Burl Barer is a Edgar Award winning author and two-time Anthony Award nominee with extensive media experience. Garnering accolades for his creative contributions to radio, television, and print media, Barer's career has been highlighted in The Hollywood Reporter, London Sunday Telegraph, New York Times, USA Today, Variety, Broadcasting, Electronic Media and ABC's Good Morning America.

Burl Barer hosts the award winning Internet radio show, TRUE CRIME UNCENSORED with co-host, show business legend Howard Lapides, on Outlawradiousa.com, and TRUE CRIME CLASSICS with famed attorney Don Woldman.

True Crime Books

A TASTE FOR MURDER

BODY COUNT

HEAD SHOT

MOM SAID KILL

BROKEN DOLL

FATAL BEAUTY

MURDER IN THE FAMILY

1982: Oregon businessman Phil Champagne died in a tragic boating accident off Lopez Island, Washington. He was survived by one ex-wife, four adult children, an octogenarian mother, and two despondent brothers. Phil didn't know he was dead until he read it in the newspaper. All things considered, he took it rather well.

1992: Washington State restaurateur, Harold Stegeman, famous for his thick juicy steaks, is arrested by the United States Secret Service for printing counterfeit hundred dollar bills in a tiny Idaho shed. In addition to the bogus bills, Stegeman has a fraudulently obtained United States passport, a fabricated Cayman Islands driver's license, and Phil Champagne's fingerprints.

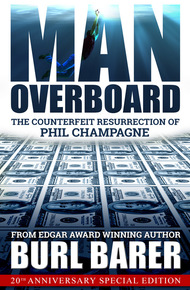

A mind boggling blend of fraud, deception, trickery, lies and fine-prime-rib, MAN OVERBOARD was nominated BEST TRUE CRIME BOOK OF THE YEAR by the World Mystery Convention, and universally praised as the most laugh-filled book in the genre's history.

I included this to lighten the mood a little, and because it's a perfect example of a book that would make a great movie – but that really happened. Con men, insurance fraud, faked death… this one has it all and is told in a manner that is both compelling and entertaining. – David Niall Wilson

"Crisp as a freshly printed C-note. Exceptionally clever and vastly entertaining!"

– Lee Goldberg, author, screenwriter and television producer"Barer does it again! A deft and dazzling display of solid research and rapier wit—a must for all true crime aficionados."

– Gary C. King, author of To Die For"True crime at its best. … Barer has undeniable talent, pizzazz and imagination!"

– Jack Olsen, bestselling author and award-winning journalist…but how much adventure is free from all taint of coincidence? Coincidences are always coinciding—it is one of their peculiar attributes; but the adventure is born of what the man makes of his coincidences.

—Linda Charteris

The Man Who Could Not Die

…And when We deliver him to dry land, then does he compromise.

—The Qur'an

Phil Champagne looked death in the face and found it decidedly unattractive. The .45 automatic aimed at his head, clutched in the angry grip of his "good pal" Raul, was partially responsible for his negative response.

"I'm going to kill you," Raul said with such heartfelt emphasis that Phil didn't doubt his sincerity. "You are a dead man!"

Raul had that part right, but Phil wasn't about to explain. Besides, there wasn't time. Raul's finger was already tightening on the trigger.

***

Phil Champagne's life didn't flash before his eyes when he first died August 31, 1982, in a tragic boating accident off Lopez Island, Washington. He was fifty-two. Champagne was survived by his wife of twenty-eight years, four grown children, an octogenarian mother, and two despondent brothers. Phil didn't know he was dead until he read it in the paper. All things considered, he took the news well.

Standing six foot two, 205 pounds, wearing a Ronald Coleman mustache and demeanor to match, Phil Champagne is a well-aged, blue-eyed, Errol Flynn-style swashbuckler who appears as if he should be starring in an RKO Falcon movie with George Sanders or Tom Conway.

"Don't call me Harold Stegeman." The request is polite, yet firm. There is a mischievous twinkle under the graying brows of the former Harold Stegeman, known to some as Frank Wincheski, known to yet others as Peter Donovan.

"My name is Phil Champagne. I'm pleased to meet you." I was born June 30, 1930, and died in a tragic boating accident in August of '82, in the waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca."

Before the accident, Phil Champagne's adult life had been, in a word, average. In two words, dull and boring. Death—a single splash followed by silence and pursued by searchlights—changed everything.

"There are no words adequate to describe the intoxicating sense of liberation I experienced when I realized I was dead. It was the unexpected answer to an unspoken prayer," admitted Champagne, now in his early sixties. "In the first heady rush of what was perhaps trauma-induced delusion, I decided to be the one thing in death that I had never been in life—an adventurer."

The Secret Service and the FBI prefer the term "convicted felon," although Champagne did not spend twenty-one months in a minimum-security federal prison for faking his death.

"I didn't fake it," insists Champagne. "I simply didn't contradict it."

**

Why would a respected Portland, Oregon, businessman with an essentially crime-free adult life, an excellent career, but otherwise lackluster existence, allow his family, friends, and business associates to believe he had drowned in an accidental fall from a sailboat?

"Having lost my life, I had nothing to lose," said Phil. "I figured no one would starve to death if I wasn't around. I was leaving my wife and kids, but she didn't like me anyway, the children were grown…" Phil's voice trails off. "And no matter what Special Agent Goodman thinks, it wasn't an insurance scam."

Neil Goodman, special agent in charge of the Secret Service office in Spokane, Washington, went public with his emphatic disagreement shortly after Champagne's controversial incarceration.

"Our investigation has determined that Mr. Champagne apparently faked his own death to facilitate an insurance fraud," Goodman delineated to reporters on May 1, 1992. "At least two policies paid out and there may be others we don't know about at this point. At least two other men, including one of Champagne's brothers, were aboard and presumably were involved in the fraudulent report."

Presumptions are one thing, indictments another. After extensive investigation into the matter by law enforcement agencies, no criminal charges were filed against either Mitch Champagne, Phil's older brother, or John Champagne, his younger brother. Phil Champagne died fair and square.

"Honest to God," insists exasperated Phil Champagne, "the Secret Service could win the conclusion-jumping competition in the Olympics. Just because Mitch had a one-and-a-half million-dollar policy on my life doesn't mean he had anything to do with my death. The policy wasn't his idea in the first place, and it sure as hell wasn't mine."

"Phil is telling the truth," remarked Oregon insurance agent and real estate developer Ed Grass. "I'm the one who suggested that Mitch take out what's called Key Man insurance on Phil."

Personable and gregarious with a slight build and snappy goatee, Ed was introduced in the 1970s to the enterprising Champagne brothers by Gresham attorney Don Robertson.

"I was anticipating a nice little commission for selling Mitch the insurance," recalled Grass, "but Mitch decided to get the coverage from Federal Kemper (Life Assurance Company) with whom he was already doing business."

So it was simply prudent business advice that had convinced Portland real estate developer William M. "Mitch" Champagne to purchase a $1.5 million policy on his brother, Phillip, whom he had hired to oversee his rapidly expanding construction empire.

When Phil Champagne disappeared without a trace into the dark, cold waters off the San Juan Islands, Federal Kemper was understandably reluctant to release the money without a recovered body. Mitch demanded payment from Kemper on November 12, 1982 and filed suit to collect in May 1983. A settlement was reached, and in November 1983, Federal Kemper paid Champagne's company $700,000.

According to court documents, "Federal Kemper paid less than the face amount of the policy in the context of substantial uncertainty in the fact of Phillip Champagne's death."

When Phil turned up alive and imprisoned in 1992, the insurance company sued Mitch to recover, claiming a settlement condition required Mitch Champagne to repay the money if his brother was ever found alive. Mitch Champagne resisted the suit because a seven-year "enforceability period" had expired before it was filed.

"Mitch Champagne first learned his brother was alive when Federal Kemper served him with a summons for the insurance company's lawsuit," explained his lawyer, Henry Kantor, of Portland. "Mitch's reaction upon learning his brother was alive was absolute astonishment, which soon gave way to anger."

While Federal Kemper would appreciate having the money returned, Kemper's legal representative, Peter Richter, acknowledged that the insurance company made no claim of fraud in its lawsuit against Mitch Champagne.

While Mitch had been devastated by his brother's death, Phil's high-profile resurrection added legal insults to emotional injury.

"Mitch finds this entire situation humiliating and embarrassing," elaborated Mitch's attorney, Henry Kantor. "He lost his brother twice: once when Phil fell overboard and again when he resurfaced as a criminal. After ten years of grieving over the loss of his younger brother, he discovered that he had been deceived. Mitch is a victim of Phil's deception and, as far as I know, the brothers haven't spoken since Phillip turned up alive."

When the unexpected resurrection of Phil Champagne hit the headlines, the mavens of media collided in the halls of justice. Tabloids, talk shows, and first-run syndication television productions pushed the strange case of Phil Champagne to the top of their most-wanted list. Everyone wanted a salable piece of the not-so-dead deceased.

Including his two bereaved daughters.

Kathy and Renee, a Champagne pair of opportunistic offspring, steadfastly refused to grant even the most minimal press interviews. The reason cited for their icy silence was far from their Uncle Mitch's understandable aversion to public humiliation—they wanted money.

Barbara LeHew Fraley, a longtime companion of Harold Richard Stegeman of Hayden Lake, Idaho, had never heard of Phil Champagne, his brother Mitch, his daughters Kathy and Renee, or Federal Kemper Life Assurance Company. From October 1987 until debts and overhead put them out of business in 1990, she, Harold and her five children from a previous marriage had run Barb's Country Kitchen Restaurant along State Route 3 between Shelton and Bremerton, Washington.

On November 6, 1991, Harold, Barb, and her son, Richard, stopped for breakfast in Ritzville, Washington, at Perkins Restaurant. Located sixty miles southwest of Spokane along Interstate 90, Perkins has built its reputation on pancakes. After a pleasant meal, Barb paid for their ticket with a hundred dollar bill Harold had given her.

It was counterfeit.

Dragged from the pancake house in handcuffs, Barb pleaded ignorance. Harold went home to destroy evidence.

He failed.

Four months later, on Thursday, March 12, 1992, a state department investigator obtained a warrant to search the home of Harold Stegeman. While searching Stegeman's briefcase for evidence of Stegeman's identity, agents found a negative of a seal used on U.S. currency plus other evidence linked to counterfeiting. What the State Department had initially been looking for was Stegeman's passport.

They had already determined that a Harold Richard Stegeman had been born at University Hospital in Coral Gables, Florida, on June 20, 1937, to Paul and Marie Stegeman. Paul Raymond Stegeman and the former Marie Elizabeth Leugers, both from Hamilton, Ohio, had migrated to Miami eight years earlier and resided at 3622 SW 25th Street. Paul was the proud proprietor of Stegeman Jewelry Store, specializing in watch repair.

Harold Stegeman was a student in the third grade at St. Theresa Elementary School when lung problems compelled him to spend seven days in Miami's Jackson Hospital. The State Department investigation revealed that Harold Stegeman died on November 3, 1945, at the age of eight years, four months, and fourteen days.

State Department investigators suspected that the adult male calling himself Harold Stegeman had also used the alias Frank Wincheski when he purchased photo-engraving supplies from Inland Photo Supply Company in Spokane. These supplies were later utilized in a counterfeiting operation run by the man who claimed to be Harold Stegeman.

Be he Frank or Harold, Barb's tall, dashing, and debonair beloved was a creative piece of work: a fraudulently obtained United States passport, fabricated identification and driver's license, hundred dollar bills which he had painted in an Idaho shed, and fingerprints matching those of a respectable, albeit deceased, Portland businessman named Phil Champagne.

Barb Stegeman and her five children had two good reasons to be dismayed. First, she was on trial for passing bogus bills. Second, she had been unceremoniously informed that her husband was counterfeit as well.

"Nothing would surprise me now," wept a sorrowful Mrs. Stegeman to an alternately stunned and bemused jury. "My husband could be involved in murder or anything as far as I know."

Richard Sanger, Barb's court-appointed attorney, outlined her defense in simple terms–she didn't know the bills that Harold had given her were counterfeit. Harold was going to testify on her behalf, but the revelation that Harold wasn't Harold didn't make him an ideal witness.

The jury found Barb Stegeman guilty. Released while she awaited sentencing, Barb and Harold were reunited.

"I married a man, not a name," insisted the loyal spouse of Harold Stegeman. Harold, Frank, Pete, and/or Phil wept with joy.

The Secret Service could tell stories about Harold Stegeman to rival the best pulp adventure fiction, but they won't. That's why they're called the Secret Service.

Created in 1865 as part of the Treasury Department, the Secret Service was established to defend the integrity of United States currency. As any amateur anarchist knows, one of the quickest ways to unravel an economy and the government that backs it is to create one's own unauthorized government-issue notes.

Harold Stegeman, however, was not and is not an anarchist, amateur or otherwise, and he will gladly tell stories about the Secret Service, the art of counterfeiting, how to acquire a U.S. passport with fraudulent identification or helpful survival tips for your next shoot-out with international smugglers. He also knows everything about the strange death of Phil Champagne.

Phil Champagne's children, Kathy, Renee, Phillip Jr., and Curtis, wept during the memorial service held in his honor at Portland's Little Chapel in the Chimes. Phil's younger brother, John Robin, was not invited. He had been the last man to speak to Phil alive and his parting words to Phil were these: "I never want to see you again."

"The day didn't start on such an unpleasant note," notes the once deceased Mr. Champagne. "John Robin, Larry Wills, an old high school pal of Mitch's from Boise, Idaho, and I got together for a few days of boating and fishing in the beautiful San Juan Islands. Mitch also invited our buddy, Ed Grass, but at the last minute, both Mitch and Ed had to cancel out."

"John, Mitch, and Phil Champagne were like real brothers to me," recalled Grass. "They are wonderful, kind, hardworking men who always treated me with the most kindness and friendship. I had been with them before on that beautiful forty-two foot Westsail—the Warlock—and I was supposed to be with them that weekend. A family matter came up and I couldn't go, but," said Grass with a sigh, "I often wonder if things would have gone differently if Mitch and I had been with the boys that night."

The boys–Phil, Larry, and John–did not travel together to the San Juans.

"Phil called Thursday to say he was meeting Larry Wills and would like to take him fishing and sailing," recounts John Robin. "I explained I had a prior commitment to take Jim Hinson and his family sailing, but that they would return to Portland on Sunday afternoon."

Saturday, Phil drove up Interstate from Portland through Olympia and Tacoma to meet Larry's Saturday flight from Boise at Sea-Tac International. Arriving in Anacortes, Washington, the two men rented a room for the night at the Gateway Motel.

The following day, while they waited for John Robin to arrive, Phil and Larry asked the Gateway's owner, Gerald Simon, for permission to re-enter the room to watch a ball game. They promised not to make a mess or cause any trouble. Mr. Simon agreed.

Uniting at the Warlock about an hour after the Hinsons had left, the three men had drinks at The Harbor, a little restaurant on the right side of Main Street going into town.

"Then we picked up a pizza from another place on the same side of the street," continues John Robin. "They didn't serve any beer or wine, so we went back to the boat to eat the pizza and go to bed."

The next day, after an early breakfast, Larry Wills bought seasick pills in preparation for their afternoon fishing excursions to Cypress Island. Larry didn't get sick, and they caught one sand shark and one small cod.

By nightfall, the hot August day, augmented by chips and beer, had cooled to balmy island warmth. Phil, Larry, and John Robin returned to Anacortes and tied up in front of Boomer's Landing next to Wyman's Marina overlooking Guemes Channel.

"Phil fell when jumping from the boat to the dock because of his street shoes. I repeatedly tried to get him to wear a pair of my deck shoes," insists John Robin, "but they were a little small for him, so he wouldn't wear them."

Seated in the terraced dining room of Boomer's Landing, the men dined on steaks, chicken, pasta, and salad. Phil and Larry consumed impressive amounts of alcohol while John Robin stayed sober and flirted with cocktail server Linda Carlson. He did his best to convince her of the potential benefits of joining them aboard the Warlock. Having heard similar pitches and being a married woman, she simply waved good-bye as the three men motored out into the darkness.

Once they returned to the boat, John Robin switched fuel tanks and bled the engine. The winds were light, but he raised the sail to help steady the boat and increase fuel economy. Aboard the Warlock, Phil and Larry, over John's objections, began drinking vodka.

"I was a bit drunk, and I know Larry was also. It was a very relaxing day, and I had a marvelous time," relates Champagne, squinting into the horizon as if seeing 1982's San Juan Islands' sunlight dancing and sparkling on the waves. "I enjoyed John, Larry, the weather, the food, the drink. It was the first time I'd had any fun in a long while.

"My wife Joanne and I, after twenty-eight years, had hit significant skids in our relationship. Hell, we had been sliding toward separation for some time. We would have done it sooner, but a promise is a promise, and I take promises seriously. We waited 'til the kids were grown."

Attorney Don Robertson, a silver-haired Mount Rushmore of a man who at one time or another has represented almost every member of the Champagne family, describes Joanne Champagne as "a good mother and hardworking woman. She has always been more conservative and down-to-earth than Phil. Perhaps you would call her old-fashioned, more straight-laced. Some might consider her not as refined as Phil or say that they were a mismatched couple or that she is not the type of woman you would imagine to be Phil Champagne's wife. It is true that they had problems, but I have a great deal of respect and affection for Joanne Champagne."

Others are less generous in their appraisal of Phil's ex-better half.

"She was always unpredictable in her responses to situations," observes John Robin, "you never knew what to expect. She could be perfectly sweet and happy one minute and screaming the next. Maybe there was a medical explanation, but it seemed to me that her mood swings were dramatic and intense."

Then again, maybe Phil made her crazy.

"I had seen her verbally abuse him and insult him in public," recalled John Robin, "but because I was so happily married at the time, I couldn't relate to Phil's unhappiness in the relationship. As my brother has never been perfect, I'm sure she had complaints about him, too."

The children were not unaware of their mother's darker side.

"My kids all love their mother very much and would do anything to protect her, but they all know that she can be verbally abusive and say things that cut like a knife. Even they had to be careful not to talk too much because she would get paranoid and accuse them of conspiring against her."

A few years before the boating accident, Phil confided to his daughter Renee that he wanted to leave Joanne and begin a new life. The idea was not greeted with enthusiasm.

"She told me that all the kids would hate me forever," said Champagne, "and I am sure they were concerned about what would happen to Joanne if I left."

The Champagne household was never the scene of physical abuse or domestic violence. The backlog of emotional bruises from decades of acerbic tirades resulted only in emotional distance and barren stretches of icy silence.

In June 1980, Phil moved out of the family home at 19202 S.E. Bel-Air in Clackamas, Oregon, and rented a small apartment in Gresham about ten miles east of the city limits of Portland. After the split, Phil began killing time and assassinating his sensibilities in Portland's nightspots.

Downshifting from his usual higher class haunts of the Gresham Golf Course, the Cattle Company, Top of the Cosmos, and the Rusty Pelican to some of the metro area's tougher night spots, he exchanged exaggerated and semi-fictional adventure stories with the rough and tumble of diverse locales and questionable people.

Having seldom walked on the wild side since his restless youth, Phil circled these new acquaintances, as would an entomologist approaching new species of scorpion. Half-lit in the dank glow of piratical rum, acting out against the wine-stained backdrop of false front camaraderie, the shiftless, daring-eyes piranhas appeared benignly picaresque.

By the time the music stopped and the bars closed down, Phil had returned to his rented digs. Unlike the wagering braggarts who provided his evening entertainment, Phil had a real job, reliable income, young adults who called him Dad, and friends in high places. What Phil Champagne shared with these unkempt nocturnals was self-induced internal numbness and the sensation of being buried alive by the future.

Phil's attraction to the sizzled denizens of Portland's soggy underworld was not a desire to be part of them, but to be disconnected from himself. In truth, he saw them for what they were—arrested adolescents delaying the detention of adulthood. At fifty-two, Phil had begun serving the life sentence of assumed maturity long ago.

Working in construction, living in constriction, Phil Champagne appreciated any inference of escape. One night, with deadpanned seriousness, he dutifully wrote down the phone numbers given which offered Phil a possible connection to a man in Mexico.

"The more Jim Beam this guy consumed, the better friend I became," laughed Phil. "I let down my guard, and it slipped that I would just as soon start a new life, not that I had any plans to do so, and he said, 'I know a man in Mexico who would probably be happy to have a man like you working for him.'"

The contact was someone who could use a fellow of Phil's talents and maturity in what sounded to be, at best, a dubious import/export enterprise. Phil did not intend to pursue the recommendation, but it tickled him to know he possessed private phone numbers radiating an aura of successful illegality.

"We didn't know each other that well, but as we had been introduced socially through this character's attorney, a lawyer with whom we both conducted perfectly legal and respectable business, he must have thought I was a real good ol' boy."

The man making the referral fell into the social strata best described as "smudged-collar worker"—white-collar appearance, but with dirt underneath more than his nails. He pretended not to be surprised when Phil asked, "What's the number?"

Champagne took down the area code and particulars on the back of a napkin, stuffed it into his inside pocket for later disposal, and changed the topic.

Three days later, when Phil Champagne pulled the crumpled napkin out of his pocket, he hesitated before tossing it in the trash. "What the hell," Phil thought, and copied the numbers into his address book.

"I can't say why I did it. Maybe it gave me a cheap ego thrill to know I had this guy's number."

The episode held sufficient significance for Champagne to share it with his buddy, Alias Mike.

Alias Mike is an alias for damn good reasons. The story of Phil Champagne began with his early and unexpected death, but over the years of his absence, the body count rose.

"Mike said I should have flushed the napkin down the sewer before I left the bar."

Mike was right.

As usual, he understood Phil's mental condition. The two men had shared an unspoken psychic symmetry since their prepubescent bonding as seventh-grade classmates in Lake Forest Park, a once rural community north of Seattle.

In April 1946, when fifteen-year-old Phil lied about his age to join the Merchant Marines, Alias Mike was right there with him. So was their school chum, John LeGate, and John LeGate had a younger sister named Joanne. Joanne had no intention of joining the Merchant Marines, but Phil had every intention of joining Joanne.

"My, oh my," said Champagne with a smile, "I thought little Joanne LeGate was a knockout."

Joanne waved good-bye when Phil, Mike, and her brother John shipped out for Europe aboard the Marine Dragon in 1946. A year later Phil found himself aboard Foss Tug LT377 heading for Honolulu to bring back postwar explosives, and on November 8, 1949, Phil Champagne married Joanne LeGate in a simple ceremony at a preacher's house in Ridgecrest, Washington.

"Joanne was a beautiful bride and," he adds with a hint of impishness, "she was only a little bit pregnant."

Having returned to their old stomping grounds, Phil and his new brother-in-law's stomping quickly got out of hand. On November 27, 1950, the hell-raising, twenty-year-old boys went on a late-night spree, upending tombstones and breaking windows. The King County authorities were not amused. Le Gate and Champagne were apprehended, fingerprinted, and charged with property damage. They were ordered to make restitution and donate one hundred dollars to Orthopedic Hospital.

It was agreed that it would be best if the boys shipped out. Phil finished out 1950 working in Washington's Christmas tree harvest, and in 1951, he and John LeGate sailed aboard the General Greeley through the Panama Canal to New York City. As advised, they took a long, leisurely train ride from the East Coast back to the state of Washington.

And like The Cat in the Hat, the boys came back. Phil Champagne returned as restless, rowdy, and charming as when he was fifteen, with an emphasis on restless and rowdy, the natural consequences of Phil Champagne's haphazard upbringing.

Born in Seattle, the product of the stormy union of Eli and Anita Champagne, Phil's parents were separated at the time of his birth. Fourteen years later, Eli and Anita were officially divorced. Phil and his brothers were raised in poverty, relied on welfare grants for support, and constantly shifted from one home to another.

Anita Champagne and her middle son did not exemplify the finer points of family unity, and fifteen-year-old Phil was referred to the Seattle Guidance Clinic in 1945 because of problems with his mother. With her blessing, he joined the Merchant Marines in an attempt to jump start adulthood. By the early 1950s, Phil was supposed to be a grownup.

"I was a married man with a family to support, but I behaved like an irresponsible teenager," admitted Champagne. "I hadn't matured a whit. And to prove it, on June 9, 1945, I got drunk and took someone's new car for an extended joyride. When I was done with it, I parked it and walked away. The next morning, when I sobered up, I couldn't find my wallet. I went back to the car to see if I had left it there. It turned out I had left my wallet at the gas station when I bought a buck's worth of gas. The gas station attendant turned it over to the cops, who staked out the car. So, there I was, under arrest."

And guilty as hell.

This time, however, he wasn't a wild teen knocking over tombstones. He was an adult who had been caught taking a motor vehicle without authorization. The wife was furious, the judge was not sympathetic, and Phil was sentenced to one year at the correctional institute in Monroe, Washington.

As far as Joanne was concerned, the time, not to mention the behavior, could not have been worse. Their first child Kathy was only a toddler, and Joanne was pregnant with their second.

"Being sent to Monroe was a life-changing experience," admitted Champagne. "I grew up in a hurry. Renee was born while I was behind bars and that really had an impact on me. It was like slapping me upside the head. You never saw a guy change so fast in your life."

Released from Monroe a model of contrition, a more mature Phil Champagne migrated to Oregon with his family and joined Mitch as an employee of Carnation Dairy.

"Phil was one amazing milkman," laughs John Robin, implying that Phil's delivery route was an unending symphony of rattling bottles and squeaking bedsprings.

Becoming a licensed pasteurizer, Phil devoted ten good years to Arden Farms before following John Robin into construction.

Phil built homes while he and Joanne expanded their family. After four children and nearly three decades of marriage, the family painfully collapsed as the housing market did the same.

In 1982, Phil Champagne was no longer a teenager. He was over fifty, his unrelenting optimism and self-confidence were beginning to ebb, and his friends were concerned.

"It was easy to see that Phil was becoming increasingly stressed out and needed a few fun-filled days of fishing, sunshine, and friendship," Ed Grass said, "and we all hoped that the late August trip to the San Juans would do the trick."

The trick was not what anyone expected.

"When we started slicing through the night water, I felt like a free man," said Champagne wistfully. "There we were, a little tipsy, out on the water. I don't remember our destination, but we were near the Straits of Juan de Fuca. I had sneaked another bottle of vodka on board and was still drinking. John Robin didn't like folks getting drunk on the boat, but I didn't get much of a chance to cut loose and have a good time. So what if Larry and I got a little drunk?"

Even the most pleasant evening, fermented in enough alcohol, will turn sour. Old-timers have a name for it: The Darker Drink—the one shot that puts the pall of death on a lively night, turns fellowship into fistfights, loosens petty demons stuck in men's craws, and sets brother against brother.

"Somehow we got on the subject of Mitch's latest construction project—the Cottonwood Condominium development in a Portland suburb. There had been severe cost overruns because of some drainage problems, which we had not anticipated. I was the one to oversee the site, so, according to John, it was my oversight." Phil pauses for a moment of reflection. "It was a stupid discussion for two brothers, one of them rather tipsy, to be having in front of a friend on a boat in the dark of night. Had Mitch been there, he would have told us both to shut up."

Phil peered blearily at John Robin through the dark, weaving in rhythm with the rocking boat.

"You're trying to make Mitch's problems all my fault," declared Phil with the conviction of a man inebriated. "Don't blame me for things I can't control."

Blame is important to drunks and lawyers.

"The last thing I remember John saying," recalled Phil, "is that he didn't want to see me again. He turned and started to go either below or to the wheel. He stopped and turned back to look at me."

"D'ya know what?" John, despite his sobriety, let the Darker Drink speak. "If the truth were known, I don't think any of the others in the family want to see you again either."

John certainly knew how to put a positive cap on a night of carefree camaraderie.

"I did tend to criticize Phil," acknowledged John Rubin, "but I don't recall my recriminations being that severe. I usually knew just how far I could push Phil before he got mad or hurt, because Phil was very easygoing and slow to anger. Quite often, my fault-finding would do him some good. We did have that conversation, and I did say those things, but I think that the alcohol amplified the intensity with which he experienced it. If he'd taken my repeated insistence that he put on deck shoes as seriously as he took my remarks about his role in the construction site problems, he might not have gone over the side."

Phil, sizzled, silent, and still in his street shoes, turned toward the stern. He really didn't know where he was going.

He went overboard.

When John Robin caught the brief blur of Phil falling, he wasn't immediately concerned.

"My initial reaction was, 'Well, that's going to wake his ass up, hitting that cold water.' I stopped the boat, turned it around, and thought I would be able to see him right away."

He didn't.

John Robin grabbed a handheld searchlight and jumped down from the wheel, still confident that he would see Phil at any moment.

"I couldn't see him anywhere. I had a life ring on the back of the boat and a strobe light. I took the damn life ring, attached the strobe light, turned it on, and dropped it in to mark the spot. I was worried about the current and how we were drifting. Then I went below and called the Coast Guard, told them that I had a man overboard, had marked the spot, and that we were circling. It took them between twenty minutes and an hour to show up."

Larry Wills, previously pleasantly inebriated, was transformed into a panic-stricken drunk on deck.

"He was out of it, frantic, and flailing around. I was afraid Larry was going to fall overboard also. But he got a grip on himself in a hurry, and even though he had been drinking heavily, was able to steer. He suggested we shut the engine off and sail whenever possible so we would hear better if Phil was yelling."

The Coast Guard helicopter was aided in its search by the cutter Polar Sea. The search lasted thirteen hours.

Recalling the details of the agonizing night, John Champagne fights back a flood of conflicting emotions.

"I know now that it wasn't real, that he didn't die. But it was real to me then, and real to me every day and every night since it happened. I have relived all of it over and over again, year after year. The fear, the prayers, the grief. I've gone over every detail of that night in my mind a thousand times," laments John Champagne. "What could I have done differently, how could I have saved my brother's life?"

There were several fishing boats in the immediate vicinity, but only one of them displayed interest in the search by assisting the Polar Sea.

"After the first hour," John's voice stalls as the memory constricts his larynx, "I knew that we were only looking for a body."

Even sober, an athletic swimmer can be deceived to death in dark waters, explained the Coast Guard. Rather than relaxing and floating to the surface, the natural inclination is to swim against the resistance toward safety. Phil Champagne, it was speculated, swam down rather than up. In truth, Phil Champagne didn't swim anywhere at all.

"I remember hitting the water, but if I had a near-death experience I was too drunk to remember it. I do recall wondering if this is what it was like for Dad."

Champagne's father, Eli Mitchell Champagne, drowned in Washington's Blue Lake when Phil was in his teens.

"If my life was going to pass before my eyes, I wasn't that interested," quipped Phil. "I have never been a fan of reruns, and it wasn't that great the first time around."

Sometimes men make light of what is most important. Phil didn't see the light; he only saw meaningless humdrum repetition in his ordered, rapidly vanishing life as he sank into wet, relentless darkness.

"What had I ever done that was worth a damn?" What had I accomplished in my life? Nothing, I thought, nothing at all. Get married, have kids, raise kids, get old, get sick, die. Big deal."

No one was about to offer Phil Champagne a counseling job at a hospice, but it was his life, his death, his self-evaluation.

"If I had died, it was no big loss. I felt that what came next must at least be different."

Phil Champagne stared death in the face and found the face of a ten-year-old boy staring back.

"Hey, Mom. The man woke up," the boy said.

Champagne's consciousness resurfaced in a child's bedroom. Phil saw toys and other obvious indications of preadolescence, an odd collection of stuffed animals and posters of popular sports figures. Phil had seen these same things in his own boys' rooms.

When his youngest son, Curtis, turned twenty, he had stopped looking at Daddy with the same eyes. If there was blame to be attached, Phil was no longer drunk enough to attach it.

The child's attractive, forty-something mother appeared briefly in the doorway. She smiled, turned, and walked away. Phil heard her use the phone. He knew it was a phone. He recognized the rotary dial.

"Rotary dial. Rotary dial. The name sounds exactly like what it is," Phil spoke to himself, but his lips didn't move. "If you say 'rotary dial,' there is exactly one click for every letter; it takes the exact amount of time to say 'rotary dial' as it does to dial the zero."

He attempted to sit up.

He failed.

He tried to call out but was not sure if sound escaped his throat. For a moment, he wondered if he was invisible, but then recalled both the child and the woman had seen him. It had seemed a reasonable question when it first occurred to him. Maybe he had the flu. Maybe he was delirious. Maybe he was dead. It was too complicated.

The boy continued to stare at the rumpled man, while the man stared at the ceiling. The kid-sized bed barely contained the long, lanky frame of Phil Champagne. The little boy had never before seen a man sleep with his eyes open. The man must be asleep, the child reasoned, because dead men don't cough, moan, and call out names.

"I see you're back among the living." A cheerful male voice commanded Phil's attention and dominated the room. Champagne blinked, bringing his open eyes into focus. He didn't know the voice, didn't know the face. He didn't have the slightest idea where on earth he was.

"At first we thought you were dead."

Champagne's mind attempted to unravel the intricacies of the situation, but the situation wasn't all that intricate. A bearded, roughhewn man in jeans, Pendleton shirt, and black boots filled the doorway with his broad shoulders. Flipping open a Zippo, the man brought the bluish flame to the Lucky Strike trapped between his lips. Phil, after the first decade or the first puff, whichever came sooner, understood that the smoking bearded man was attempting to make conversation.

"You must be Art," mumbled Phil stupidly.

"Art?" The man in the door with smoke pouring out his nose didn't understand.

"Art of Lost Conversation." Phil hated explaining a joke.

"You're been here almost four days," offered the beard. "When I first found you, I thought you were dead. You know I fished you out of the water, right?"

Oh, yeah, the water. It was starting to come off pause and slip into rewind. Playback and paybacks were imminent.

Reclining beneath a poster of Luke Skywalker, Phil propped himself up on his elbows as if a clear line of sight would encourage his brain to realign as well.

"Why didn't you—?" Phil wasn't sure what he was about to ask.

"Take you to a hospital? Well, there's a reason for that. In fact, a couple of good reasons," the bearded, smoking dragon of the doorway, spit a piece of errant tobacco from the tip of his tongue. "I had fish and plenty of 'em, but I am not exactly authorized to be catchin' 'em, if you understand. I was willing to save your life, but not willing to maybe lose my boat."

"I could have died," Phil said, intending a manly bark but gave out only a weak, watery yelp. "Exactly where am I?"

"Anacortes, Washington, or at least reasonably close to it. We're not that far from town. Here, you might want to take a look at this." Pulling a newspaper from under his arm, the bearded fisherman stepped forward. Champagne looked to where the man pointed. "Seems like folks figure you're dead."

It was hard for Phil to focus his attention, let alone his vision, but he understood without having to read the details.

"You didn't have no wallet. But you're the only missing man I know of that ain't missing in this house, so that's you, right?"

"I need to use the phone. I gotta tell somebody I'm alive," Phil said. His voice bore equal traces of desperation and disorientation.

"No phone here," the beard lied. "Tomorrow you can call from town. Your clothes are dry and so's your money."

Phil had forgotten about the money. He always kept cash in his pocket, figuring it was easier to lose your wallet than your pants.

"We don't steal in this family. Helping ourselves to fish provided by nature is one thing. Lifting a helpless man's cash is another. And we ain't askin' you to give us any of it neither. Just keep it between us that you were ever here."

"Yeah…" Phil wondered if it was a delirium-induced illusion or if he was really having a conversation.

"You look like you're driftin', pal. You sleep some more, and in the morning I'll take you into Anacortes and you can give your people a call or whatever suits you."

Phil leaned back and closed his eyes. "I'll need a shave…"

Whatever additional considerations he was about to voice disappeared in the darkness of exhaustion.