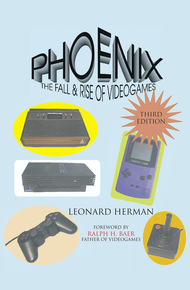

Herman, "The Game Scholar", fell in love with videogames the first time he played Pong at a local bowling alley in 1972. He began collecting videogames in 1979 after he purchased his first Atari VCS and then began writing his first book on videogames: ABC To The VCS, which wouldn't be published until 1996. A programmer and technical writer by trade, Mr. Herman founded Rolenta Press in 1994 to publish his book, Phoenix: The Fall & Rise of Videogames, the first serious book on videogame history. In 2008, Game Informer named Phoenix the #2 book on videogames in all time. The title has been referred as the "Bible of the videogame industry".

Mr. Herman has written videogame-related articles for Electronic Gaming Monthly, Videogaming Illustrated, Official US Playstation, Games, Edge, Pocket Games, Classic Gamer Magazine, Manci Games, Video Game Collector, and Gamespot, as well as editing Video Game Trader magazine.

From Spacewar on mainframe computers to Tetris on pocket organizers, Phoenix has been called the definitive book concerning the history of videogames. Within its pages you'll find the Atari Pong, the Microsoft Xbox 360, and everything in between. But this book goes beyond the complete history of videogames. You'll see how the videogame industry reigned, collapsed and returned even stronger than before. It's all here in Phoenix: The Fall & Rise of Videogames.

"The original bible of videogame history…..there's more raw historical data here than in any book, before or since."

-Next Generation"A meticulously detailed system-by-system record of the history of videogames."

-Electronic Gaming Monthly"Herman has done an outstanding job in making his already excellent book even better."

-Tim Ferrante, Gameroom"Phoenix is still the first place to start in any study of gaming history."

-Game Informer"All in all, this is one of the most fascinating books ever written on the subject."

-Kris Randazzo, Jersey City Video Games ExaminerIn 1984, Nintendo had sold 2.5 million Famicoms in Japan and 15 million cartridges. Despite the prophecies of doom that it received, Nintendo believed that it could achieve those numbers in the United States also. At the Winter CES in January, Nintendo officially announced its plans to market the machine in the United States and Canada.

The Nintendo Advanced Video System (NAVS) seemed to be a step up from the American systems that practically couldn’t even be given away anymore. While those machines had the capacity for 16 colors, the NAVS was able to generate 52 colors. This allowed for realistic 3D graphics.

The NAVS was totally wireless. Its controllers would use infrared light to send signals to the console. The controllers were also different in another respect. Instead of the popular joystick, the NAVS’ rectangular shaped controller featured a touchpad that could move in one of eight directions. It was similar to the disc on the Intellivision’s controllers but more precise. The controller also had two buttons for game starts and resets. A light gun was also going to be sold with the unit for target games such as Hogan’s Alley and Duck Hunt.

Nintendo also announced a 3-octave music board that would be available optionally. Unlike Mattel’s music keyboard that only operated with the Intellivision computer, Nintendo’s keyboard could also function by itself without the console since it used batteries and had its own built-in speaker.

Like all the other companies that had released consoles since Mattel first announced the Intellivision, Nintendo promised a keyboard to upgrade the new console to a computer. It also planned a Game Basic cartridge so players could design their own games from scratch. For those who weren’t creative enough to do this, Nintendo also planned an "Edit Series" of full action games that players would have the ability to modify (but not save).

Since a videogame console is only as good as its available software, Nintendo unveiled 25 cartridges at the CES. The large library consisted of many sports games such as Baseball and Tennis as well as arcade classics from the Nintendo catalog like Donkey Kong.

Despite the fact that videogames were selling so poorly everywhere, Nintendo received a lot of attention at the CES. That was good because most of the people who attended the CES were retailers who were out to purchase new items for their stores. Nintendo told these shopkeepers that the NAVS would be available by the late spring. By the time of the Summer CES in June, the Nintendo game console still hadn’t been released. Nintendo still had a booth at the show and its game console had some new features. Among them was a new name. Instead of the Nintendo Advanced Video System, it became the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). A new release date of late summer had been announced and the initial number of cartridges had dropped to twenty.

Although the music keyboard had disappeared, Nintendo displayed a new peripheral; a ten-inch high robot called R.O.B. for Robotic Operating Buddy. R.O.B. was similar to Androbot’s never released Androman. The Nintendo robot had the ability to assume sixty different positions as it responded to on-screen actions. Like the controllers, the robot was completely wireless.

R.O.B.'s. purpose was strictly to be a Trojan Horse. Since electronic retailers didn't want anything to do with videogame systems, Nintendo needed an angle to get its console into toy stores. R.O.B. was just the angle. Nintendo promoted R.O.B. as a toy. The console itself was incidental and just needed to operate R.O.B. Once Nintendo got the NES into toy stores it didn't plan on doing much with R.O.B.. Two games that utilized the robot were designed and four more were planned to be released by the end of the year. However Nintendo was certain that once people purchased the NES they would be hooked on its games and not its novelty robot.

Summer came and went without the appearance of the NES in any stores. Finally Nintendo announced that the console would be available in mid-October but only in the New York Metropolitan area. The national release of the NES was rescheduled for February 1986. For $159, the console would come with two controllers, the Zapper light gun, the game Duck Hunt, R.O.B., and a game called Gyromite that used gyroscopes and R.O.B.

The release of the NES didn’t send shivers down the spines of the other videogame manufacturers especially because there really weren’t any left. Atari seemed to be out of the running since its new owner, Jack Tramiel, announced that he wanted his company to be a dominant force in the computer industry. As far as he was concerned videogames were dead and the future belonged to computers. Atari’s future was questionable, however. In April, the company announced that it wouldn’t attend the Summer CES. Atari appeared to be experiencing very heavy financial problems and industry watchers began wondering if the company would be able to produce the inexpensive 16-bit computers that it had promised. Atari did manage to ship small quantities of its new 130XE computer; an eight bit 128K that was the descendent of the old Atari 800 computer. Meanwhile, the company experienced more layoffs and the employees who remained discovered a 5-20% decrease in their paychecks.

During the same month, Coleco finally announced what everybody had been expecting for several months, the death of the Adam. However, the company did Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) promise to continue developing software for both the Adam and the Colecovision. It proved this by releasing several new cartridges including Jeopardy and Dragon’s Lair; the latter being the home version of the laser disc arcade game that Coleco had paid $2 million for. Since the game was released on a standard cartridge, the speculation that Coleco might be coming out with a laser disc interface for the Colecovision died.

Coleco’s future involvement in electronics was questionable, however. The only thing that had kept the company from declaring bankruptcy after pouring millions of dollars into Adam was the unprecedented success that it had with its Cabbage Patch Dolls during the preceding Christmas holidays.

The final videogame company was Intellivision Inc., which changed its name to INTV Corporation. By the beginning of 1985 the new company hadn’t yet shipped anything and this led to speculation that it had gone out of business. However, when the American videogame business seemed completely dead, INTV finally began to stir.

In October, the company announced the INTV System III, a brand new Intellivision console. Priced at $59.95, the console was to feature enhanced graphics and was to be compatible with all of the existing Intellivision software. INTV Corp. also planned to release all of the classic Intellivision titles at prices between $9.95 and $19.95 each. In the works was a mammoth advertising campaign in order to revitalize the stagnating interest in videogames.

Activision also believed that there was still a market in videogame software and in the summer it released two new cartridges for the 2600. However these two games, Cosmic Commuter and Ghostbusters, didn’t receive any advertising at all and had limited distribution. Activision clearly had not intended on reclaiming its former glory with these two titles.

Despite Nintendo’s and INTV’s belief that the videogame market was still alive and kicking, very few people in the industry shared this optimism. Videogaming’s final knell appeared to ring when the title of Electronic Games magazine was changed to Computer Entertainment in May. The magazine was also given a complete facelift that resulted in a more sophisticated look to appeal to the average computer buyer. Unfortunately it didn’t and the final issue of this pioneering magazine came out in August.