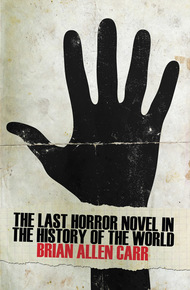

Brian Allen Carr lives in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. His short fiction has appeared in Ninth Letter, Boulevard, McSweeney's Small Chair, Hobart and other publications. His books include The Shape of Every Monster Yet to Come (Lazy Fascist Press), Motherfucking Sharks (Lazy Fascist Press), Short Bus (Texas Review Press), Edie and the Low-Hung Hands (Small Doggies Press), and Vampire Conditions (Holler Presents).

The black magic of bad living only looks hideous to honest eyes.

Welcome to Scrape, Texas, a nowhere town near the Mexican border. Few people ever visit Scrape, and the unlucky ones who live there never seem to escape. They fill their days with fish fries, cheap beer, tobacco, firearms, and sex. But Scrape is about to be invaded by a plague of monsters unlike anything ever seen in the history of the world. First there's La Llorona — the screaming woman in white — and her horde of ghost children. Then come the black, hairy hands. Thousands, millions, scurrying on fingers like spiders or crabs. But the hands are nothing to El Abuelo, a wicked creature with a magical bullwhip, and even El Abuelo don't mean shit when the devil comes to town.

"The Last Horror Novel is quick and strange, its pleasures diverse—from the poetic prose at the beginning, to its riffs on small town life and the horror genre, to the creep out of a swarm of hands. Unlike life in Scrape, it's always exciting. And unlike the citizens of Scrape, it never stays in the same place for too long."

– American Book Review"From the same mind that brought you the delightfully subversive Motherf&%king Sharks comes this cataclysmic novella, which explores how a ragtag group in Scrape, Texas, deals with unnatural and supernatural phenomena, drawing on elements of Mexican folklore, the insularity of small-town life, and the machinations of bodiless hands."

– Barnes & Noble Book Blog"Carr's magic shows in how he handles territory most would strand as genre. He fills the pages with magnetic, mostly sparse language, not far from how Robert Coover's recreations bring new threads to a corpse. His new mythology, set right in the middle of nowhere that many would consider the heartland of our country, is new and old at once, sick and rhapsodic, alive and not afraid to die."

– Vice MagazineThere is a legend, and it varies in telling. Some say it's 500 years old, others, less than 100. It centers on this: a woman is left by a man.

Is it Malinche, Cortez's translator and concubine? Is it a peasant who fell in love over lies? Either way, there are children. Most say two, and most say this: The woman is deceived, destroyed, heartbroken.

The man desires the companionship and matrimony of one closer to his station, one of his own race, nationality.

Once content to confine his time with the mother of his children, the lowly status of her lineage grows troublesome to him, and their current proximity to poverty, while once poetic, romantic, intoxicating in its reality, becomes laborious, repulsive, complicated and terrifying.

Could it be catching, the squalor? If you mix yourself into that cocktail of ill-repute, can you come clean of its contents and rise to your rightful spot in society?

First, there is love.

Let's say the couple occupies themselves in the sunshine of the world, clipping flowers that they dry by hanging upside down in front of open windows—the perfume of their drying, soporific and warm.

There is no music, but alas they are dancing.

Draped in quilts of lavender-dyed cotton, the man and woman read fairytales to their children—cautionary things that expound on the positive results of behaving with virtue, dust-flavored stories where witches drown and spoiled princes are punished.

But it's terrifying to turn your back on your training, and in these moments the man is bungled by internal whispers that revoke his current joys and manifest self-doubt.

The man's protocol, preached to him since birth, is this: Find a woman of strong history, pleasing form and well-postured behaviors, woo her, win her, and have her bear you children. Endow these children with your knowledge. Bless them with your name. Gift them with inheritances. And pray that your line endures strong for eternity.

To the woman chosen, this notion is lost. To her, you seek love. She can't conceive the trepidation mounting in her husband's heart every time her family appears dressed in tattered clothing, playing music on botched instruments with broken strings, drinking until they forget their own language.

She is prideful in the strength of her own charms. She be-lieves the warmth of her affections are celestial-sent, prede-termined by heavens. In her mind and soul, the matrimony she's engaged in is somehow woven into the fabric of the galaxy and her husband's eyes see beyond her flaws because love allows for every kind of forgiveness.

But, this is far from true.

When alone, wandering amongst his own kind, in the town he never invites his family to from fear of humiliation, he encounters myriad women who embody the stock he knew he was supposed to search for. Often, he curses himself for chancing upon his bride, in a world foreign to him, alive with mystery. It is this mystery he accuses, blaming the unfamiliar surroundings as the catalyst for his faulty feelings. The mother of his children is still pleasing to look at, to hold, but now that the magic of her strangeness has tapered, been undone and made homespun, a nausea at the eternity he's promised her has mounted, made him miserable.

It is not so much a plan he hatches as a notion. He leaves himself open to the suggestion that he might still find his way. After all, their wedding did not occur in his church, under his Lord's eyes, but rather near a river at dusk, the faint wisps of orange sunlight leaking like streaks from the horizon.

"If I am approached," he tells himself, "I will not thwart the advances."

In this way he deceives himself into believing that any engagement that might grow out of his openness would be fatalistic, sent by God, and who would he be to intervene?

Maybe he is sharpening a sword, maybe he is cleaning a rifle, maybe he is checking the mailbox—it all depends on when the story occurred. There is nothing definite beyond this: the man finds a more suitable lover.

On a lark, he meets a woman with money from a respectable family, and, because they are more suited to each other, they fall madly in love, and the man sets his designs on stepping away from his former family and into this new lady's life.

He barely explains this to his wife, says merely, "I'll not be home again," and the wife is heartbroken.

Here the legend becomes murkier, splits in two.

Some say the wife does it immediately, some say years transpire before it's done.

This is a possibility: the man's new woman cannot bear him children. They try, over and over, they try, but the results are always the same—nothing happens.

The man knows, for his life's plan to be fulfilled, that he must have children to pass his name to. The new wife knows this as well, lays in blankets weeping and watching the sunset, lighting candles and speaking with Jesus.

It is a great internal debate that twists in the man's soul. On the one hand, he already has two children, on the other, they must stay secret or it could be his undoing.

The new wife's depression does not abate. She stays hunkered down in misery, breaking from her woes only long enough to endeavor to conceive again. Each time becomes more wretched—mechanical sex where no one opens their eyes, and afterwards she sits in odd positions that she's discovered in books, because these unique postures are supposed to aid with conception. They do not.

Long is the season of their sadness, and the man schemes a longshot.

He goes to the new wife in her nest of sorrow.

"Do you love me?" he asks.

"More than anything," she tells him.

"Will you always?" he says. "No matter what?"

She becomes curious. "You know I will," she says. "I don't understand?"

"Promise me," the man says. "No matter what."

"I promise," she says, "no matter what," she says, "I al-ways will."

Then comes the confession along with the scheme, "I can go for them," the man says, "I will bring them here," he says, "they will be our children," he tells her, "yours and mine."

Joy glows in the new wife's eyes. "What are you waiting for?" she asks, and the man goes.

Again the legend leaves us to assume. We know nothing of the specifics beyond this—the man travels to his neglected abode. Perhaps, on seeing his return, the old wife goes wild with hope, "Has he returned? Will he stay forever?"

Imagine then the pendulum of her emotion when he professes his purpose, "I've only come for the children."

She breaks in the ache of those words.

Miraculously, she escapes the ex-husband, grabs up her children, flees with one in each arm.

The man gives chase.

Through brush, thorny trees, barbed grasses and crags, he pursues her to the river bank where the two were united in marriage. There, in that horrible hour, darkness of night upon them like a curse, the moon casting shadows with its pale yellow light, the woman decides that if she cannot have her children, no one can.

She looks at them, one last time. At their eyes, confused. Their cheeks tight with fear. Mouths open, panicked breathing. Children perceive everything. How could it turn to this?

Once

upon a time

cradled and sung to

now . . .

They say that drowning does not hurt, but you wouldn't know by the scene.

The woman clinches a handful of hair, from each child, a fist of hair, and buries their faces in the river.

Wild must be the thoughts. Facedown in the water, screaming for Mommy. But Mommy is there. Mommy is holding you. Mommy is holding you down.

Breathe.

Eventually your body makes you.

Breathe.

There is no option.

It thinks it's doing the right thing.

Pulling the brackish water deep in the lungs.

The flavor of river bottom flooding the senses.

Sometimes bad choices keep lasting forever.