugo Award. After writing ten Dune-universe novels with Kevin J. Anderson, the coauthors created their own epic series, Hellhole. In 2006, Brian began his own galaxy-spanning science fiction series with the novel Timeweb, followed by The Web and the Stars and Webdancers. His other acclaimed solo novels include Sidney's Comet; Sudanna, Sudanna; The Race for God; and Man of Two Worlds (written with Frank Herbert).

Bruce Taylor, also known as "Mr. Magic Realism," writes magic realism and surrealism, as well as spiritual works. He is the author of The Final Trick of Funnyman and Other Stories, Edward: Dancing on the Edge of Infinity, Mr. Magic Realism, and Mountains of the Night. His book Kafka's Uncle and other Strange Tales was nominated for the &Now Award for Innovative Writing. Bruce has been writer in residence at Shakespeare & Company, Paris, president of the Seattle Writers Association, president of the Seattle Freelances and co-director of The Wellness Program at Harborview Medical Center.

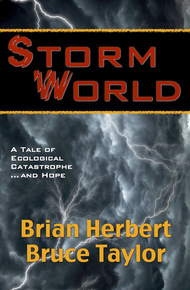

After the Greenland ice cap suffers an abrupt and catastrophic collapse, Earth's climate suddenly changes, turning the planet into a horrendous stormworld. Against this backdrop, men and women in the Cascade Seed Repository valiantly struggle to protect the food supply of civilization....

Brian also wrote STORM WORLD with Bruce Taylor, a gripping story about the survivors of a global climate catastrophe, fighting to defend one of the last seed banks. Bruce is also known as "Mr. Magic Realism," a fixture of the Pacific Northwest writing community—very distinctive in his white suit. – Kevin J. Anderson

In a sudden and shocking die-off of humanity, only five percent of the world population remained. Bodies piled up so quickly that they were usually left to the elements for disposal. Among the clusters of survivors, new and often violent social groups formed. London, Paris, New York, Seattle, and other major cities became burned-out ghost towns, ruled by roving bands of brigands. These armed gangs even terrorized impoverished people in the countryside, who were barely surviving on decimated food resources.

All over the world, religious fanatics bred. Every major religion became dominated by a radical belief system, as the remaining population sought explanation and solace for what had happened. Few knew how to cope with the horrific events occurring all around them, and suicide was, by far, at the highest level in history.

In America and other western nations, fanatical Christians pointed to end-of-the-world predictions made in the Book of Revelations of the Bible. Numerous religious cults formed enclaves in remote locations to survive the ongoing cataclysm, and to await the Second Coming of Jesus and the Rapture.

It was as if every human killing element on the planet had been unleashed at once—even worse than the ten plagues of ancient Egypt. Immense disasters affected the land, the sky, and the water, causing starvation and pandemic outbreaks of disease. There were floods, earthquakes, ferocious winds, and war, on a scale never known before. In the aftermath, a sickly, smoky sky covered most of the world, blocking the sun. On those rare occasions when the sun came out, people stared at it in awe, sometimes blinding themselves in the brilliance, as if thinking it was the light of God, signifying their rescue. But no salvation was imminent, only dismal, squalid times, growing worse by the hour. All of Earth had become what used to be known as the "third world"….

As our story begins, only ragtag remnants of legitimate governmental agencies remain, and militias are poorly armed. Overseeing it all from the remains of the United States is Conelrad, a fledging government of international scientists that is trying to make decisions for the welfare of the entire planet, and not for particular regions. But these valiant men and women are essentially powerless, representing the withering hope that some sense of normalcy might return one day. The improvised government has very little real influence, and only limited paramilitary capabilities.

A Promise of Protection

Abe Tojiko's stomach growled. Still hungry. Always hungry. Looking in the mirror this morning, he saw the taut, stretched skin, the sunken brown eyes and prematurely gray hair. Had he ever really been overweight? He had lost nearly a hundred pounds on his six-foot-one frame, and barely weighed 150 pounds. From constant stress and lack of sleep, shadows had set in beneath his glowering, haunted eyes. Only thirty-eight, he felt twice that age.

With a deep sigh he tried to put the depressing thoughts aside, and went downstairs to check the seed storage chambers, where he monitored the critical humidity and temperature settings. So far, the electrical problems they'd been having had only affected some of the interior doors—God help them if the exterior blast door was ever breached by intruders, or if the seed vault temperatures varied from where they were supposed to be.

Soon his thoughts drifted off. He had worked there so long that he could hardly remember his prior life, which seemed like a distant, halcyon time, a fleeting dream. His pretty wife, three children, his parents, a brother, a sister … how long had it been since he'd seen them, just before they were all killed? Three, or was it four years?

Halcyon was a comparative word. There had been severe climatic fluctuations in those bygone days with his family, causing Abe to move them to higher ground to avoid the immense coastal and river floods that wiped out cities, towns, and crops, relegating entire landscapes to oblivion. He had used his scientific knowledge to select a region where the winds were not expected to reach the dangerous velocities that had been seen in many regions of the world. He selected Beaumont in northeastern Wyoming, a small town at an elevation of 4400 feet, sheltered from the prevailing winds by a mountain range. All available information told him it would be safe there.

After assuring himself that they were all secure in their new lives, Abe returned to his job at the seed bank in Washington state. But a month later, a storm with winds exceeding 350 miles per hour hit northeast Wyoming, scouring the land, turning the once-pristine region into a hellish, lifeless blast zone. Afterward, Abe had only one family, his fellow employees in the Cascade Seed Repository—a facility that was built into blasted-out mountain bedrock.

Now through thick glass walls on the lowest level of the facility, he saw two men and a tall, blonde woman in adjacent chambers, monitoring the precious treasure house that contained every key plant seed in the world, along with a broad selection of tubers, roots, and bulbs. With this raw material, they could recreate everything from desert palms to tundra grasses, and even a number of flowers that served no purpose beyond their physical beauty.

The blonde glanced at Abe, but she did not smile. They were not lovers anymore. Belinda Amar had gone on to Jimmy Hansik, a former body-builder who performed general maintenance, but who had made a number of serious mistakes, causing valuable seeds to be endangered. He should have been fired or reassigned, but had a charming way of convincing Director Jackson that the problems were not his fault. A total of six employees lived and worked in the huge, bunker-like facility, and they didn't always get along.

Employees.

Abe mused over the word, as he made an entry in a hand-held datacube. Like "halcyon" and "family," the word didn't mean what it used to. Most of the time, he felt more like a prisoner than an employee.

Immense environmental disasters had a way of destroying not only habitats, but also the old ways of thinking and saying things. Inside the bombproof, stormproof seed storage facility no worker had received a paycheck for more than ten months, but everyone kept going anyway, surviving and adapting, trying to forget what they had lost.

Behind Abe, an interior door opened, but made an odd, squealing noise that Jimmy had not diagnosed yet. Abe felt a sensation of pressure change. The stocky, dark-skinned Director of Operations stomped in, a perpetual frown on his gray-bearded face. He wore a white laboratory smock with chemical stains on it. "New message from Con," he said, waving a printout in the air.

Benitar Jackson was referring to Conelrad, what the remnants of the United Sates government called itself, after the name of America's first emergency broadcasting system. It was an acronym for Control of Electromagnetic Radiation. The federal government, which once employed millions of people, was only a shadow of its former self. In its place, a skeleton administration of scientists operated from a mountainside bunker in Maryland, sending out queries and orders via a satellite communications system that hung on by only the barest technological threads. Of the satellites in orbit, some of the crucial ones were non-operating, for lack of shuttle repairs. The communications were getting spottier and spottier. Many messages did not get through at all.

Abe read the dispatch. It was brief but urgent:

Cascade Seed Repository:

You are now the last undamaged seed bank in the world. We intend to send a military force to protect you, but circumstances make it impossible to promise a date. In the meantime, notify all personnel to arm themselves and remain on the highest state of alert. Keep in mind that weather-tracking data (and all other information) will be intermittent due to ongoing technical problems. As for the electrical problems you cited, we have no suggestions. You will have to figure them out on-site, giving priority to seed vault temperatures.

—Conelrad HQ

"Guess we have job security now," Abe said. "Say, isn't it about time you distributed those firearms you've been hoarding?"

Jackson's bright green eyes flashed. "I'll decide when the time is proper!" He snatched the printout from Abe and stalked off.

The Director, whom Abe referred to as "Top Seed," had not smiled for a long time, and Abe worried about the older man's mental and physical health. Even faced with the tyranny of the Director, Abe always tried to see the good in him, the way he'd dedicated his life to such an important cause. As for Abe, even through the most difficult of times he cultivated his own sense of humor, as if tending to a precious plant. He found laughter therapeutic, enabling him to get through problems.

Entering the chamber through a thick glass door, Belinda grimaced and asked, "Couldn't you show him just a little more respect?"

"I was just kidding him. He knows I respect him."

The tall blonde scowled. "Be careful. If you go too far he could just eliminate you and build a robot to take your place. I've seen him tinkering in his workshop late at night."

"Yeah, well if he did that, he'd miss me. I provide a lot of the entertainment around here … not only for him, but for the others. I'm the voice of sanity, keeping people on their toes, and he knows it, no matter what he says."

"Benitar is nuts, you know," she said. "and smart, with that personal escape capsule he has for himself, kept where the rest of us can't get to it."

"I'd rather call him focused than nuts," Abe said. But there were troubling aspects of the Director's personality, he admitted to himself, including things he didn't bother to explain to any of the staff. Before the weather went into the deep freeze, the wealthy Jackson had designed and built a rocket-propelled capsule, which he had fitted into a chamber on the upper level, donating his own funds to the government for this, and supposedly getting their approval. Calling it the "emergency seed-evacuation capsule," Benitar said he had a sampling of seeds stored on board, and that the rest of the craft was only big enough for one person. None of the staff had ever been permitted to see the vessel, nor did they know the access and launch codes.

"It gives me an uneasy feeling just knowing it's up there," Belinda said, looking upward, "while the rest of us poor saps don't have anything like it."

He looked at her intently, and changed the subject, since matters involving Benitar were often pointless and frustrating to discuss, because no one could do anything about them. "I hear you went topside this morning," Abe said. "What's the weather like out there?"

"White on the ground, gray in the sky."

"Same as usual."

She shook her head. "Deeper snow and a darker, lower cloud cover. Wind is whipping up. Looks like we're in for another blizzard—Who knows? Maybe the mother of them all."