Katrina Archer is the author of dark fantasy The Tree of Souls and YA fantasy Untalented. A former software engineer, she has worked in aerospace, video games, and film, and is a freelance copy editor and publisher of speculative climate fiction magazine Little Blue Marble (littlebluemarble.ca). She also writes spicy contemporary romance under the pen name Saskia Laine.

Katrina's work was a 2016 Library Journal Indie Ebook Awards Honorable Mention (Young Adult). She is an alumna of the Viable Paradise and Paradise Lost writing workshops, and a member of SFWA and Codex Writers.

She can operate almost any vehicle that can't fly, doesn't believe in life without books or chocolate, and together with her spouse, puts up with the antics of a sweet potato and a chaos goblin masquerading as cats.

Connect with her online at katrinarcher.com.

The last eight years have been the warmest on record.

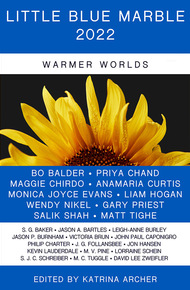

Little Blue Marble magazine's anthology of speculative climate fiction and poetry from an international slate of authors mourns and hopes in equal measure for the fate of our world and its ecosystems.

May these visions of the future inspire collective action before climate chaos becomes irreversible.

"A wonderfully eclectic collection of science fiction and fantasy stories, tied together with the overarching theme of climate change and how humanity can and may deal with it."

– Reader review"Sea Turtles" by Monica Joyce Evans

I don't know how it happened, only one day he was my son and the next he wasn't. It's been a month, and now he's a sea turtle.

He never even liked sea turtles. I don't remember them from his childhood, sea turtles or llamas or little grey owls, all those pastel animals that end up in cribs and bed sheets, behind pillows. The fluffy places that he grew out of.

We sent him to college and two months later they sent him back. Slow, they said, and sluggish. We heard the terms "deferred scholarship" and "nonacademic withdrawal" and "student Access-Ability," which is a pun we think. It all meant: he's not what we thought when we accepted him. Send him back if he changes for the better.

And now he's a sea turtle. Who doesn't need a bachelor's degree in public policy, that's for sure.

Apparently, he volunteered.

He explained it to me once in high school. Sea turtles were going extinct, he said. I know, I told him over sliced oranges and a banana, probably there was cereal too. I know they're going extinct. They've been going extinct since I was a little girl, and that was a long time ago.

I know, Mom, he said, but now it's really happening. Now we have to do something to save them.

Why, I remember asking, pouring coffee into a mug. He'd started drinking coffee, about the same time he grew the thin mustache he wouldn't shave. Maybe his father could talk to him about the mustache, I thought, handing him the mug and meeting his eyes, and that might have been the moment when he decided. Maybe. Because he looked at me like I was an alien thing, with revulsion that I could question the worth of sea turtles.

I mean, I said—floundering at this large, male creature that was my son, that had been such a small bundle years ago—I mean, isn't it sort of a natural thing? Not that it's a good thing, but it happens, you know.

Nothing is natural anymore, he said.

The last time I saw my son, before he was a sea turtle, I don't remember what I said to him. I feel like I should. We'd had a nice day, a nice lunch, just a boy and his mother, somewhere close to a college campus. A different college, one we thought he should consider, maybe. Closer to home. I had an errand to run, new sheets or something, and we took some time out of his day to catch up. He'd become guarded by then. Friendly, warm enough, but everything we talked about was surface water, smooth and shining. Nothing beneath the surface, not that he would let me see.

I mean, I had no idea anything was wrong. I thought that things were getting better.

And I don't remember the last thing I said to him. It was probably goodbye, or I love you, or I'll see you soon.

I hope it was I love you.

Sea turtles, I've learned since, are not good mothers. None of them. There were seven kinds, and now there are four, and they all have names like leatherback and hatchback and green beak something. They lay their eggs in the sand, and when it's warmer, more of them hatch as girls. "And that's the problem," my son had told me, maybe on that last day. "There's nothing but girls out there now. One generation, and then no more sea turtles." And he stabbed at his lunch like it made him angry.

There's nothing anybody could have done, though, I said. I mean, you can't just make the sea colder.

"Can't we?" he said. He was so angry about big things, global things. Not things that should have mattered to him. He should have been a kid still, I thought, worried about classes and girls, or boys. I think I changed the subject.

But we were never anything but supportive of his choices. Even when he left school, even when he made friends we didn't like, all these bright-eyed, intense people. Even when he took medication, or didn't take medication. He was my son. What else was I supposed to do?

The last time I saw him, he gave no warning at all.

I go down to the beaches now. More often than you might think. The weather is nice sometimes, and the sand feels good on my toes. There are no sea turtles near where we live, and I don't think there ever will be again. But I get pictures from him sometimes. When they set him up—stripped him truly naked, nothing more than a brain and a stem, and put his body away, and stuck him in that big male turtle—when they did that, they gave him all sorts of things, tracking devices. Cameras. He doesn't text, but he sends me pictures when he can.

I don't understand them. They're just blue, or maybe green, and wavy. Sometimes with bits that might be plastic, might be something else. Most don't look like anything at all. I suppose he's out there fertilizing eggs, making more sea turtles, and it's not the same as getting married, but he's my son.

Anyway, I spend a lot of time at the beach. Looking out into the waves, wondering if he's ever come up on these shores. Wondering what kind of life my son has now, who can't call home but sends pictures of blue water and plastic and undersea concerns. I look at them, the pictures, the images, standing there barefoot on the beach, and when it gets too dark to see, I go home.