Jeremy Parish has written professionally about video games for two decades, and amateurishly for even longer. Having written for a wide array of publications (including IGN, Electronic Gaming Monthly, Polygon, Official PlayStation Magazine, Retro Gamer, and more), he now splits his time between curating new releases at Limited Run Games and curating the past with the Retronauts podcast and the Video Works YouTube series. He is not, despite slanderous claims online, responsible for the existence of the word "metroidvania", but he does enjoy that style of game very much. Currently he lives in North Carolina with his wife Cat and a fleet of highly tuned classic gaming consoles.

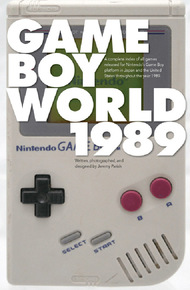

While Nintendo's Game Boy outsold every other game system of the 20th century, historians rarely discuss the system in depth. Game Boy World represents an attempt to archive and analyze the system and its library in depth.

This first volume explores the system, its creators, and every game released for Game Boy in all regions during 1989, the year it debuted. Features in-depth retrospectives for all games, including explorations of the companies and people behind the software, as well as all-new photography of every game's packaging and Super Game Boy color-enhanced screen shots.

A companion piece to the Game Boy World website (www.gameboyworld.com).

"For all its ubiquity, the Game Boy has actually been relatively ignored when it comes to history and design analysis. Luckily, retro game writing all-star Jeremy Parish has created this ode to the Game Boy's first year, specifically converted to Kindle format for this bundle, and it's chock full of exclusive pictures, insights, and details on the genesis of the first breakout handheld game console." – Simon Carless

"Jeremy Parish's meticulous study of the Game Boy's birth catalogs twenty-five software titles from the first year of Nintendo's groundbreaking handheld. While the extensive historic treatments of popular classics like Super Mario Land and Tetris are certainly welcome, Game Boy World 1989 really shines in its exposure of the lesser-known launch titles. Parish makes astute observations on even the most mundane-looking games and paints a wonderful contextualized picture of the advent of handheld gaming. Plentiful box art scans, lovingly captured images, and a clean style tie the whole thing together."

– Jared Petty, IGN"Game Boy World: 1989 is the definitive guide to the first year of the Game Boy's life. While the majority of the text is available on the site, I'm extremely happy to have a physical copy of the book.There's just something inherently wonderful about having a book chronicling the first year of the Game Boy's life on your shelf — a pure, single-purpose entertainment device, that you can take anywhere with no fuss. In that way, the book is kinda like the Game Boy itself."

– Ryan, Nintendo Fun Club Podcast"In depth look at all the Game Boy titles released in 1989. There are beautiful color pictures of the box art, booklet, and cartridges for each game, usually *both* the American and Japanese ones, along with a little review/history lesson on each game. I wish this would be done for every game for every system, to be honest. Being able to see the box art - every angle, too, including the sides, which can be difficult to find for a lot of games - is invaluable enough, but the articles are a treat as well. Easily worth the purchase, highly recommended."

– Amazon ReviewThe Primal Soup

Nintendo has been a major force in the video games industry almost since the beginning, but by and large it hasn't really competed on the same terms as other game makers. The company's history as a toy and gadget maker continues to shape its approach to hardware design, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse. In the case of Game Boy, this mindset definitely worked for the best.

If you look at Game Boy as a game system, its modest power and inferior LCD seem like sheer folly. Taken as a successor to Nintendo's long line of kid-sized gizmos and amusements, though, it makes perfect sense.

And, of course, the man responsible for Game Boy's hardware design,Gunpei Yokoi, had been the mastermind of countless Nintendo doodads and watchamacallits dating back to the 1960s. Former NCL president Hiroshi Yamauchi had catapultedYokoi to prominence when he saw the man messing around with a toy-like device of his own design to kill down time while working on Nintendo's assembly line. Yamauchi promptly commissioned Yokoi to turn the toy into an actual product. He did, and it become one of Nintendo's first commercial hits:The Ultra Hand.

In the years that followed, Yokoi spearheaded the design of dozens of toys, many of which worked as compact electromechanical renditions of arcade amusements. Another major hit for Yokoi came in the form of the Love Tester, a simple toy that measured the electrochemical voltage of two people to "predict" their romantic compatibility. Over time, Nintendo's toy line incorporated more and more electronic elements, which made their mid-'70s entrée into dedicated, single-title game consoles a natural one.

And with their flag planted in the soil of the embryonic games industry, Nintendo's Game & Watch seemed a similarly natural progression: Tiny portable gadgets that repurposed adult-oriented technology (in this case, LCD wristwatches) for kids. And adults, too, but mostly kids.

It's this history that created the primal stew that gave rise to Game Boy. But life didn't come into being until it was jolted by the bolt of lightning that was Sony's Walkman. One of the most revolutionary electronic devices ever made, the Walkman made hi-fi audio portable, packing the ability to play radio and cassette tapes into a compact, battery-powered device that output music through a pair of headphones.

The K-Car Revolution

That was the Walkman's fundamental revolution: It exploded the concept of personal electronics into the mainstream. Sony created a self-contained gadget designed for a single person, compromising top-of-the-line sound for the sake of convenience and portability, and this philosophy influenced hardware design for decades to come.

Nintendo wasn't even shy about borrowing Sony's incredible idea — "Game Boy" reads as an obvious riff on "Walkman," adopting the English-language construction of the cassette player's name while also speaking to its purpose (playing video games) and target audience (boys). Plus, Game Boy made it clear that the handheld was meant as the junior counterpart to the NES — the serious game experience was still to be found on the console, while the handheld offered a less completely formed take.

Game Boy turned NES-era game design into a solitary pursuit… but of course, Nintendo's love of play and socialization still found a place in the system despite its being designed for a single player to hold and play at intimate range. While Game Boy excelled at reproducing NES-like single-player experiences (the first year alone would bring players Super Mario, Castlevania, and Final Fantasy spin-offs), the system could also connect to other Game Boys through its Link Cable feature.

The Link Cable allowed as many as 16players to daisy-chain together… well, at least in theory. In practice, all but a handful of multiplayer games limited themselves to two-person experiences. By no means was this solely a Nintendo innovation, either. Atari's Lynx included a similar feature, the ComLynx, which enabled similar head-to-head play options.

But Link Cable's presence demonstrated Nintendo's priorities — after all, Lynx was meant to be the Cadillac of portable game systems, a massive luxury device with all the bells and whistles. Game Boy was a K Car, compact and inexpensive, its feature set stripped to the bare minimum. Nintendo cut every corner they could, but the ability to socialize made the final cut.