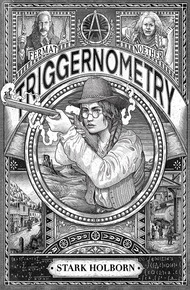

Stark Holborn is a novelist and games writer from Bristol, UK. Stark is the author of the Factus Sequence, the Triggernometry series and the groundbreaking digital serial, Nunslinger. Her fiction has been nominated for the British Fantasy Awards, the BSFA Awards and the New Media Writing Prize.

Stark has written on projects for the BBC, Cartoon Network and Games Workshop. She's currently lead writer on the immersive detective game Shadows of Doubt and a Visiting Lecturer in Interactive Narrative at Glasgow School of Art.

In the Western States, it doesn't pay to count your blessings...

Professor Malago Browne, once the most notorious mathematician in the west, has been trying to leave her outlaw past behind for a quiet life. But all of that changes when her former partner – the deadly and capricious Pierre de Fermat – shows up with a proposition of a lifetime. One last job, one last ride: a heist big enough to escape the tyranny of the Capitol forever.

With a misfit crew of renegade topologists and rebel statisticians, Browne and Fermat prepare to take on the Capitol in the crime of the century. Little do they know the odds are stacked against them…

I love this tale of deadly mathematicians in the wild west from the ever-fecund mind of the mysterious Stark Holborn. I even got to write the introduction to its Spanish edition a while back. Don't miss this one! – Lavie Tidhar

"A wonderful, fresh concept, brilliantly done"

– Joanne Harris, author of The Testament of Loki, The Strawberry Thief, Chocolat & many more"Totally unique… It's like Sergio Leone and William Gibson rewriting the Old West with a quantum calculator"

– Maxim Jakubowski"A wild, rollicking and endlessly-surprising tale of low lives and higher mathematics. I loved it!"

– Lavie Tidhar, award-winning author of By Force Alone, Unholy Land and Central Station"Ascends past its catchy pulp premise, and uses its charming concept to deliver complex characters dealing with murky moral problems."

– Tor.comPrologue: Absolute Deviation

Later, they would call it the Broken Hill Massacre, but to us it was just another job.

We arrived at night, the way we always did, walking so soft even the dogs couldn't hear us. Or perhaps someone had drugged them, poured rotgut into their bowls so they wouldn't holler.

We found the ranch by smell. Cook smoke, singed meat and burnt-bitter corn, urine in the dust close to the building, left by people who didn't want to turn their backs on the vast prairie night.

The ranch house itself was made from sod, crumbling bricks stacked one atop the other. I crept close enough to touch the wall, listening hard. I'd heard the stories; others like us, lured to places like this by promises of work, only to find a mob waiting with ropes and clubs and a prison wagon.

'What the hell is this, Browne?' Ferm hissed, over my shoulder.

'Charity job. Said she needed help. I couldn't say no.'

There was a noise from the darkness, and my hand went to my hip.

'You them?' a woman's voice drifted.

'We're them.' 'Where your horses?'

'Tied to the fence back there.'

'They'll be quiet?'

'Unless someone tries to steal them.'

A beam of light broke the dark open, an oil lantern, smeared with tar to make it secret. It showed us half an inch of face, skin like greasepaper used too many times and a thread of colourless hair.

'This way.'

The light picked out a shed, built against a slope so low that we had to stoop and waddle to get inside. The woman wedged a plank door shut behind us.

''pologise for the secrecy,' she whispered, 'but my boys are in the house. They don't hold with this kind of...' Her lips clapped shut, as she remembered who she was talking to. Instead, she turned the oil lamp up. All around us were potato sacks, tentacled new growth pushing through the hessian. In the middle of them stood a crate, an object resting upon it.

'This it?' I asked.

It was a thick ledger, the cover shrunken, barely able to stretch across the bellyful of pages within.

'Yes. The boys don't know I got it.' The old woman was smiling, the lamplight finding its way between the gaps in her teeth. 'I told 'em I buried it with their Pa.'

I touched the cover. 'May I?'

The woman nodded once, reluctantly, as if I had asked whether I could raise the eyelids of a corpse. The leather creaked. Inside, printed in an old- fashioned hand were the words:

BROKEN HILL RANCH, EXPENSES & ACCOUNTS

Below was the first row of numbers; spiked fours, arched twos, slashes and circles of ones and tens. I turned the pages. Gradually, the columns of sums began to grow sparser, clumsy pencil replacing pen, before stopping altogether.

'My Cuthbert could figure anything,' the woman murmured, 'he could add, subtract, multiply. At the cattle fair once, I even saw him do long division on a man, took the pen right out his hand and wrote down the sum on a playbill, like it were nothing. He were a devil.' Her lips quivered. 'I tried to keep the books up when he went, do the figuring, but I'm no good. And if the boys ever caught me at it–'

'What do you need?' I asked.

The woman's face crumpled with relief. 'I got to figure how many steer we'll need next season, what the harm would be if we were to lose a few on the drive up north. And I need to reckon what profit we might make at the fair in... cash.' She whispered the word as if it were a sin. 'My boys, they got no idea about calculating, you see. They'll take them beasts north and get robbed blind by all that no-good number talk.'

She stopped her mouth, staring at me. I ignored it.

'We'll need ink,' I said.

It was dull work, the type of thing I could have done blindfolded, with my ears plugged and both hands tied behind my back. But it was work, and it felt good to help someone with these simple sums. It certainly made a change from the usual banditry. The sight of those chicken-scratch numbers was a salve after weeks on the run, trying to sleep with one ear pressed to the ground and the bright, cold stars mocking above, taunting me to sleeplessness with coordinates, until my lips moved, murmuring M = E – e sin E and my tears blurred the stars to light.

I looked down at my calculations, the neat balancing of the ranch's books, based on the woman's vague idea of how many steer had been purchased, how much for barbed wire and how many wagonloads of wood. On the other side of the crate, Ferm was working through the ranch's likely profit; he was complicating it unnecessarily by adding in the probability of wolf attacks and a horse going lame, the effect of drought or fire, theft or rustlers... The flamboyance would have made me smile, had it not been for the feverish scratching of his pen, the desperate look in his eyes. It reminded me of what we had been reduced to.

The woman was nodding in the corner. Quietly, I reached into my jacket and brought out a canvas-wrapped bundle. Inside lay the spectacles, bent and scratched and precious. I hooked them over my ears, felt a rush of relief as the muscles around my eyes relaxed, so I could see my workings clearly. It went faster after that, and I wrote the final number in the last column with a sense of deep satisfaction. I knew the feeling would fade even before the ink had dried, but for that moment, I was happy.

'Browne?' Ferm was grinning at me from across the crate, his nose smeared with ink. 'Look at this. Since we're talking about steer, guess what I used for the calculation?'

I blinked at the paper he shoved towards me, trying to fathom his terrible handwriting.

'Tail probability.' His eyes were wet with suppressed glee. '∫TP (x) d x. We're talking about steer. Tails.'

He let out a shriek of laughter, forgetting for an instant that we weren't in some teacher's lounge back east, surrounded by the smell of tobacco and coffee like the old days. It wasn't a loud noise, but in that vast silence it might as well have been gunshot. Even before he could clap a hand to his mouth, the woman had awoken. She motioned for us to stay still. It was so quiet that I could hear her eyelids clicking as she blinked. The paper trembled in Ferm's hand.

'Ma?' a voice called from beyond the door. 'Ma, you out there?'

'Oh Lord,' the woman's face was waxy with sweat; the ledger lay open on the crate, filled with illicit workings. She snatched it to her chest.

'Get out,' she said.

'You haven't paid us.'

'I can't, the money is in the house–'

'Then we'll wait. Go and tell them it is nothing.'

'I...' the woman fumbled with the plank door. As soon as it was open she staggered out, into the night. 'They're in here!' she yelled. 'In here, I got 'em trapped!'

Ferm lunged after her, too late. The darkness beyond was filled with the sound of footsteps, belts jingling, hounds kicked awake. An ambush, after all. Light spilled from the ranch house, and with it came men, all armed, all ready. One stepped in front of the others. The oil light sparked on the star pinned to his chest.

'I hereby arrest the fugitive "Mad" Malago Browne for the crimes of murder, arson, robbery, and acts of pernicious arithmetic against the Capitol States. Also the fugitive Pierre "Polecat" de Fermat, for sundry of the same.' There was a rustle of paper. 'I got a poster. Dead or alive, it says. We can try for alive, but if you pull any filthy tricks, we'll shoot.'

'Bastards!' Ferm yelled.

'It's no more than you deserve,' the old woman called back, her voice quavering. 'Your kind, you're out of control, and if it ain't beaten out of you–'

Fermat didn't let her finish. There was a gunshot, a gasp, then a thud as the ranch ledger hit the dirt, a bullet hole smoking at its centre.

It was all the invitation they needed. The darkness became a mess of gunfire and powder and the hot screech of metal, bullets thudding into the sod walls. They had never intended to take us alive. They only needed our corpses to match up against the posters that emblazoned walls from here to the Capitol.

I looked at Fermat, sheltering on the other side of the doorway, his revolvers drawn, teeth clenched, eyes wild. My own weapon was in my hand. I didn't even remember drawing it. In that thick yellow light, it glinted pure silver. I gave the signal and, as one, we threw ourselves around the door.

+

A week later I heard a newspaperman bawling the story of our escape. He told of how a posse of ten had ridden out to the Broken Hill ranch to collect a pair of prize mathmos, and how not one of them had survived.

Our bounty went up, after that, as much for the deaths as for the message we left, burned into the bloodied dirt of the yard:

EQUALITY FOR ALL